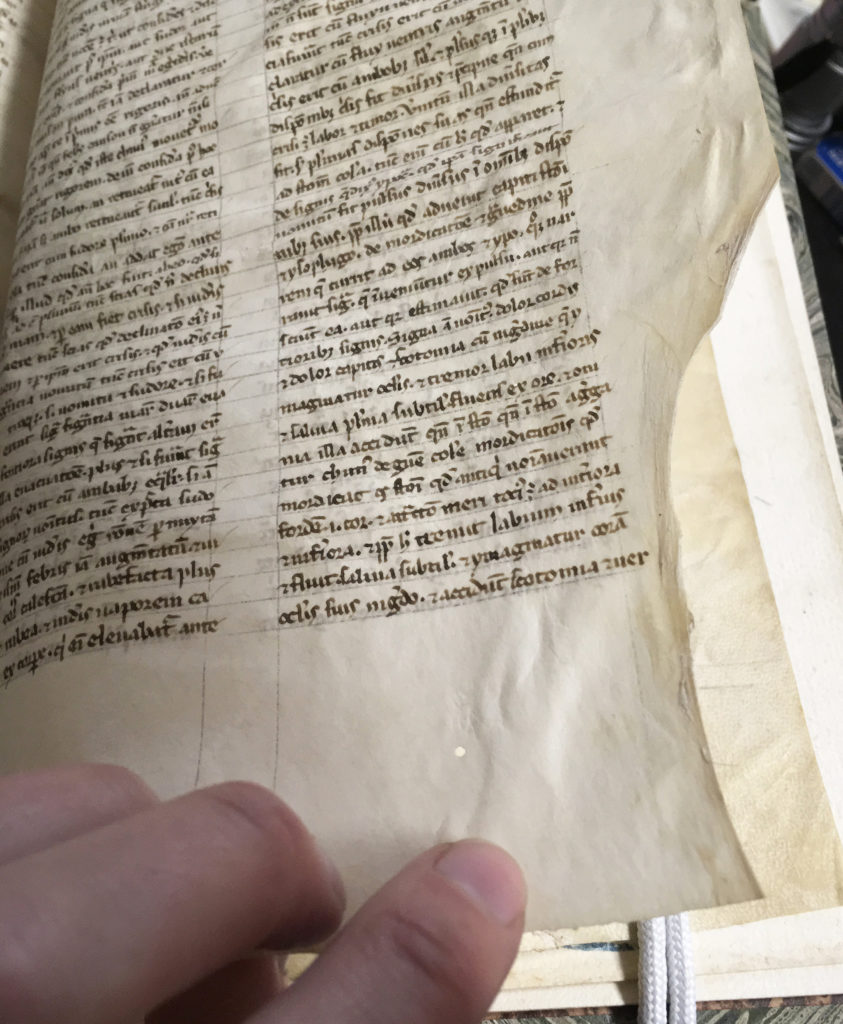

Like the majority of the Library’s medieval manuscripts, 10a 233 is written on parchment (animal skin). It’s not of particularly fine quality, and the difference between the flesh side and the hair side is striking.

Parchment is made by taking animal skins, carefully selected for as few blemishes as possible, and soaking them in lime. The lime helps loosen the roots of the hair. After soaking for several days, the skin is removed from the wash and the hair is scraped off. The skin is then stretched tight on a frame, held up along the edges by small pebbles around which the skin is wrapped and then knotted with ties. The skin is scraped to remove any remaining hairs and flesh using a crescent-shaped knife called a lunellum.

