by Wood Institute travel grantee Emily Seitz*

I travelled to the Historical Medical Library of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia this past summer with the help of a grant from the Francis Clark Wood Institute. I was in Philadelphia to research my dissertation project, “What About the Woman?: Managing Maternal Mortality in Philadelphia, 1850-1973,” which asks how turn of the twentieth-century campaigns to lower the United States’ high infant mortality rates affected women’s health and altered the boundaries of the maternal-fetal relationship. The stately oak study table I called home for my two-week stay was piled high with archival materials from the Babies Hospital of Philadelphia, the Pediatric Society of Philadelphia, and the Committee on Maternal Welfare.

Why was I interested in these records? Earlier in the year I happened upon a 2013 American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology article by Mary D’Alton called “Putting the ‘M’ Back in Maternal-Fetal Medicine.”[1] In it, D’Alton urges maternal-fetal specialists to reprioritize maternal health in the wake of recent and startling statistics: maternal mortality rates in the United States have not decreased in over three decades and maternal morbidity rates are on the rise. D’Alton asserts that infant and maternal health are intimately intertwined; in other words, we focus our attention on one body at the expense of the other’s health.

I was researching maternal healthcare in turn of the twentieth-century Philadelphia around the same time I read D’Alton’s piece. Her research led me to wonder if a historical study focused on the evolution of maternal-fetal/infant health could illuminate the current maternal health crisis in the United States. As it turns out, Philadelphia was home to at least three hospitals that specialized in the care of women and children – the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania, the Woman’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and the West Philadelphia Hospital for Women. Woman’s Medical College, or Woman’s Med as it was known at the time, was the first medical college to train women in the United States.[2] The College welcomed its first class in 1850 and quickly developed a national reputation for both its medical training and care. Women from across the state and nation travelled for treatment from women physicians, and young women travelled from as far away as India, Japan, and Syria to receive medical education. While all three of these hospitals offered comprehensive care for women patients by woman physicians, they were well known for their gynecological and obstetric training and care. Significantly, these hospitals also offered specialized treatment for infants and children and emphasized the importance of treating their patients, especially their maternity cases, in a hospital setting.

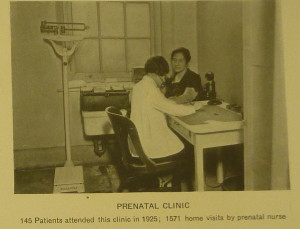

This leads us back to the Babies Hospital and the Pediatric Society, two of the archival collections I worked with while at the Historical Medical Library. In 1911, a group of prominent male doctors working through the Philadelphia Pediatric Society and the exclusively male College of Physicians of Philadelphia established the Babies Hospital of Philadelphia in reaction to the high rate of infant mortality in the city. The hospital had limited wards to house its patients and the staff hosted pre-and post-natal clinics for mothers, though the physicians of the Babies Hospital largely emphasized treatment in the home. I had many questions. Most importantly, I wondered why the Pediatric Society believed pediatricians to be better equipped to manage childbirth than obstetricians, and why they felt a myopic focus on the infant body would yield better results. Further, did the Society consider the women’s hospitals, where this work was already happening, insufficient sites of care? And how were the techniques used in the Babies Hospital different from those used in the women’s hospitals? Finally, I wanted to know if the Pediatric Society’s plan to focus exclusively on the infant body actually worked to decrease infant mortality.

I’m still wrestling with many of these questions, though my preliminary research reveals an interesting story. The Pediatric Society formed the Babies Hospital of Philadelphia out of concern for the growing rate of infant mortality in the City, and infant mortality rates did indeed decline during this time. However, maternal mortality rates increased dramatically. So dramatically, in fact, that by 1930 the city of Philadelphia had the highest maternal mortality rates of the major east coast cities. The Philadelphia County Medical Society formed the Committee on Maternal Welfare in the same year in response to a 1929 Citizens’ Survey sponsored by the Chamber of Commerce that revealed Philadelphia’s maternal mortality rates to be constant despite a ten-year period of falling birth rates.[3] The newly minted Committee was charged with researching the causes of the exceptionally high rate of maternal deaths. The Committee cited four reasons for the high rate: “(1) self-induced and criminal abortions; (2) errors of judgment on the part of the medical profession; (3) lack of appreciation of the need of prenatal care by the laity; and (4) failure of hospitals, organized medicine, and allied agencies to grasp fully their responsibilities and opportunities.”[4] My work connects these events to a broader medical and cultural narrative that began to value the fetal and infant body over the maternal and addresses the ways in which the new medical specialty of pediatrics and the institutionalized field of obstetrics competed for jurisdiction over prenatal care and childbirth and how it affected women’s health and lives. To put it another way, I am interested in what the infant mortality campaigns of the late 19- and early 20-century United States tell us about maternal health.

Why does this story matter? It is important to trace the genealogy of this powerful medical shift because it has real consequences for women’s health today. It is also not a new story. A historical view of maternal-fetal health helps us understand that D’Alton’s call to arms is simply the latest iteration of a nearly century-long shift away from hospitals and medical techniques focused on the care of women and towards those focused on the care of fetal and infant bodies – an important vantage point rendered visible with the aid of the archives.

[1] Mary E. D’Alton, “Putting the “M” back in maternal-fetal medicine,” American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, June 2013, 442-448.

[2] Steven J. Peitzman, A New and Untried Course: Woman’s Medical College and Medical College of Pennsylvania, 1850-1998 (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 2000).

[3] “A Study of Maternal Mortality Committees,” 77.

[4] “A Study of Maternal Mortality Committees,” JAMA, May 5, 1956, 74-77. (MSS 3/0013-01, Series 1.6, Box Two, “Miscellaneous Printed Material”).

*Emily A. Seitz is a Ph.D. Candidate in the Departments of History & Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at The Pennsylvania State University. She received an F.C. Wood Institute Travel Grant from the College of Physicians of Philadelphia in 2015.