– by Ashley Lazevnick*

In one of the most influential essays on the artist Georgia O’Keeffe—published in the 1922 issue of Vanity Fair—the art critic Paul Rosenfeld made a vivid comparison between surgical procedures and her creative method:

The painter appears able to move with the utmost composure and awareness amid sensations so intense they are wellnigh insupportable, and so rare and evanescent the mind faints in seeking to hold them; and, here, in the regions of the spirit….[she seems] to sever with the delicacy and swiftness of the great surgeon aplunge in the entrails of a patient.[i]

Rosenfeld was not the only writer to pick up on the surgical qualities of O’Keeffe’s abstract paintings (Fig. 1); among dozens of others, Alexander Brook identified a pointed asepsis in her works that “seem all to be transfixed by an absolutely clean dagger that pierces neatly and hits a vital place.”[ii] And O’Keeffe was just one of several modernists that merited this analogy. Guillaume Apollinaire observed that “Picasso studies an object like a surgeon dissecting a corpse,” while Walter Benjamin characterized the cinematographer as a surgeon, for whom cutting exposed a more trenchant reality than could be achieved by a painter.[iii]

It was this uncanny collection of metaphors that brought me to the Historical Medical Library of The College of Physicians of Philadelphia. What was going on in the history of surgery during this period—I wondered—that would elicit such widespread comparisons between surgical science and the arts? What popular connotations or visual imagery would have informed such critics? Did the specialized literature—though unknown to many of these figures—contradict or enhance the metaphors they used? During my time at the Library, I consulted a wide range of materials, including trade journals, manuals of surgery, and—most stunningly—the collection of medical illustrations done by Hermann Faber and his son, Erwin Faber. It became quickly apparent that the metaphor with which I was dealing was not simply unidirectional; during the same period, surgeons were being thought of as artists—often compared to painters, draftsman, or etchers—while the highly skilled illustrations attested to the enmeshed pursuits of artistic representation, scientific accuracy, and even beauty.[iv]

As it turns out, there were few earth-shattering developments in surgery during the interwar period; this was really more the era of standardization, professionalization, and refinement of techniques. So the core characteristics of the surgical metaphors just cited—composure, control, and dissection—depended upon previous advancements, namely the nineteenth-century’s twinned discoveries of germ theory and anesthetics.[v] Once lauded for his speed and steely courage in removing limbs, the surgeon was now able to make delicate operations with care. At least, that was how the first wave of surgical historians would see it, when they constructed a narrative of triumph: charting the rise of the surgeon from the medieval “barber-surgeon” to the erudite democratic hero. For 19th-century artists, the relatively new incorporation of pathological anatomy into surgery inspired a parallel interest in anatomical dissection, because that method allowed for the disassembly and reconstitution of bodily parts and provided knowledge about the body’s inner-workings that prepared the artist to depict the human figure in a highly convincing manner. This was the epitome of “realism” in the arts and sciences, as exemplified in the paintings of Thomas Eakins. What’s curious about surgical painting in the example of O’Keeffe and her peers, then, is how the metaphor had shed its figurative reference, even while the appeal of science remained: what was surgical about the artist’s technique was her cerebral and analytical procedures.

When comparing artists to surgeons, in other words, critics were tapping into a kind of technical proficiency and a procedural resemblance. In this way, the metaphor was more appropriate than the critics themselves could have anticipated, for Georgia O’Keeffe’s process of creating a picture involved priming her canvas white, selecting a pencil, then a stiff-bristled brush, guiding her instruments across its surface with practiced gestures that she had learned after years of training. A recognized influence on O’Keeffe was Arthur Wesley Dow, the arts educator whose method of isolating and perfecting three principles—line, notan, and color—was inspired by Japanese painting and his friendship with Ernest Fenollosa.[vi] O’Keeffe assiduously studied Dow’s textbook Composition (1899), which begins by recommending the proper tools. No doubt, she followed Dow’s advice for obtaining brushes in a variety of lengths for creating different effects of continuous or broken lines, since she assembled an enormous collection of materials which are today arranged in a manner that visually recalls the layout of scalpels and suturing needles in surgical trade catalogues (Figs. 2-3). Beginning in the late 19th century, instrument companies such as George Tiemann’s had effectively made specialized instruments vastly available to medical professionals. Lush with full-sized illustrations of their products, and sometimes instructions for use, such catalogues document a complex interaction between the fields of surgery, commerce, and graphic art.[vii] Manufactured with stainless steel for the first time in the 1920s, and sold in a number of shapes with a fairly consistent design style, scalpels were among the most versatile instruments.[viii] A deeper historical dive reveals that the designs for “flesh-working” tools had derived from non-medical sources—domestic cutlery, weapons, and butchering implements—making the visual analogy between paintbrush and scalpel (or pencil and scalpel) all the more compelling.[ix]

Once the materials were selected, the method of drawing or painting required perfect bodily form. In Composition, Dow explained how to hold the brush perpendicular to the plane of the drawing so “that it may move freely in all directions much like the etcher’s needle” (Fig. 4):

