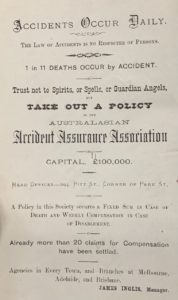

For some, Fall is a time for cozy sweaters, stepping on crunchy leaves, and enjoying all things pumpkin spice. For others, the autumnal season also marks a thinning of the veil between the mortal and spiritual planes. Holidays like All Souls Day allow the living to remember and commune with the spirits of the departed. This presents a unique opportunity to examine a few of Historical Medical Library’s materials on the topic of Spiritualism, the 19th century movement that asserted spirits could communicate directly with the living through special tools or mediums. This small smattering of resources on Spiritualism provides an interesting opportunity to examine matters of the soul and Spiritualism through the lens of science and medicine.

The American Spiritualist movement officially began in 1848 in the suitably sinister states of New England. Quaker abolitionists Amy and Isaac Post investigated claims of mysterious raps and knocks on the walls of a farmhouse in New York. The noises only manifested in the presence of the two girls who inhabited the house, Kate and Margaret Fox. After a series of visits to the Fox household that convinced the Posts of the girls’ talents, the Spiritualism movement gained a large foothold and quickly spread in their Quaker abolitionist community. Initially, spirits only communicated with knocks in response to yes or no questions, but as time went on, mediums wrote full messages from spirits with the use of planchettes or special machinery and were even able to produce spectral figures. These interactions enabled the living to alleviate anxieties related to the death of loved ones and process their grief in a more direct manner.

As with every movement, critics soon began asserting their opinions and their fears for the health of the followers of Spiritualism. The chapter “Spiritualism Considered as an Infectious Mental Disease” of Mediums and Their Dupes opines that Spiritualism is “truly the most insidious kind of deception is that which truth and falsehood are skillfully interwoven.” The author says that no spirit communicates with the medium or controls the planchette or moves the medium’s hand; rather, the author contends that Spiritualist followers fell victim to a combination of suggestion and a phenomenon they call “expectant attention.” Much like when a person yawns and the rest of the room follows suit, all it takes is one persuasive idea, a lack of resistance from the audience, and the idea of spiritual contact is seemingly confirmed. The movement of a planchette is often a “hysterical tendency of the subject,” or voluntary movement of the subject created by their intense desire for spiritual connection or answers.

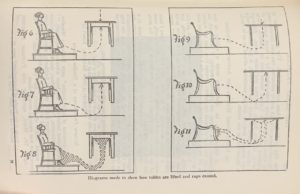

In addition to the power of suggestion, many in the scientific community blamed the use of cheap optical tricks. C.J.S. Thompson, author of The Mystery and Lore of Apparitions: with Some Accounts of Ghosts, Spectres, Phantoms and Boggarts in Early Times, explained how optical illusions could confound the eye and make people think they saw apparitions.

Thompson dedicates multiple chapters to the pursuit of explaining common illusions and hallucinations related to Spiritualism. First, he creates a distinction between the two experiences, defining illusions as false interpretations of external objects. Hallucinations, he says, are subjective sensory images which arise without the aid of external stimuli, but are projected outwards and thus assume apparent objective reality. A hallucination could spring from disease of the sensory organs, an intense state of physical or emotional exhaustion, or the interference of drugs or poisons. Thompson raises the question of whether people saw or communicated with the dead, or if they simply had a physiological condition that lead them to the experience.

But some Spiritualist supporters suggested that those illusions provided a glimpse of something greater. In his work The Great Problem and the Evidence for its Solution, George Lindsay Johnson argues that the sense of perception originates not in the nervous system, but the soul. Furthermore, the apparitions and communications operated according to psychic laws and should not be held accountable to the laws of physics. The book, the author wrote, was meant to “establish as prima facie case for the veridical nature of these strange phenomena” and open the minds of Materialist naysayers.

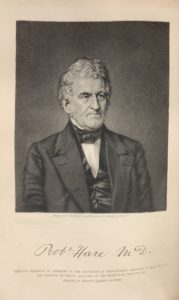

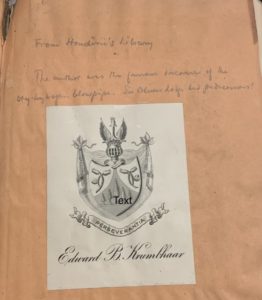

But one of the more notable supporters of Spiritualism actually used his background in the physical sciences to validate his Spiritualist beliefs. Dr. Robert Hare enjoyed a successful career as a chemist and professor at the University of Pennsylvania. His work on the oxyhydrogen blowpipe, a blowpipe which used oxygen and hydrogen to create an intense flame, earned him the prestigious Rumford Medal in 1839. But at the end of his career, he left his post abruptly to dedicate his time to studying Spiritualism.

Dr. Hare worked with local Philadelphia mediums, including a Mr. Lanning who had offices at 124 Arch Street. They first met when Dr. Hare received a letter from the medium explaining Mr. Lanning had a message from the spirit world from Dr. Hare. Mr. Lanning did not know from whom the message came, only that it pertained to a cause close to Dr. Hare’s heart. The spirit’s letter encouraged Dr. Hare to continue his support and pursuit of Spiritualism and not to give in to his self-doubt about his life choices. Dr. Hare found the language and tone of the spirit’s letters so different from Mr. Lanning’s, he concluded that they could not have come from Mr. Lanning’s brain.

The rest of Dr. Hare’s book includes exhaustive accounts of other spiritual contact. He also provides a dense chapter devoted to the science of Spiritualism and experiments he ran to prove the existence of spirits. Dr. Hare’s ultimate goal in Spiritualism was the pursuit of truth and happiness for all beings, both living and in the spirit world. He believed that evil and “intemperance might be eased, or completely eradicated,” if the living were to communicate with the spirit world.

This is by no means a complete look at medicine’s reactions to Spiritualism. Indeed, the Historical Medical Library holds an abundance of material for further investigation. Although the Reading Room is currently closed to researchers due to COVID-19 restrictions, take some time to search our catalog for terms like Spiritualism or Mesmerism and start making a wishlist of materials to request during your next visit to the Library. In the meantime, to continue exploration into medicine’s involvement with different ideologies, take a look at the Historical Medical Library’s Digital Exhibit Under the Influence of the Heavens: Astrology in Medicine in the 15th and 16th Centuries.

Sources: