– by Patrick Magee, Visitor Services/Gallery Associate

Have you been to your eye doctor lately? The process might have been a little bit different than it was ten or twenty years ago, with developments in optometry resulting in new tests, diagnostic processes and equipment. In some instances, dilation is not even needed for a full exam to be completed anymore! Now, recognizing that these changes have come within many of our lifetimes, can you imagine how much different ophthalmology was a hundred years ago? What about during the Renaissance era? Through the Digital Image Library, we have assembled a collection of images and historical records that show off just what Renaissance era eye doctors could do with the tools and knowledge of the time. Keep in mind some of the forthcoming imagery (both literal and written) might not be for the faint of heart!

If the concept of a Renaissance-age eye doctor surprises you, consider ophthalmology at its simplest. “An ophthalmologist diagnoses and treats all eye diseases, performs eye surgery and prescribes and fits eyeglasses and contact lenses to correct vision problems” (What Is an Ophthalmologist). While the arrival of contact lenses was still a little way off, medical treatment for eye issues such as cataracts was slowly improving and being established as a reliable field during this era.

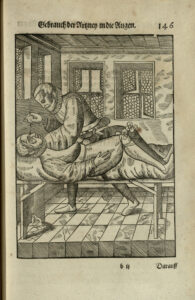

As the woodcuts illustrate, when medical issues of the time were visible and tangible, they were easier to address. Going back years earlier, we can get a sense of what was considered possible and actionable medical science in the years preceding the renaissance: “Medieval surgeons became experts in external surgery, but they did not operate deep inside the body. They treated eye cataracts, ulcers, and various types of wounds” (Medieval and Renaissance Medicine: Practice and Developments).

Modern technology allows medical science to move at a much faster speed now, but Renaissance era doctors still had a foothold when it came to diagnosing conditions. For example, the ophthalmologists of the era were able to detect and treat what we know now as glaucoma. At this point “[t]he lens was understood to be normally located anteriorly and capable of causing visual disorders by pressing against the iris. Lens disorders that did not improve with couching could produce a green pupil and a hard eye” (Leffler, Christopher T, et al). As inferred, some disorders were able to be treated by couching, which “involves depressing an occluded crystalline lens to the bottom of the vitreous chamber” (Baker).

In the times since these woodcuts were made, several different major means of treating glaucoma have emerged and replaced the couching method. For some glaucoma patients, eyedrops can be used regularly as treatment, while others elect to get surgical help either via laser surgery or via operating room procedures like cataract surgery, trabeculectomy, and a glaucoma drainage device. The surgical tools available at present allow for much more safe, accurate, and precise incisions to be made than those that would have been possible in the Renaissance or Middle Ages. With these, higher quality and longer-term ophthalmological treatments are available (Boyd).

Historical records like the above woodcuts show us a period in medical science that was defined by practical solutions in the face of technological limitations. Though the surgery represented therein is more primitive and painful than what eye patients have as options today, at the time it was foundation-shifting and offered the most promise of a better life those with eye conditions had ever been able to experience. If you want to learn more about your eyes (with some eye-popping visuals), both the Mutter Museum and its online digital library offer plenty of material that prove there is more to the complicated science of seeing than just believing.

Works Cited

Baker, Tawrin. “The Oculist’s Eye: Connections between Cataract Couching, Anatomy, and Visual Theory in the Renaissance.” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, vol. 72, no. 1, 2017, pp. 51–66., doi:10.1093/jhmas/jrw040.

Boyd, Kierstan. “Glaucoma Treatment.” American Academy of Ophthalmology, 12 Dec. 2020, www.aao.org/eye-health/diseases/glaucoma-treatment.

Leffler, Christopher T, et al. “What Was Glaucoma Called Before the 20th Century?” Ophthalmology and Eye Diseases, Libertas Academica, 8 Oct. 2015, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4601337/.

“Medieval and Renaissance Medicine: Practice and Developments.” Medical News Today, MediLexicon International, www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/323533.

“What Is an Ophthalmologist?” American Academy of Ophthalmology, 7 Apr. 2021, www.aao.org/eye-health/tips-prevention/what-is-ophthalmologist.