– by Elizabeth Schexnyder*

I’m always on the lookout for materials that have a connection to leprosy. In particular to the leprosarium established in Carville, Louisiana. Hansen’s disease is another name for leprosy.

Last year, a visitor from Philadelphia toured the National Hansen’s Disease Museum in Carville, where I am the curator. He suggested that I look into the collections at the Mütter Museum and Historical Medical Library. He thought we had much in common. And so we did.

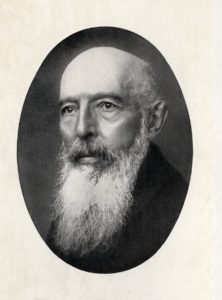

I planned a research trip to the Library in Philadelphia to examine one particular collection—the Dr. Albert S. Ashmead Papers (1869-1910). Dr. Ashmead was a physician who worked in Philadelphia and New York in the late 19th—early 20th century.

According to the National Cyclopaedia of American Biography ”Dr. Ashmead has made an extensive study of leprosy, having had extensive opportunities of studying that disease in the Far East, and is internationally regarded as an authority on the subject. He was one of the founders of the Berlin Leper Conference of 1897”.

The most famous leprologist of the day was Dr. Gerhard Armauer Hansen. Hansen, a Norwegian, discovered M. leprae, the bacillus that causes the disease, under the microscope in 1873. It was the first time a germ was linked directly to a disease.

Years later, when patients and forward-thinking medical professionals were attempting to break the linkage of the word “leprosy”, with all of its negative connotations, to the disease caused by M. leprae, Hansen’s name was evoked and “Hansen’s disease” was born, with mixed results. As a public health educator, I have found that the terms must be used interchangeably when telling the story of leprosy, or Hansen’s disease, in the United States.

The archival holdings in the Historical Medical Library suggest that Hansen and Ashmead carried on a correspondence from the 1890s until their deaths in the early 20th century. They were both intricately involved in the structuring of the first International Leprosy Congress in 1897. The location of the first congress quickly became political. Before Berlin became the designated host city, Hansen wrote to Ashmead “in my opinion the best place [to hold the conference] would be Bergen [Norway], because we have nothing to learn from others, but would give them our good advice, and here in Bergen, they could study our measures in place.” (Hansen to Ashmead, 9-28-1896). Also, Norway didn’t have the funds to send experts to a conference in a faraway location. What Hansen wanted to teach was that mixed isolation of patients—isolation in hospitals and in families—would achieve a drop in disease rate.

Hansen felt it was his duty to do all in his power to prevent the spread of leprosy. But he didn’t suffer fools gladly. “…when I tell people how to do, I think to have done my duty. If they will not follow my advice, they are in my opinion stupid, and stupid people are not to be helped.” (Hansen to Ashmead, 11-1-1896). Hansen’s letters also hold some chastisement for Ashmead. In December 1896, Hansen wrote, “I very much appreciate your zeal, but think a moment! You never can oblige a man to do what he does not like to do, if it is in his power not to do it.” (Hansen to Ashmead, 12-4-1896). Tough love, Hansen-style.

Ashmead and Hansen were interested in purported “cures” for leprosy and maintained contact with other doctors who were exploring alleged treatments. In January 1896, Hansen notes “A week ago I received the Carrasquilla serum…but as I do not know in what quantities and how often it is to be applied I beg you to give me some hints in this point.” (Hansen to Ashmead, 1-03-1896).

A month later, Luis Alvarez, a physician working with the Hawaiian government, solicited Ashmead for the latest information “…Kitasato (a Japanese bacteriologist) has found a remedy for leprosy; and in the last N.Y. Medical Record it is stated that the government of Colombia has ordered that the remedy for leprosy of Dr. Carrasquilla of Bogota be used throughout Colombia. Will you be so kind enough to send me any information you may have in regard to Kitasato’s or Carrasquilla’s treatment?” (Alvarez to Ashmead, 2-22-1896). And then the archives trail grows cold. There are no follow-up reports on the results of the tests. The Carrasquilla serum is identified as “antileprous” and the Kitasato remedy involved the injections of an “antitoxic serum”, but what did they actually contain?

At the same time, Ashmead connected with a Mr. G. M. Bowie, the proprietor of a lumberyard across the Mississippi River from the Louisiana Leper Home. Bowie, a member of the “Home’s” Board of Control, was investigating a claimed cure of leprosy by an Arizona man, who got it from a Mexican man named Ortiz. The patient, William Gisclar was a “man on Bayou La Fourche whom it was claimed had been cured…in 1887”. (Bowie to Ashmead, 8-11-1896). But there is no word on what the Mexican cure consisted of. Not easily discouraged, a few years later, Bowie notes that “Dr. Pearce, the Dr. in charge of [LA] leper home…told me that he had just rec. the 50# of bark & would commence on 3 patients next Monday. (Bowie to Ashmead, 2-7-1900). The bark in question may have been willow bark, a “cure” which regularly made the circuit. Bowie closes the letter with “My only object in sending these letters to you is … as you are well known as an expert on this subject it might lead to a vast benefit to the afflicted people who enlist my sympathy”. And they needed sympathy. There would be no viable treatment for leprosy until the 1941 breakthrough sulphone drug trials at the National Leprosarium in Carville under Dr. Guy Faget.

Ashmead also had a deep interest in anthropology which he combined with his leprosy research in an interesting way.

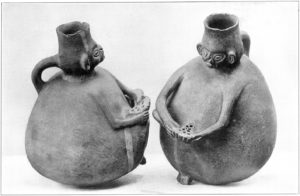

He exchanged letters with a Pre-Columbian expert, William Holmes of the Field Columbian Museum Chicago, and others with a similar interest: Augustus Le Plongeon (1826 –1908) a French-American, amateur archeologist, antiquarian and author who studied the pre-Columbian ruins of America; and Dr. Juliano Moreira (1872 -1933) a Brazilian psychiatrist, often regarded as the founder of psychiatric discipline in Brazil—to name a few. Ashmead thought he saw leprous deformity in pre-Columbian art.

Hansen was helpful— “I sent you a photo of a leprous-hand…You can see the ossa metacarpi, especially the first and the fourth, atrophied …The photo of the skeleton of the hand will suffice, I think, for the comparison with the Peruvian skeletons. (Hansen to Ashmead, 2-2-1895). Ashmead was examining pre-Columbian Peruvian mummy bones for evidence of leprosy. He didn’t find any.

So, was leprosy represented in pre-Colombian art? Dr. Amant Henry-Ohmann-Dumesnil, a dermatologist, summed it up in his letter dated 8-21-1906, “I do not contend that I have any proof to offer that there is any evidence of any precolumbian [sic] leprosy… [the figurines] presents absolutely no evidence of leprosy, syphilis or any other disease”. (Ohmann-Dumensil to Ashmead 8-21-1906). Today, experts agree that leprosy did not exist in the Americas before European colonization.

There was much more. I haven’t even touched on Ashmead’s theory of Hawaiian patients infecting the healthy population by catching and selling leprous fish (they did not). Or that Ashmead exchanged letters with Brother Joseph Dutton—who was Fr. Damien’s back-up in Molokai’s leprosy settlement—and that Dutton was afraid that he, too, like Damien before him, had developed leprosy (he did not). Or that Ashmead collected and retained critical press he received over the years and it’s sprinkled through the collection (I’m not sure I would have done so!). And, I learned, that it’s never been easy to organize a conference.

Leprosy is now a treatable disease, and Ashmead’s theories have long ago been disproven. But to echo the words of G. M. Bowie, member of the LA Leper Home Board of Control “I cannot help admiring the thoroughness with which you [Ashmead] run down everything pertaining to leprosy—[but] I am still after the Mexican remedy which is supposed to have cured the son of Emile Gisclair…” (Bowie to Ashmead, 11-14-1896)

Sources:

[1] Image: Dr. Albert Ashmead http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0104-59702003000400008

[2] Image: Dr. Armauer Hansen, from the National Hansen’s Disease Museum Collections.

[3] Image: Indian Camp Plantation c. 1894, from the National Hansen’s Disease Museum Collections.

[4] Image: This content downloaded from 70.168.195.84 on Sat, 24 Feb 2018 14:00:03 UTC

[5] Image: Schexnyder, personal collection.

*Elizabeth Schexnyder is the Curator of the National Hansen’s Disease Museum in Carville, Louisiana. She can be reached at eschexnyder@hrsa.gov. For more info on the National Hansen’s Disease Museum see www.hrsa.gov/hansens-disease/museum.