Over the past 11 months, we have examined the College’s collection of all things medieval: manuscripts, incunabula bound in manuscript waste, and uncatalogued documents. Features of our medieval materials that I’ve written about include catchwords, ink (here and here), illuminations (here, here, and here), scripts (here, here, here, and here), and parchment. But what’s the point? Why study these books, leaves, and documents that are over 500 years old?

To answer that, I’m going to quote an earlier post of mine, “Making the Medieval Digital”, here:

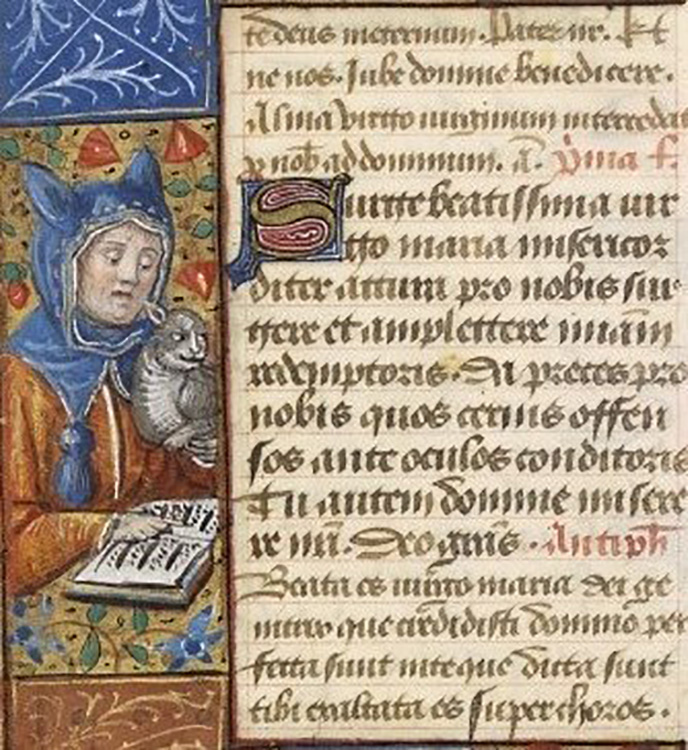

Some medieval manuscripts contain the only copy of a text copied contemporaneously to when it was written. The scripts show readers the evolution of handwriting (the study of handwriting is paleography), just as the dialect or language used helps determine the geographic origin and date of the manuscript. Grotesques and other marginalia reveal the symbolism attributed to animals and what contemporary society thought was important to emphasize (or ignore). Glosses written in by later readers and ownership marks tell the story of manuscript’s use, as do rubbed or crossed out images and text. For those interested in codicology (the study of books as physical objects), medieval manuscripts illustrate early bookbinding techniques, how paper and parchment were made, and the composition of inks. In short, medieval manuscripts can tell us much about what their societies thought, believed, found important, or wanted to dismiss or omit; how items like leather, parchment, paper, and ink were created; and the dissemination of knowledge.

The Library’s manuscripts – surely only a miniscule percentage of those which were written – are all medical in nature; some contain recipes, others translations and/or copies of earlier (often Classical) medical texts. The fact that these survive mean that they were copied in great numbers, or people cared enough about their contents to take special care of the codices. As we’ve learned, texts like the Regimen sanitatis and Bernard de Gordon’s Lilium medicinae were popular with contemporary physicians and philosophers. Constantinus Africanus’ Viaticum is an example of the revitalized flow of knowledge from the East to the West (you can thank the Crusades for that, at least).

Our incunabula bound in manuscripts tell a different, but still important, story. While it’s true the College’s incunabula are treasures in their own right, they don’t get used very often by researchers. Some are rare, while others can be found in various special collections repositories. What makes a few so very special are their manuscript bindings. These bindings tell us what works an early printer or bookbinder felt weren’t important – or perhaps the texts were outdated, or the codex was in poor condition, due to too much neglect or too much devotion to studying the text.

Unlike today, books in the Middle Ages weren’t ubiquitous. They were expensive to produce and buy, and a large amount of the population was not ‘literate,’ so it was more common for the early medieval household not to own one. (For a discussion of what is literacy and a brief history of western European readers, see Martin Lyons, A History of Reading and Writing: In the Western World, 2009.) To me, these facts make it even all the more incredible that we have as many as we do, even those that have been recycled as wrappers and other binding material.

Medieval manuscripts can tell us so much more than what we see at first glance. To make an appointment to study the Library’s medieval manuscripts, please email library@collegeofphysicians.org. If you can’t visit the Library in person, keep an eye on the Bibliotheca Philadelphiensis project page – all ten of our medieval manuscripts have been digitized as part of the project, as well as three of our early modern manuscripts. You can view our digitized manuscripts through the University of Pennyslvania’s OPenn portal.

“A book is a fragile creature, it suffers the wear of time, it fears rodents, the elements and clumsy hands, so the librarian protects the books not only against mankind but also against nature and devotes his life to this war with the forces of oblivion.”

― Umberto Eco, The Name of the Rose