– by Josh Bicker, Visitor Services Floor Supervisor

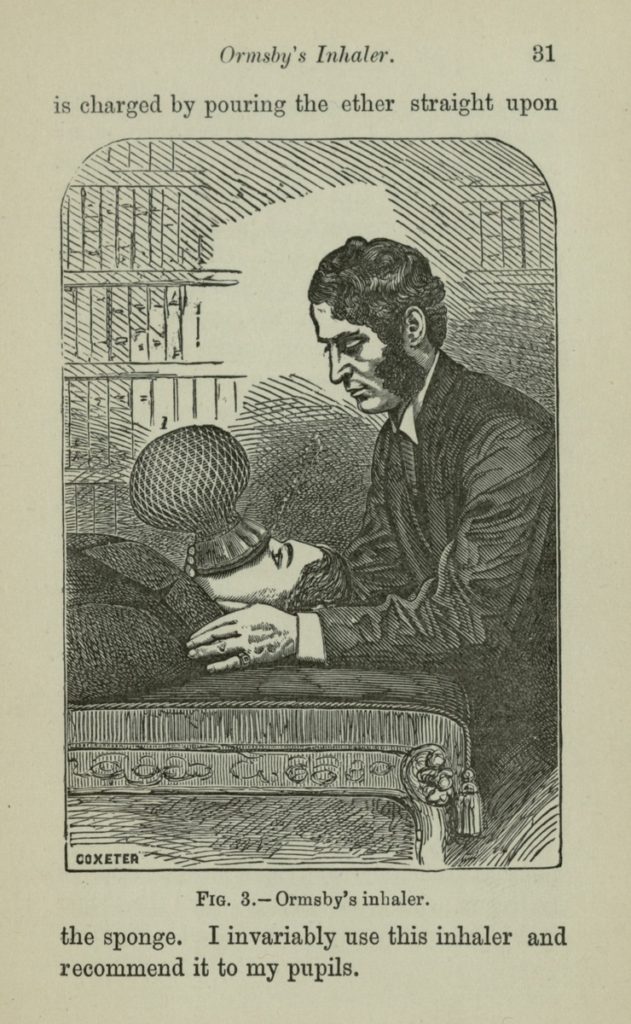

A curious image from our Digital Image Library portrays two men, one of them lying on his back, with a ribbed, balloon like structure over his nose and mouth, as another man looks on, holding the balloon like structure on to his face. From the text around the image, we can tell this is Ormsby’s Inhaler, a variant of a number of different inhalers used at the time for administering Ether as an anesthesia for a patient undergoing surgery. This image is from a general anesthesia guide created by Henry Davis from 1892.

During the second half of the 19th century, there were two types of anesthesia used on patients undergoing surgery. These were chloroform and ether. Ormsby’s Inhaler was a popular brand of inhalers used to administer ether developed in 1877. However, ether had been used before this as general anesthesia for many decades.

Ether was in fact the first anesthesia to be used in surgery. Before ether, surgery was a grim prospect that few people wanted to undertake. Patients and doctors both avoided it. Doctors would rarely perform any deep surgery; the only deep procedures they performed were for external amputations. They would never touch the chest or abdomen. For patients, it was only as a last resort that they would subject themselves to surgery.

Surgery was a violent and grisly experience. Throughout the hallways of hospitals, the screams and cries of patients could be heard. During the procedure, people would have to hold down the patient, or they would have to resort to using pulleys and hooks to keep the patient in place. Doctors would give patients copious amounts of alcohol, ice, and opiates to sedate them. Some doctors were even reported to throw a punch at their patient or hit them with a hammer to make them unconscious. Even mesmerism was utilized, but unsurprisingly it was considered unreliable.

Ether had been around for many centuries before it was used for surgery. It was originally discovered in 1540 by Valerius Cordus, a Prussian Botanist. He made ether by distilling sulfuric acid with fortified wine to make what he termed “oleum vitrioli dulce,” or sweet oil of vitriol. For the next 200 years, ether was used as a medicine, taken in drops as a stimulant to relieve spasms or convulsions. Beginning in the early 19th century, however, it was used as a recreational drug at “Ether Frolics” in the United States. At these parties, American students would cover their mouths and noses with ether-soaked towels, and thus go into a euphoric state.

Dr. Crawford Williamson Long, a physician and pharmacist, attended one of these parties. He observed the effects of ether and noticed that people who fell or got into fist fights did not feel any pain. In 1842, he started using ether for surgeries. He successfully removed a tumor from a patient’s neck using ether as an anesthesia, and the patient felt little pain. However, Long did not publish his results for another seven years, because he wanted to do more testing. Unfortunately, in those seven years, another person got the credit for discovering ether anesthesia, and when Long’s discoveries were finally published, they were dismissed.

T.G. Morton was a dentist who discovered the anesthetic use of ether in 1846. Previously, he had observed a fellow dentist use nitrous oxide, or “laughing gas,” as anesthesia for a medical demonstration. Unfortunately, the patient awoke while under the anesthesia, and he was booed off the stage. After Morton observed this, he consulted with Charles A. Jackson, a chemist. He suggested using sulfuric ether as anesthesia for surgery.

Morton used odor-masking substances to mask the smell of ether and titled his concoction “Letheon”, the river in Greek mythology that caused forgetfulness. In 1846, he used ether during a surgical demonstration at Harvard Medical School. The surgery was a success, and Morton was credited with “discovering” Ether as an anesthetic.

