Two weeks ago we talked about lapis lazuli and its use in blue inks, although it was not used in the coat of arms in 10a 189 (see the post here). This week we’ll be looking at the green ink used in 10a 233 – Galen’s De crisibus libri III, in the translation of Gerard of Cremona.

The Library’s copy of De crisibus was written in first half of the 13th century (1200 – 1250) in France. We will learn more about Galen (129 – circa 200/216) in subsequent posts, but he was a Greek physician, surgeon and philosopher in the Roman Empire.

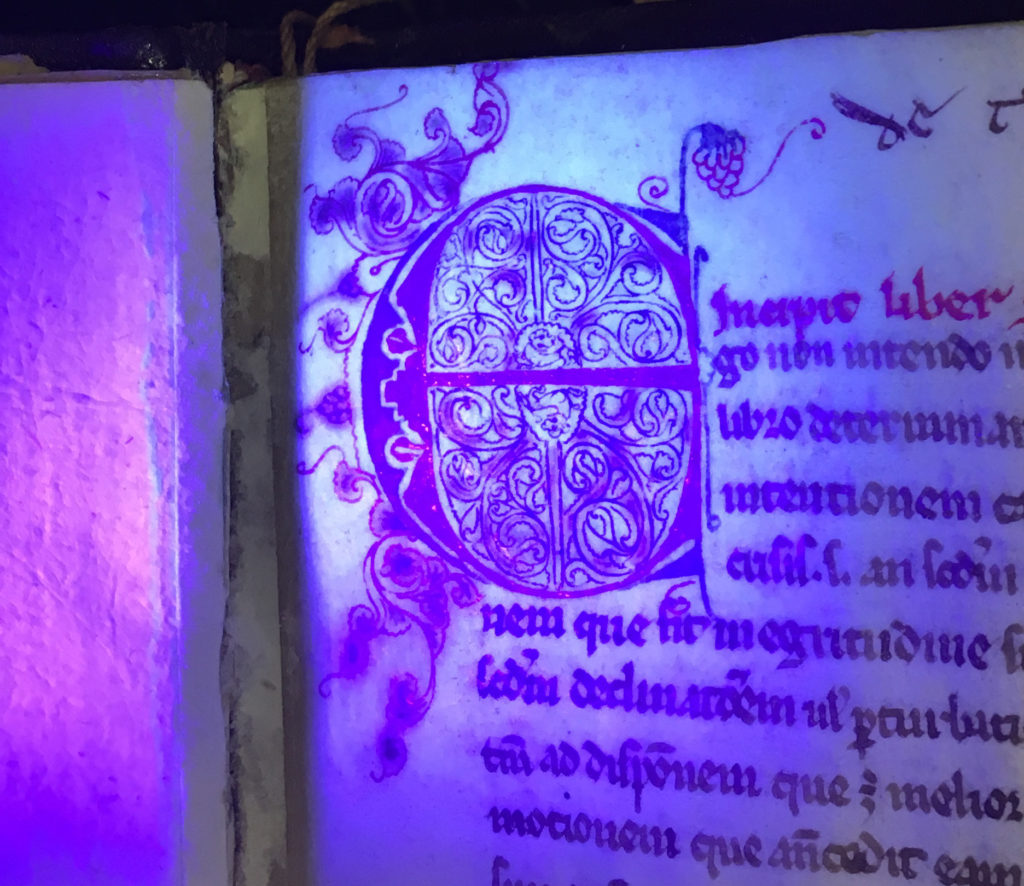

This lovely puzzle initial is on folio 1r of 10a 233, and if you look closely in the center of it, you will see two small beasties. (For more about beasties in initials, see this earlier post.) The penwork in the initial is very fine; the initial in red and blue, the leafy pattern and beasties in blue, and red flourishes with green washes.

However, if you zoom in, you will also see a bit of green inside the initial as well. I didn’t notice that green until I examined the initial with a UV flashlight. Why?

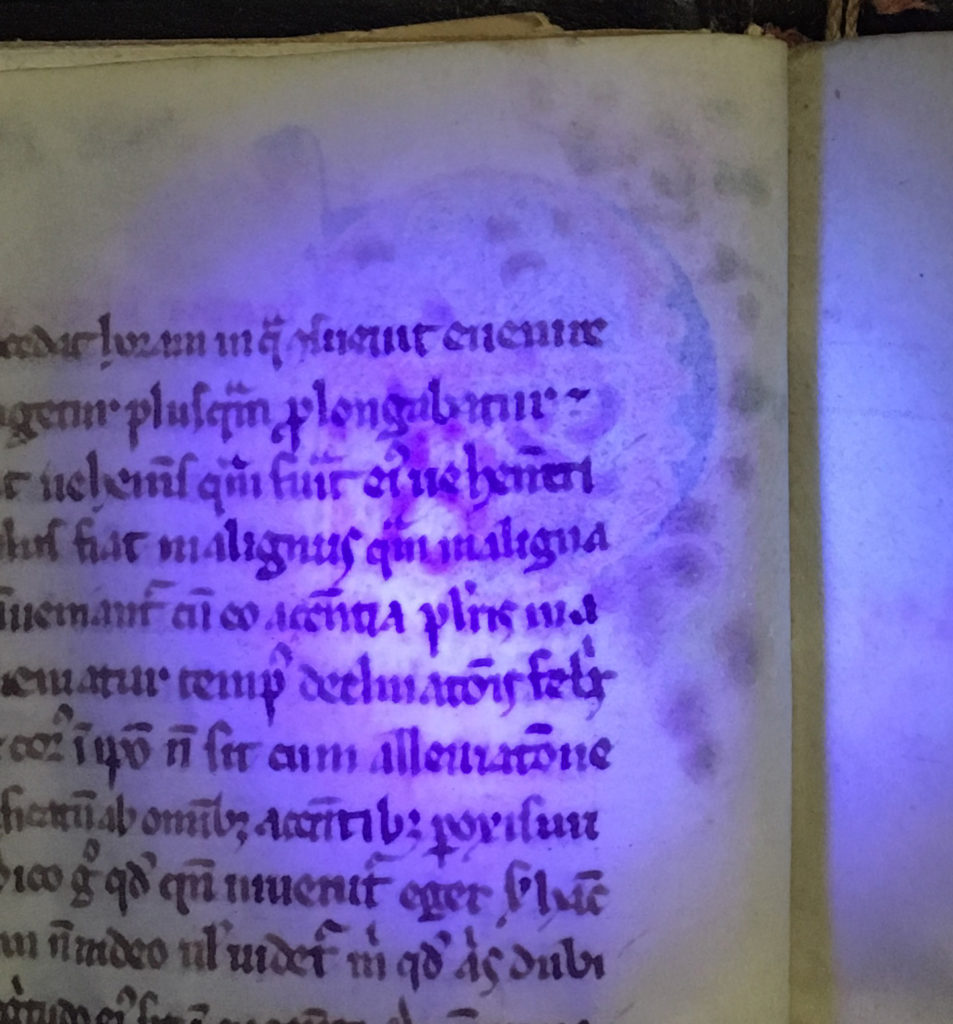

A common way to make green ink was to use verdigris – basically, the corrosion of copper due to air exposure (think of the Statue of Liberty). Verdigris, while beautiful and bright when first applied, is extremely unstable. It will eat through the page of a manuscript eventually, and can often be seen bleeding through to the other side of a folio. The corrosion of the green ink in 10a 233 is easily seen using a UV flashlight.

Sources:

“Overview of Artists’ Materials,” Lab. Illuminated: Manuscripts in the Making. The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, United Kingdom. 2016.