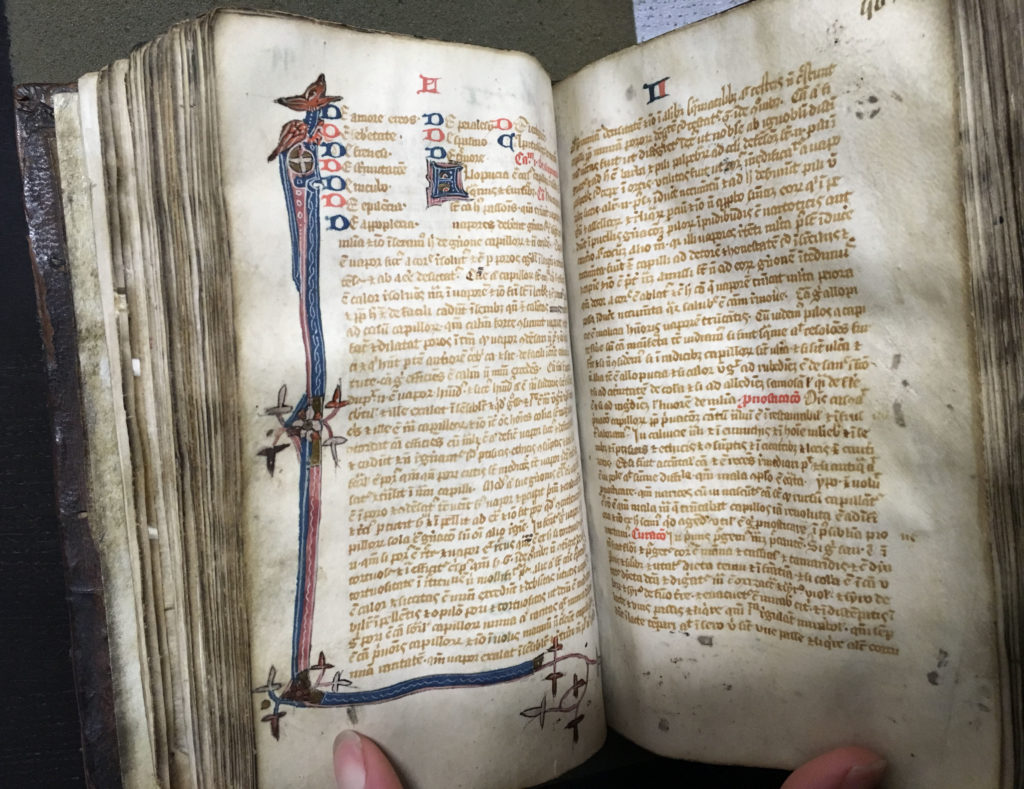

10a 249 is nearly the only illuminated manuscript we have in the Library. As I mentioned last week, 6 out of the 7 original illuminations are still extant. All 6 are initials, and the one pictured below signifies the beginning of Book IV and features 3 human heads.

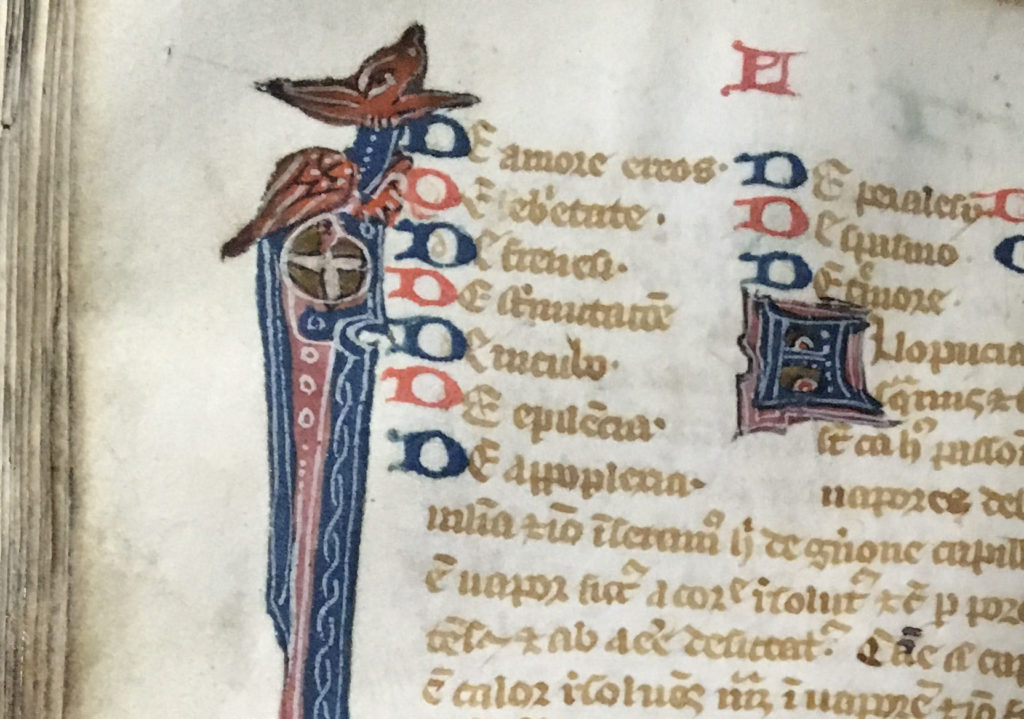

However, my favorite illumination has to be the one at the beginning of Book II. This little beastie (a very technical term) is reminiscent of animals in earlier Anglo-Saxon and Celtic manuscripts – see some examples from the British Library here. While actual bestiaries (books containing descriptions of animals, real and imaginary) were popular during the 12th and 13th centuries, interest seemed to decline during the 14th century, but beasties still found homes in the margins of manuscripts and as illuminated initials. They were often used to symbolize attributes, such as fidelity, promiscuity, or fertility, and Christian morals or allegories.

Another feature of the illuminations in 10a 249 is the distinct shade of pale pink used. Together with the blue and the darker pink, the pale pink is a recognizable element of English manuscripts.

Sources/further reading:

Bahr, Arthur and Alexandra Gillespie. “Medieval English Manuscripts: Form, Aesthetics, and the Literary Text.” The Chaucer Review 47, no. 4 (2013): 346-360.

Bintley, Michael D. J. and Thomas J. T. Williams, ed. Representing Beasts in Early Medieval England and Scandinavia. Woodbridge, Suffolk: The Boydell Press, 2015.

Brown, Michelle P. “Bestiary.” Understanding Illuminated Manuscripts: A Guide to Technical Terms. J. Paul Getty Museum: Malibu and British Library: London, 1994. Courtesy of Michelle Brown and the British Library: https://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/GlossB.asp.