Steady the hand if necessary by resting the wrist or end of the little finger on the paper. Draw very slowly. Expressive line is not made by mere momentum, but by force of will controlling the hand. By drawing slowly the line can be watched and guided as it grows under the brush point.[x]

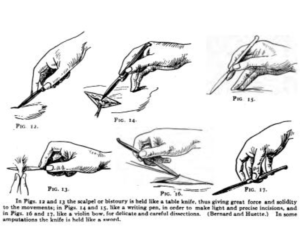

The surgeon similarly began any operations by making incisions that he had practiced for years on cadavers. Francis T. Stewart’s A Manual of Surgery (5th edition, 1921), coaches the student on the specifics, including the variety of ways to hold the scalpel, which could entail holding it like a table knife, pencil, violin bow, or a sword (Fig. 5).[xi] The directions offered by Dow and Stewart, despite several differences, share a common emphasis on control—the slow and deliberate motions of the hand that led to “clean-cut” incisions or an “expressive line.” Thomas Schlich calls this a “repertoire” of gestures (Fig. 6), with the pencil-position of the scalpel participating in a wider trope that linked surgical techniques to penmanship when the pressure of the scalpel needed to be “firm, but light and graceful” (according to one operator).[xii]

To my mind, by extension, it matters less how O’Keeffe held her brush than the fact the she perfected her technique through the studied repetition of gestures shared by both her drawing teacher and the surgical student. Finally, because the surgical profession at this time was dominated by male practitioners—and because the popular image of the surgeon was definitively masculinized—O’Keeffe’s status as a “great surgeon” can be understood as transgressing the gendered binaries that were regularly assigned to both medical and artistic professions.

Arthur Wesley Dow, Composition (1914) 9th edition (New York: Doubleday, Page & Co. [1899] 1914), 17 and 19.

Sources:

[i] Paul Rosenfeld, “The Paintings of Georgia O’Keeffe: The Work of the Young Artist whose canvases are to be exhibited in Bulk for the First Time this Winter,” Vanity Fair, vol. 19 (October 1922): [56, 112, 114] 114.

[ii] Alexander Brook, The Arts, vol. 3 (February 1923), reprinted in Barbara Buhler Lynes, O’Keeffe, Stieglitz and the Critics, 1916-1929 (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1989), 194.

[iii] Guillaume Apollinaire, “On the Subject of Modern Painting,” Les Soirées de Paris (February 1912) quoted in Art in Theory, 1900-2000, An Anthology of Changing Ideas, New Edition ed. Charles Harrison and Paul Wood (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2003), 187). For an excellent account of Benjamin’s use of the metaphor, see Susan Buck-Morss, “Aesthetics and Anaesthetics: Walter Benjamin’s Artwork Essay Reconsidered,” October, Vol. 62 (Autumn 1992): [3-41], 28.

[iv] Thomas Schlich, “‘The Days of Brilliancy are Past’: Skill, Styles and the Changing Rules of Surgical Performance, ca. 1820-1920,” Medical History, vol. 59, no. 3 (2015): [379-403], 393.

[v] Christopher Lawrence, “Democratic, divine and heroic: the history and historiography of surgery” in Medical Theory, Surgical Practice (New York: Routledge, 1992), [1-44] 9-10. I appreciate Christopher Lawrence’s caution that the discovery of anesthetics and antisepsis was not an immediate breakthrough but rather seen as such only after decades of historical retrospection. For a period history of these advancements, see: Morris Fishbein, “The Progress of Medical Science—IV: Serums, Vaccines, Surgery, and the Outlook for Prolonging Life Through Hygiene,” Scientific American (January 1926): 26-7.

[vi] See “Arthur Wesley Dow, Artist and Educator,” in Arthur Wesley Dow and American Arts & Crafts, ed. Nancy E. Green and Jessie Poesch (New York: American Federation of Arts, 1999).

[vii] Claire Jones offers a trenchant study of exactly this collusion in Britain The Medical Trade Catalogue in Britain, 1870-1914 (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2016).

[viii] Kirkup, “The History and Evolution of Surgical Instruments, IV The Surgical Blade: From Finger Nail to Ultrasound,” Annals of Royal College of Surgeons of England (1995): 380-388.

[ix] Francis T. Stewart, A Manual of Surgery: for Students and Physicians, 5th edition (Philadelphia: P. Blakiston’s Son & Co., 1921), 73-75. John Kirkup, “The History and Evolution of Surgical Instruments, (I) Introduction” Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England, vol. 63 (1981): 279-285; “From Flint to Stainless Steel: Observations on Surgical Instrument Composition,” Annals of Royal College of Surgeons of England, vol. 75 (1993): 365-374.

[x] Arthur Wesley Dow, Composition (1914) 9th edition (New York: Doubleday, Page & Co. [1899] 1914), 18-19.

[xi] Francis T. Stewart, A Manual of Surgery: for Students and Physicians, 69.

[xii] Schlich, “‘The Days of Brilliancy are Past,’” 385.

*Ashley Lazevnick, PhD, is the Jane and Morgan Whitney Fellow at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.