After T.G. Morton’s “discovery,” ether started being used as anesthesia throughout America and Europe. In the United Kingdom, it was first successfully utilized by Dr. Robert Liston. In 1849, ether was officially circulated by the U.S. Army, and was used both during the Mexican American War and the Civil War. In 1847, chloroform was discovered by James Young Simpson, and the two substances became the most popular anesthetics of the day, making surgery a much easier, painless experience.

Ether was originally taken by soaking a cloth in ether and placing it over a patient’s mouth and nose. When Morton did his demonstration in 1846, he used a glass globe with two spouts coming out, with an ether-soaked sponge in the center. The patient breathed in the vapors through one of the spouts. In 1847, Dr. John Snow invented an inhaler which could moderate the intake of ether as well the temperature.

While inhalers and sponges continued to be used, in France doctors started using a device called a Roux Sac. This was a bag lined with pig skin that could be opened and closed to different degrees to change the amount of ether inhaled. A sponge soaked in ether was placed inside the bag, and the opening of the apparatus was placed on the patient’s nose and mouth.

This design became very popular towards the end of the 19th century, and various manufacturers created their own versions of it. Joseph Thomas Clover created a popular version of it, as well as Dr. Ormsby. Ormsby was a New Zealand surgeon who emigrated to Ireland. In 1877, he created his unique portable inhaler. According to a 1896 description of the Ormsby Inhaler, “the face-piece is a cone shaped wire cage, covered externally with leather, and leading a soft leather bag,…” It also featured a tube that extended from the rim which one dispensed Ether into, as well as a valve on the side of the cone.

Towards the close of the 19th century, the sack inhaler method was replaced by the “open drop” method using a mask. For this method, a layer of cloth was placed on top of the patient’s mouth and nose, followed by a metal frame to keep it in place. Drops of ether were administered onto the cloth. This method continued to be used for 50 years, during both World War I and II.

While ether was effective as an anesthetic, it did have its shortcomings. It was highly flammable, and once it was released into the air, it could easily cause explosions. As well as this, patients often felt a chocking sensation, and because the onset could last up to 15 minutes, the patients had to be held down. The odor of ether was often found irritating as well.

With the release of more efficient anesthetics in the 1960s, the use of ether declined. It was quickly replaced by new anesthetics such as halothane and sevoflurane. Today, it is no longer used except in undeveloped countries, where it is a cheaper alternative.

The discovery of ether revolutionized the world of surgery. Surgery went from being something both doctors and patients avoided, to a common, painless practice that helped millions of people.

Sources:

“The Art of Anaesthesia” Science Museum, 26 Oct. 2018, https://www.sciencemuseum.org.uk/objects-and-stories/medicine/art-anaesthesia.

Cedars Sinai Staff. “Into the Ether” Cedars Sinai, 7 May 2017, https://www.cedars-sinai.org/discoveries/2017/05/into-the-ether.html. Accessed 4 Dec. 2020.

Chang, Connie Y. et al. “Ether in the Developing World: Rethinking an Abandoned Agent” BMC Anesthesiol, Vol. 15, 2015, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4608178/. Accessed 4 Dec. 2020.

Duncum, Barbara M. “ETHER ANAESTHESIA1842-1900*” Postgraduate Medical Journal (PMJ), pp. 280-290, 1946, https://pmj.bmj.com/content/postgradmedj/22/252/280.full.pdf. Accessed 4 Dec. 2020.

“Ether” The Wood Library-Museum. https://www.woodlibrarymuseum.org/museum/item/657/ether. Accessed 4 Dec. 2020.

“Ether and Chloroform” History, 26 Apr. 2010, https://www.history.com/topics/inventions/ether-and-chloroform.

Fenster, Julie M. “ETHER DAY: The Strange Tale of America’s Greatest Medical Discovery and the Haunted Men Who Made It’” Oncology Times, Vol. 24, Is. 12, pp. 69-70, 2002, https://journals.lww.com/oncology-times/fulltext/2002/12000/ether_day__the_strange_tale_of_america_s_greatest.36.aspx. Accessed 4 Dec. 2020.

Fitzharris, Lindsey. “How Ether Transformed Surgery from a Race against the Clock” Scientific American, 1 Oct. 2017. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/how-ether-transformed-surgery-from-a-race-against-the-clock/. Accessed 4 Dec. 2020.

“Ormsby’s Ether Inhaler” U.S. National Library of Medicine Digital Collections, https://collections.nlm.nih.gov/catalog/nlm:nlmuid-101434297-img. Accessed 4 Dec. 2020.

Penn, H.P. “THE GEOFFREY KAYE MUSEUM COLLECTION OF PORTABLE ETHER INHALER” Anaesthesia and Intensive Care, Vol. 3, No. 4, pp. 351-354, 1975, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0310057X7500300414. Accessed 4. Dec. 2020.

Ramsay, Michael A.E. “John Snow, MD: anaesthetist to the Queen of England and pioneer epidemiologist” Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent), Vol. 19(1), pp. 24-28, 2006, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1325279/. Accessed 4 Dec. 2020.

Reisch, Marc S. “Ether” Chemical & Engineering News, Vol. 83, Is. 25, 2005, https://cen.acs.org/articles/83/i25/Ether.html. Accessed 4 Dec. 2020.

Shreve, Grant. “19th Century Anesthesia and the Politics of Pain” JSTOR Daily, 26 Feb. 2018, https://daily.jstor.org/19th-century-anesthesia-and-the-politics-of-pain/. Accessed 4 Dec. 2020.

Thomas, Roger K. “How Ether Went From a Recreational ‘Frolic’ Drug to the First Surgery Anesthetic” Smithsonian Magazine, 28 March 2019. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/ether-went-from-recreational-frolic-drug-first-surgery-anesthetic-180971820/. Accessed 4 Dec. 2020.