– by Wood Institute travel grantee Urmi Engineer Willoughby*

It is difficult to pinpoint the presence of the disease presently called “malaria” in early America because of the inconsistent terminology used by doctors in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

This is partially because the symptoms of malaria, which include fever, headache, chills, muscle aches, nausea, jaundice, vomiting, and general malaise, resembled other common diseases such as yellow fever, typhoid fever, and influenza. For much of the nineteenth century, doctors in Europe and North America referred to the disease using descriptive terms that indicated observed symptoms and environmental factors. The most distinctive features of malaria are its periodicity and alternating of chills and fever, evident in the medical term “intermittent fever,” the more common “fever and ague,” and more specific terms that identified the intervals between attacks of fever (quotidian, tertian, and quartan fever).

Doctors often associated fevers with the natural environment, using terms such as country fever, swamp fever, and marsh fever; they also alluded to seasonal and climatic patterns, using terms such as summer fever, autumnal fever, and estivo-autumnal fever. When combined with vomiting, they sometimes added “bilious” to the description. They further classified fevers according to severity, using terms such as benign and malignant. It is likely that most of these fevers were forms of malaria, caused by Plasmodia parasites and spread by infected Anopheles mosquitoes and humans.

Etymologically, the English word malaria comes from the Italian medical term “mal’aria,” derived from the Latin “mala aria,” which simply means “bad air.” However, by the mid-eighteenth century, Italian physicians used the term to refer to bad airs that they associated with a specific febrile disease that emanated from marshes and swamps in the lowlands of western Italy. Anglophone sources initially used the term in reference to endemic fever in Italy, and it began appearing in medical literature in the 1820s.

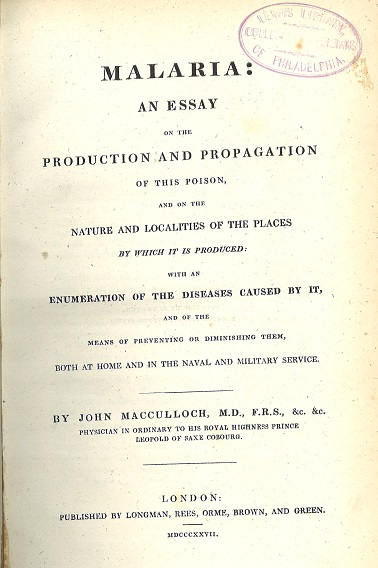

Doctors used the term to refer to a perceived cause of the fever, rather than a specific illness. The earliest known English usage conceptualizes malaria as the causal agent of many different types of fevers and other diseases, and it was most commonly identified with marshes, swamps, and rotting vegetation. The Scottish-trained geologist John MacCulloch (1773-1835), who completed his M.D. at the University of Edinburgh, is credited with introducing the term in Anglophone medical literature.[1] In 1827, he used the capitalized term “Malaria” to refer to a “poison,” which he argued was the cause of several diseases:

This is the unseen, and still unknown, poison to which Italy applies the term that I have borrowed, Malaria. This is the cause of fevers both ordinary and intermitting; but it is the cause also of other disorders, scarcely less important in point of numbers and of mortal power. Such are dysentery and cholera; and yet all these united form but one portion of the enormous mass of disease, of suffering, and of mortality dependent on this single cause.[2]

MacCulloch defined malaria as a singular cause of many symptoms and diseases, which he often associated with wetland environments. While he emphasized the connection between malaria and fevers (intermittent and remittent), he argued that it was also the cause of a long list of ailments including cholera, dysentery, diarrhea, apoplexy, palsy, visceral obstructions, dropsy, worms, ulcers, elephantiasis, and even perhaps pellagra. Additionally, he maintained that malaria was the cause of nervous diseases, including neuralgia and associated symptoms such as sciatica, toothaches, and headaches.

MacCulloch further argued that malaria caused racial degeneration among people who lived in “marshy districts,” explaining that “the residence of successive generations in a district of this nature produces a degeneracy of the races, is amply shown in various parts of France and Italy.” He attributed racial degeneration to symptoms including rickets, jaundice, abdominal fat, and premature aging. He theorized that malaria influenced the moral and physical character of peoples who lived in near wetlands, arguing that it caused “unhappiness, stupidity, and apathy,” as well as deficiencies in female beauty.[3] MacCulloch’s broad conception of malaria influenced medical theories about the cause and prevention of the growing problem of febrile diseases in the US and in the British Empire. In the 1830s, several physicians published texts that echoed and reconsidered the idea of malaria as a general cause of disease and debility.

