– by Wood Institute travel grantee Dr. Edward Allen Driggers*

American medicine has many problems and virtues. One way to “probe” and vindicate the virtues and deal honestly with the problems is participating in writing the history of medicine. Many of the readers of this blog suffer from or will suffer from some sort of medical illness or pathology. One difficulty of illness is talking about it with friends, family, and relatives. American society, much like many other world societies, is oddly squeamish about bodily fluids, belches, smells, and discharges. These passé manners do not serve our open and heartfelt discussions of diseases. For instance, dear reader, I suffer from Irritable Bowel Disease (IBD), specifically Crohn’s Disease. I have had abscesses, discharges, leaky bowels, and, to confess, I do not have all my original parts that I started life with. One of the most difficult things about being chronically ill is explaining these problems to friends, family, or a new lover. How do we talk about difficult things?

Though I traveled to the Historical Medical Library under my fourth F.C. Wood Institute travel grant to view manuscripts needed to finish my first book length project about urinary stones (also an uncomfortable subject), I wanted to peek at sources related to a new project on the history of hemorrhoids (or the “piles” as they were called in the nineteenth century). Many medical school dissertations at the turn of the nineteenth century were written about treating or theorizing about hemorrhoids. Hemorrhoids affected many world leaders, including Napoleon, Marx, and Elizabeth Taylor (just give it a quick Google). About seventy-five percent of people will develop hemorrhoids (based on overall estimates). Hemorrhoids, for those twenty-five percent of the population who have not experienced them first hand, are inflamed blood veins near the anus. In the worst case, these can be like varicose veins found in the leg, which are very painful. However, hemorrhoids, despite their pain, often go away on their own after a period of time. Witch-hazel and other topical medicines are useful, and in extreme cases liquid drugs can be injected directly into the hemorrhoids for quick relief.

How do we start conversations about uncomfortable subjects like hemorrhoids? I found a book in the Historical Medical Library that sought to facilitate those conversations. J. F. Montague wrote the book Troubles We Don’t Talk About, published in 1927. It was a primer for physicians to talk to their patients about uncomfortable conditions.

In the first chapter of his book, Montague questioned the price of modesty in our society, questioning that “It may seem curious that any question should be raised as to whether decency may at times be so exuberant as to be harmful, yet physicians daily see people who have suffered for years with some ailment or other rather than submit to medical examination.” Like jewels, Montague proposed as analogy, modesty can be overdone. Montague argued that diseases beyond those related to lifestyle are simply happenstances to life: “With the exception of diseases produced by licentious living, the majority of morbid conditions are misfortunes of existence to which no shame may be rightly attached.” Progressive for the twentieth century, but still containing elements of shame. However, diseases of the rectum are “innocently obtained,” and naturally occur like any other part of the body. But Montague pointed out that, “…both male and female, there is associated with rectal diseases a pernicious reticence which leads to neglect, harmful attempts at self-treatment or else clandestine consultation with some ‘quack’ doctor.” Apparently, people so neglected the treatment of bleeding hemorrhoids that many physicians had stories where patients became anemic from the loss of blood. Montague cautions that this type of neglect leads to cancer. In 2018, people still put off dealing with colo-rectal issues and often put off colonoscopies. The American Cancer Society recommends screening for cancer after the age of 45. False modesty, Montague explained, can lead to death and unnecessary suffering. Montague reiterated to the reader “What Price Modesty?”

Montague advised physicians how to examine a patient who is embarrassed. He articulated the stakes at performing at examination poorly: “The doctor who hurts a patient while examining him is a bungler, for there is no reason to either cause a patient pain or to cause him embarrassment.” People are in pain, and that pain can be exacerbated by touch, but the doctor can surpass this with what Montague articulates as “skill.” He cautions that “No doctor, who has the best interest of his patient at heart, will every approach the matter of examination roughly.” A poorly performed examination can cause the patient to further hide their conditions to simply get the performative over. An examination can cause conditions to become worse, such as causing anal tears with instruments, and cause the patient to suffer more.

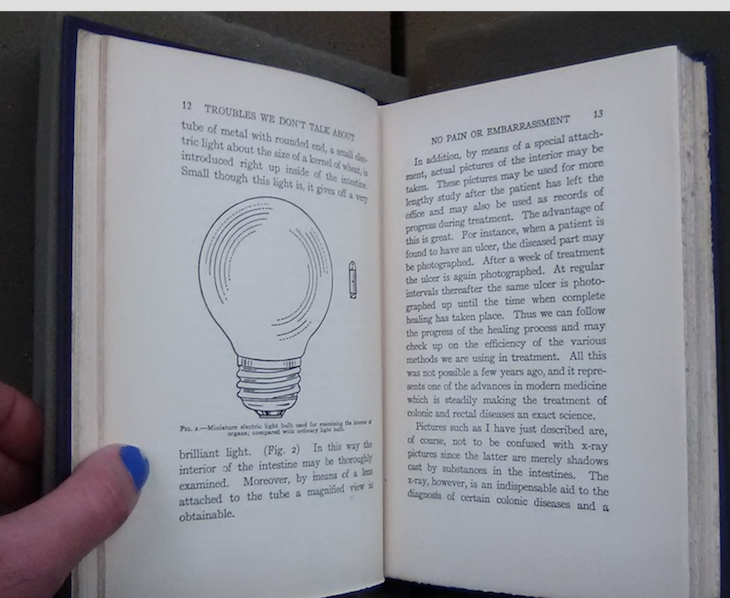

However, Montague pointed out that they are living in an enlightened age where doctors can see inside the body, through the use of a “thin smooth tube of metal” with a light bulb “the size of a kernel of wheat” allowing a fuller view of the intestines or other parts of the body. Pictures and x-rays were even possible. Montague laid out the proper examination procedure. He called for “considerate physicians” to have sheets for a nurse to put over the patient to allow the minimum amount of body parts to be exposed to the examining physician. But asking questions of the patient are not simply enough. Montague called for the use of a “rectosigmoidoscope.” Montague then proceeded to explain to the physician the conditions that people don’t like to talk about, like hemorrhoids.

Hemorrhoids are an old disease and a curiosity in history ad memoriam, though Montague pointed out that physicians need to exercise caution and care. He cautions that “…[T]he most important fact to be known about hemorrhoids is that just as ‘all is not gold that glitters’ so, too, everything given the name of hemorrhoids or piles is not necessarily the exact condition which we doctors call by that name.” Just because a pile bleeds, weeps, or itches, Montague reminded physicians, it is not necessarily a hemorrhoid. Montague reminds the physician that they are most readily identified by reflecting on the varicose vein.

He described to physicians that, “The understanding of the condition is fairly easy. The wall of the veins have become so weak that blood which flows through them stretches them and twists them out of shape. With this in mind, it is easy to understand what hemorrhoids are since they, too, are varicose veins which differ from those occurring in the leg only because of the position of the wall of the rectum and the very different conditions to which they are subjected.” He also pointed out the difficulty of treating hemorrhoids – while a physician could apply bandages to the legs, it is far more difficult to intervene in regards to hemorrhoids.

Montague implied throughout the book that much can be done in regards to treating hemorrhoids but the key to proper treatment is early intervention. Though most everyone will suffer from the condition, diet and proper attention to the colon can lead to prevention.

*Dr. Edward Allen Driggers is an Associate Professor of History at Tennessee Technological University. He received an F.C. Wood Institute Travel Grant from the College of Physicians of Philadelphia in May 2018.