-by Wood Institute travel grantee Melissa Schultheis*

Recipe books are of particular importance to research of seventeenth-century medicine and literature. These texts provide a glimpse of early modern healthcare, both the roles of lay and professional medical providers and the principles that are foundational to the period’s understanding and treatment of the body. The College of Physicians of Philadelphia houses several seventeenth-century medical texts, including MS 10a 214, which is part of ongoing work by Rebecca Laroche and Hillary Nunn. Central to this post, however, is a recipe book signed and presumably owned by John Dauntesey (1529-1694). The Recipe book or MSS 2/070-01 contains an almanac, a transcription of “An hundred and fourteene Experiments and cures of Phillip Theophrastus Paracelsus,” several gynecological recipes, and numerous other recipes in nearly half a dozen hands in both Latin and English.[i] Signed in 1652, the manuscript, as I have discussed elsewhere, seems to represent the seventeenth-century medical community’s transition from traditional to contemporary practices. For example, MSS 2/070-01 frequently relies on Galenic medicine; however, several recipes are attributed to practitioners who work against Galenic tradition, including Paracelsus and Martinus Rulandus. This text’s amalgamation of medical trends seems indicative of the medical community’s shifting views, and with more study I hope this amalgamation can tell us more about those who used and were treated by recipes contained in MSS 2/070-01.

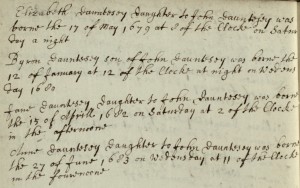

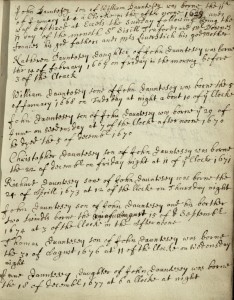

Recently, my work on the Recipe book has focused on tracing the Daunteseys and their location in early modern England. I cannot be certain at this time who the manuscript’s many scribes were, but its last pages contain John Dauntesey’s children’s names and birth dates and have been instrumental in my search for the Recipe book’s location in the seventeenth century. In a section written do-si-do to the rest of the manuscript, a scribe records Dauntesey’s birth followed by the names of his twelve children: Katheren, William, John, Christopher, Richard, John, Thomas, Jane, Elizabeth, Byron, Jane, and Anne.

When I began my search, there was no record of a seventeenth-century Dauntesey in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography or on the digital humanities project Six Degrees of Francis Bacon, which I am currently using to represent the Dauntesey’s social network. As my search went on and I became frustrated, I turned to skimming Google and Google Book results for “Dauntesey,” leading me to investigate the Daunteseys’ and MSS 2/070-01’s connection to Agecroft Hall in northwest England.

My confidence in placing MSS 2/070-01 in Agecroft and the surrounding area of Pendlebury comes from Chetham’s Library’s digital collection of deeds pertaining to the Agecroft estate, which conveys that the Dauntesey family owned the property until the nineteenth century. Upon his death in 1561 Dauntesey’s great-grandfather Robert Langley passed Agecroft and the lands in Pendlebury to his daughter Anne and her husband William Dauntesey. John Dauntesey, their second son, later succeeded his older brother William and inherited Agecroft and its surrounding land.[ii] The Agecroft Collection names John Dauntesey’s five living sons in personal estate documents after his death in June 1694:

Assignment of the personal estate of John Dauntesey, esp, decd

From Christopher, John, Thomas and Byron Dauntesey (4 of the younger sons and executors of the will of John Dauntesey, late of Agecroft, decd) to William Dauntesey (eldest son and heir of the said John Dauntesey, decd).[iii]

His will excludes his third child, John, and fifth child, Richard. In fact, MSS 2/070-01 tells us that John’s third child died at six months. While Richard’s death or disinheritance is not noted in the Recipe book or Chetham’s Library’s documents, the manuscript’s do-si-do genealogy is otherwise consistent with the dates and names used in the deeds in The Agecroft Collection.

Being able to locate its probable location in early modern England provides important insights into the nuances of regional medicine. For example, the hearth tax records 35 hearths in Pendlebury in 1666, eleven of which were located at Agecroft Hall.[iv] Having nearly a third of the hearths in one edifice suggests the hall’s large size and could possibly suggest the surrounding area’s small population. However, as several medicines require forms of cooking and consequently hearths, it could also point to the hall’s overlooked role in healthcare and the production of medicine in seventeenth-century Pendlebury. Additionally, placing the Recipe book at Agecroft Hall may yield insights into healthcare disparities between the aristocratic and working classes. Although much remains to be known about MSS 2/070-01, locating its early modern owner and physical location is instrumental to any research hoping to explore its contributions to medical and historical narratives.

I have recently discovered that Agecroft Hall now stands in Richmond, Virginia after being purchased by Thomas C. Williams, Jr. in the early part of the twentieth century.[v] The hall’s new location alone is unlikely to yield much information about John Dauntesey’s Recipe book although it may suggest how the manuscript ended up in Philadelphia.

Endnotes

[i] Dauntesey, John. Recipe book 1652-1683. MSS 2/070-01. Historical Medical Library at the College of Physicians of Philadelphia.

[ii] “Townships: Pendlebury.” A History of the County of Lancaster: Volume 4. Ed. William Farrer and J Brownbill. London: Victoria County History, 1911. 397-404. British History Online. Web. 23 Jan. 2016.

[iii] The Agecroft Collection, F.3.1-11. A/3/21, Box 2 bdl 2 no 16. Chetham’s Library. Web. 23 Jan. 2016.

[iv] “Townships: Pendlebury.” A History of the County of Lancaster: Volume 4. Ed. William Farrer and J Brownbill. London: Victoria County History, 1911. 397-404. British History Online. Web. 23 Jan. 2016.

[v] “Rebuilding in America.” Agecroft Hall. Agecroft Hall, 2016. Web. 10 Mar. 2016.

*Melissa Schultheis is an MA Candidate in English at University of Colorado Boulder. She received an F.C. Wood Institute Travel Grant from the College of Physicians of Philadelphia in 2015.