In the 1830s, medical authorities often used the term “malaria” interchangeably with “miasma” or “miasmata,” a Greek term used to signify polluted or unhealthy air. Malaria became increasingly associated with fevers of all kinds, especially those described as intermittent, remittent, bilious, or fever combined with ague. In 1831, Charles Caldwell (1772-1853) defined malaria as “noxious miasma, from which originate the family of diseases usually known by the denomination of bilious diseases,” and argued that it was the source of plague, yellow fever, and cholera, in addition to remittent and intermittent fevers. He claimed that the miasm or “malaria productive of bilious fever” was the same miasm that caused plague in Asia and Africa and yellow fever in Europe and the Americas, and inferred that it was in fact “the cause of the diseases of hot weather, through all time, by whatever names those maladies may be known.”[4] In 1832, William Aiton explained that the term malaria was used synonymously with marsh poison, miasmata, effluvia, and exhalation.[5] Similarly, Francis Boott (1792-1863) used the term to refer to the root cause of many febrile diseases, including intermittent and remittent fevers, typhus, yellow fever, and bilious yellow fever. In his prize-winning dissertation on intermittent fever in New England, Oliver Wendell Holmes (1809-1894) also used the term to describe the cause of several diseases, including neuralgia. He also specifically noted the relationship between malaria and intermittent fever in New England, which he associated with ponds, marshes, and warm temperatures.

Early nineteenth-century theories about malaria were too broad to conceptualize and define the specific set of diseases caused by Plasmodia parasites now known as malaria. However, they signal a movement in professional medicine in which doctors began to view febrile diseases as a universal feature of global environments, associated with marshes, swamps, and warm temperatures. They advocated a view of disease causation that emphasized similarities between warm, wet environments in Europe, the Americas, Africa, and Asia. For example, MacCulloch emphasized the relationship between wetlands and malaria, and described malaria as a widespread global health problem in warm climates:

How widely Malaria is a cause of death, will be apparent almost on a moment’s consideration, when we recollect, that in all the warmer, and thence more populous, countries, nearly the entire mortality is the produce of fevers, and these fevers the produce of Malaria. I have said elsewhere, that it has been estimated to produce one-half of the entire mortality of the human race; nor do I think that this computation, made by physicians of care and consideration, has been exaggerated.[6]

Since febrile diseases were common in the temperate climates of Europe, New England, and Pennsylvania in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, doctors did not associate them exclusively with tropical climates. Many theorists speculated that malaria was indigenous in North America and Europe, as well as in tropical regions. This is evident in MacCulloch’s emphasis on the global reach of malaria:

But can we forget that we also suffer with Italy and with Greece, with Africa and the West and the East, with the entire world? As travellers, as residents, as warriors, as colonists, we partake with all; and as they suffer, so do we. Let residents, let travellers, let colonists say if it be not so. War at least cannot forget what it suffers, what it has suffered, from this cause; from that Malaria of which it is too often ignorant, which, too often thinks fit to despise. If the sword has slain its thousands, the Malaria has slain its tens of thousands. … This is Malaria, the neglected subject to which I am desirous of calling attention, that, by this, its powers may be diminished: Malaria, from which even ourselves, here in England, are not free, though, from ignorance, unaware of it, or from unwillingness to receive conviction, shutting our eyes to the truth.[7]

When the term malaria entered English medical literature in the 1820s, it referred to a speculative cause of many diseases, especially fevers. By the close of the nineteenth century doctors began using it as a clinical term to describe a specific disease that included the symptoms of intermittent and remittent fever and chills, which corresponded with the present-day medical definition of malaria as a set of diseases caused Plasmodia parasites.

Endnotes

[1] Bruce-Chwatt, 156.

[2] Macculloch, Malaria (1829), 5.

[3] Macculloch, Malaria (1829), 196-198.

[4] Caldwell, 1, 11-12, 17.

[5] Aiton, 60.

[6] Macculloch, Malaria (1829), 6.

[7] Macculloch, Malaria (1829), 8.

Sources

Bruce-Chwatt, L.J. “John MacCulloch, M.D., F.R.S. (1773-1835) (The Precursor of the Discipline of Malariology).” Medical History 21, no. 2 (1977): 156-165.

Mullen, Gary and Lance Durden eds. Medical and Veterinary Entomology 3rd ed. Elsevier Academic Press, 2019.

*Urmi Engineer Willoughby is the Molina Fellow in the History of Medicine at the Huntington Library. She received an F.C. Wood Institute Travel Grant from the College of Physicians of Philadelphia in July 2019.