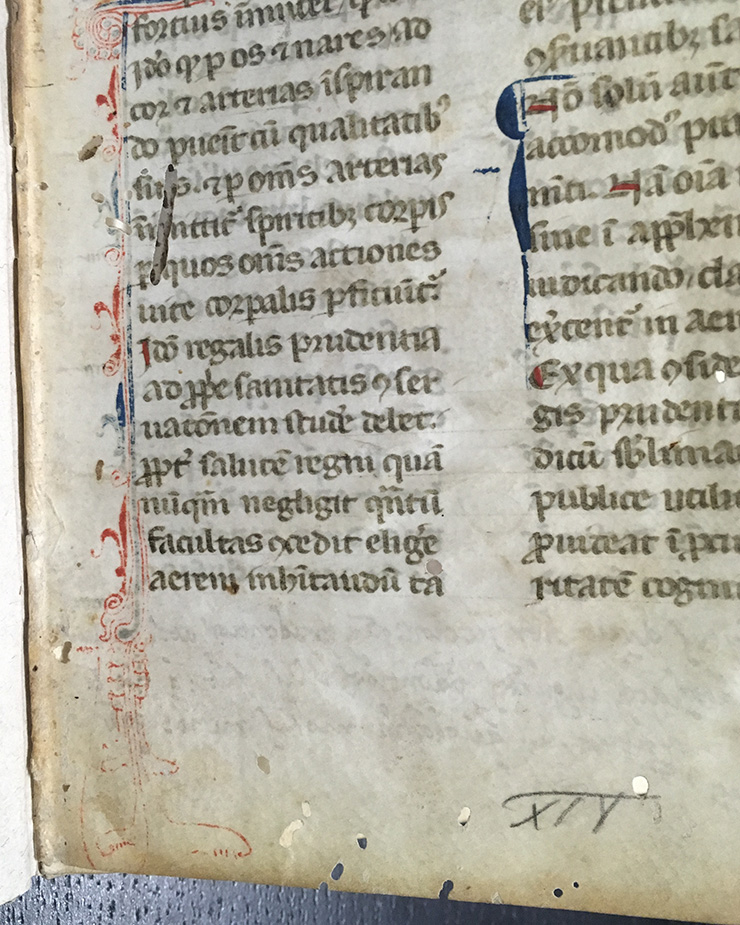

Look closely at the first folio of 10a 210, Arnald of Villanova’s Regimen sanitatis ad regem Aragonum. In the left and bottom margins you’ll see holes. These holes are not the result of parchment tearing or existing holes in the skin (as discussed in this earlier post), but bookworms. Bookworms are “Any of various insects that damage books; spec. a maggot that is said to burrow through the paper and boards,” as defined by the Oxford English Dictionary.

Regimen sanitatis ad regem Aragonum. Spain or southern France; 14th century or c.1400. Call number 10a 210.

Bookworms were often beetle or moth larvae, and seemed to enjoy eating through not only parchment, but also boards and leather covers. (See 10a 249’s cover here.) Not only is it interesting to see which letters the bookworm seemed to prefer eating (I’ve seen an example of one who loved the letter e for some reason), but DNA can be extracted, which tells researchers what kind of beetle the bookworm was, where the manuscript was made, and the evolution of the bookworms themselves.

People were familiar with bookworms in the Middle Ages; in fact, Riddle 47, and Anglo-Saxon riddle from the Exeter Book, is about bookworms. Could you have solved it?

A moth ate words. It seemed to me

a strange occasion, when I inquired about that wonder,

that the worm swallowed the riddle of certain men,

a thief in the darkness, the glorious pronouncement

and its strong foundation. The stealing guest was not

one whit the wiser, for all those words he swallowed.

Sources/further reading:

“bookworm, n.”. OED Online. June 2017. Oxford University Press.

Gibbons, Ann. “Goats, bookworms, a monk’s kiss: Biologists reveal the hidden history of ancient gospels.” Science. American Association for the Advancement of Science. 25 July 2017.

Hostetter, Aaron K. “Riddle 47,” from “Exeter Book Riddles.” Anglo-Saxon Narrative Poetry Project. 2017.