We have nearly come to the end of #MedievalMonday posts. This week we’re going to look at two uncatalogued documents, neither of which have any provenance or accession number attached to them.

We have nearly come to the end of #MedievalMonday posts. This week we’re going to look at two uncatalogued documents, neither of which have any provenance or accession number attached to them.

The text on this binding is part of Thomas Aquinas’ Summa Theologiae. The front cover contains a section of the Third Part [Christ], Question 68 [Of Those Who Receive Baptism], Articles 8 [Whether faith is required on the part of the one baptized] and 9 [Whether children should be baptized]. The back cover contains a section of the Third Part [Christ], Question 72 [Of The Sacrament of Confirmation], Articles 4 [Whether the proper form of this sacrament is: “I sign thee with the sign of the cross,” etc.] and 5 [Whether the sacrament of Confirmation imprints a character].

Medieval monks were expected memorize all 150 psalms, and they were commonly sung as part of Mass and the Divine Offices. The music on this binding appears to be part of Psalm 56: “Misit de c[a]elo et liber[avit]…”.

This manuscript dates to circa 14th century, based on the script (a Gothic book-hand), and the composition of the actual text.

The volume was catalogued in our system with the note “Bound in a leaf from a medieval Latin ms. (paragraph marks supplied in alternating red and blue, and capital strokes supplied in red) of a religious text on purgatory; over paper boards.” Even without the acknowledging the script, a text referring to purgatory gives us a place to start, as the word purgatorium is believed to have first appeared in the 12th century.

It’s hard not to have favorites when working in a special collections setting. While searching through our incunabula, I found one bound in a manuscript that I had not seen previously. This particular wrapper has now become one of my favorite items in the collection, and one that I intend to continue researching when time and other duties allow.

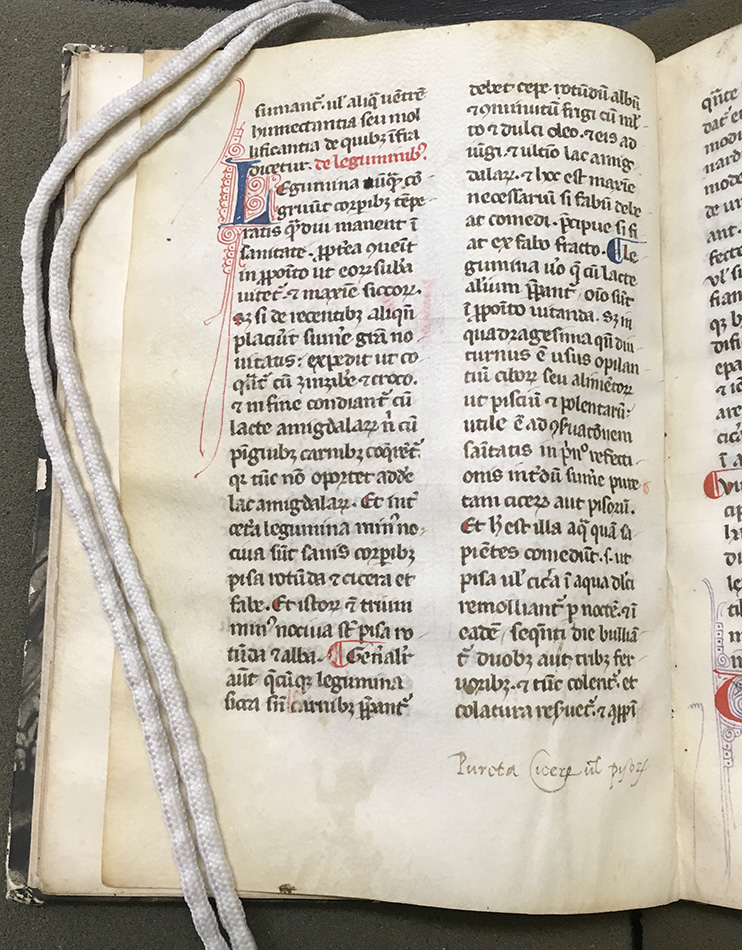

Over the past few months, we’ve looked at various parts of medieval manuscripts – catchwords, ink (here and here), illuminations (here, here, and here), etc., etc. Today we are going to look at the script of 10a 210 (Arnald of Villanova’s Regimen sanitatis ad regem Aragonum).

Unfortunately for us, medieval manuscripts are not usually dated. The Library is lucky to have one, Macer Floridus’ De virtutibus herbarum (1493, call no. 10a 159) in which the scribe has not only written the date it was completed, but also his name (check out this earlier blog post here). The Library’s copy of Lilium medicinae is also dated: 20 June 1348, the day after the feast of Corpus Christi. That’s 669 years ago, tomorrow.