– by Wood Institute travel grantee Heather Christle*

In 1906, Alvin Borgquist–a little-known graduate student at Clark University–published the world’s first in-depth psychological study of crying, and then appears to have vanished back into a quiet, private life in his native Utah. His study is moving, strange, detached, threaded through with the racist and colonialist assumptions common to this era (and, distressingly, our own). The questionnaire he crafted to solicit data on typical crying behaviors fascinates me, forming as it does a kind of accidental poem. Here, for instance, is Borgquist’s first question:

As a child did you ever cry till you almost lost consciousness or things seemed to change about you? