– by Damarise Johnson, Visitor Services/Gallery Associate

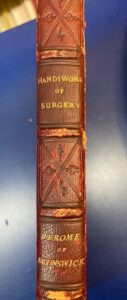

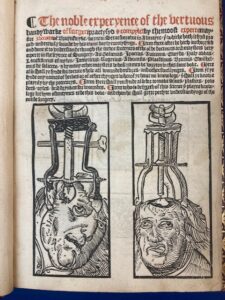

Brunschwig, Hieronymus. The Noble Experyence of the Vertuous Handy Warke of Surgeri. Southwarke, London: Petrus Treueris, 1525.

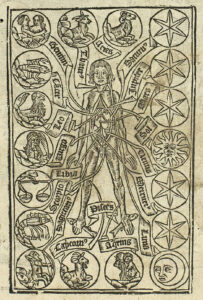

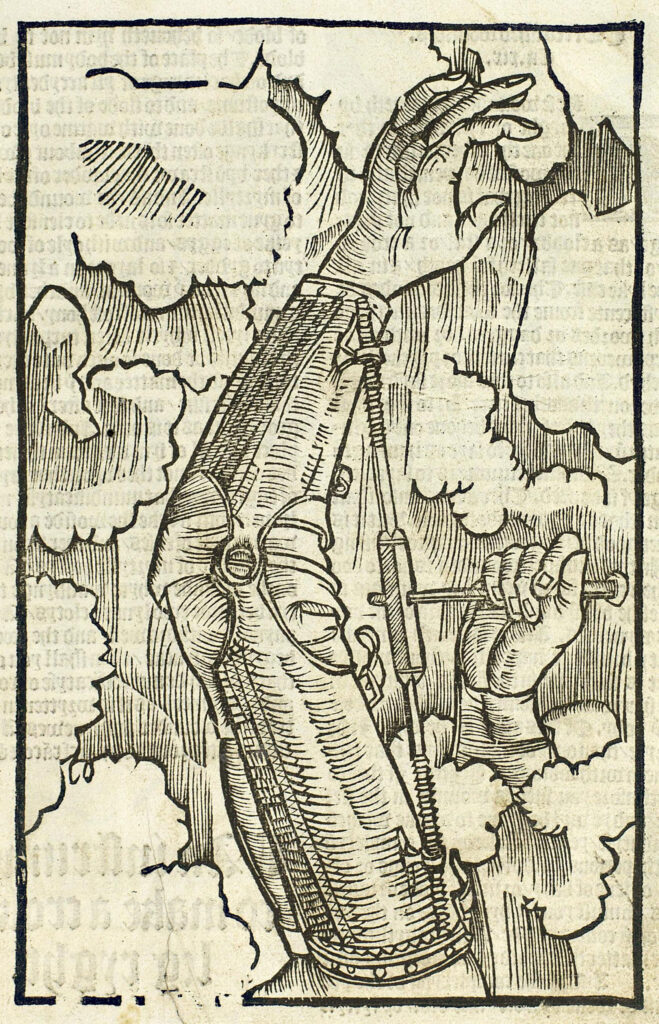

The author, Jerome of Brunswick, was born in 1450 in Strasburg Germany. Brunswick was responsible for writing the first surgery book in English with illustrations. This book was written in the year 1525. It has three sections: Anatomy of the body, Surgery, and Antidotharium, which is based on recipes from plants and minerals. The body section highlights detailed instructions on how to heal fractures, dislocations, wounds, ointments and plasters. Plasters are a kind of sterile bandage or cast, a covering sometimes referred to as dressing the wound. Determining a proper plaster can be very important for a patient’s comfort level.

In this book you will find plasters, powders, oils, herbs and drinks for wounds. People who desire the knowledge of science read this book and better understand the works of noble surgery. Brunswick writes about how it’s best to accept payment only for problems that can be cured as opposed to ones that cannot. He believed doing such a thing maintains a persons good name and reputation, which is especially important for doctors. Brunswick studied under a reputable surgeon, many encouraged him to write a book.

The University Of British Columbia also owns a copy. Its full title is Noble Experience of the Virtuous Handiwork of Surgery.