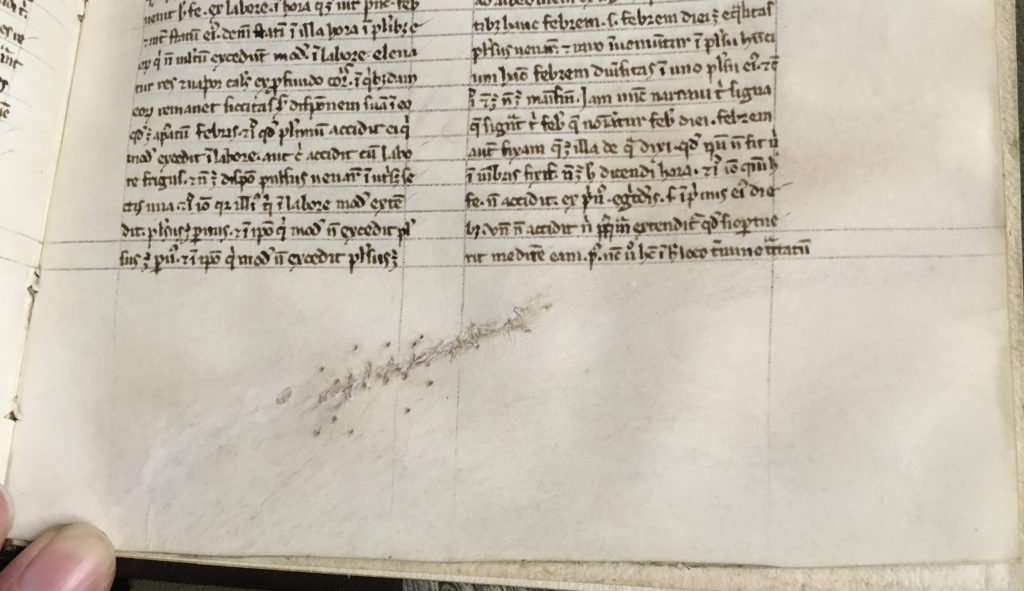

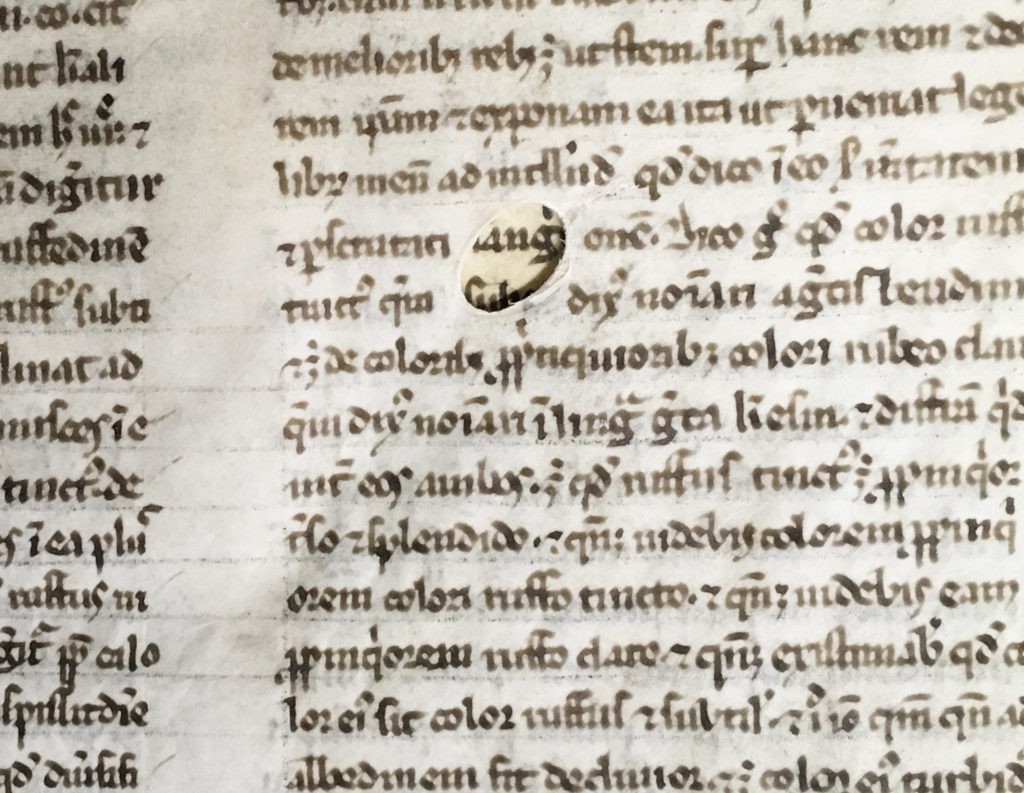

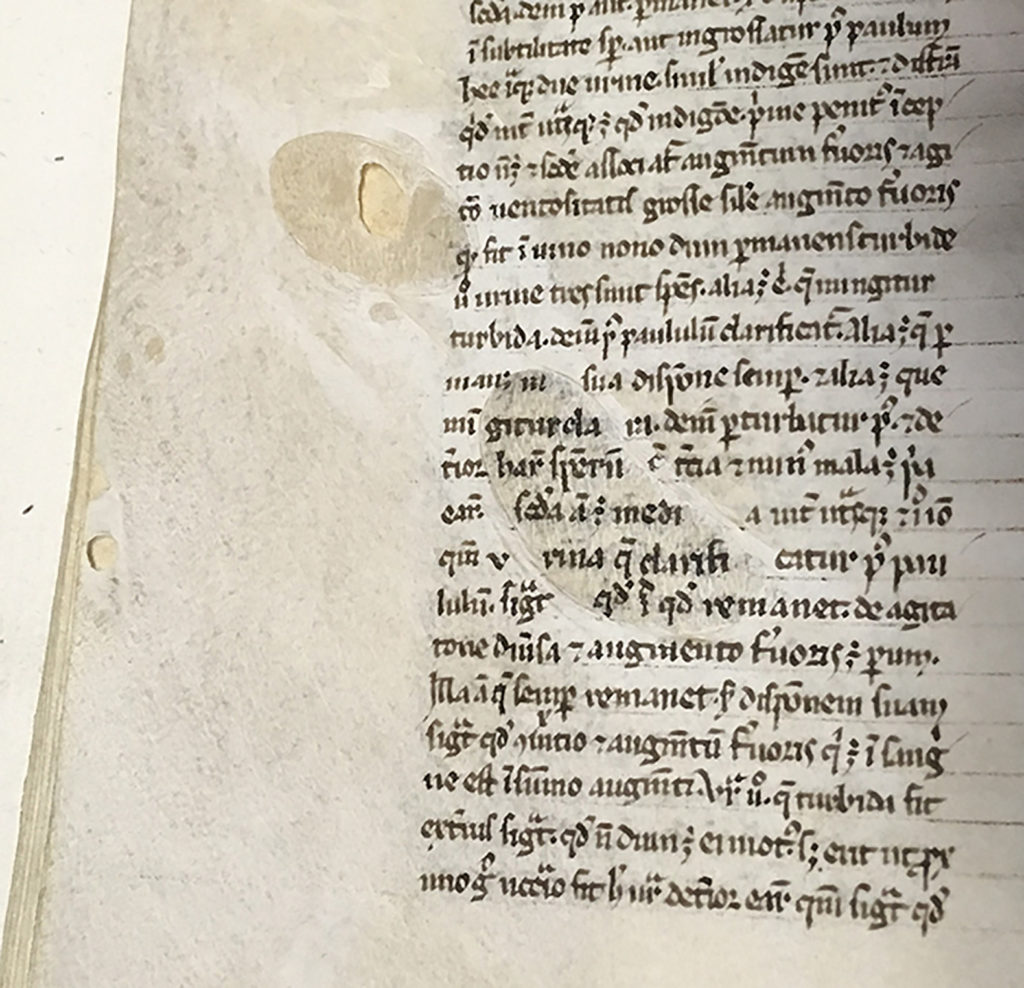

High-quality parchment was scraped very thin, sometimes appearing nearly translucent. Other factors, too, decided the quality of the parchment: existing holes in the skin from scars or fresher wounds (namely bug bites); visible hair follicles; greasiness. Parchment makers needed to ensure they did not scrape the skin too thin, or the parchment would tear.

Holes in parchment sometimes were stitched, sometimes written around, sometimes repaired, and sometimes it worked out so that a hole or the curved edge of the skin became the edge of a folio. 10a 233 has examples of all of these situations.

Sources:

Baranov, Vladimir. “Parchment.” Book Production: Materials and Techniques of Manuscript Production. Medieval Manuscript Manual. Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University. undated.

Baxter, Stephen, presenter; and Andrea Illescas, producer and director. “How Parchment is Made.” Domesday. 2015. London: BBC Two.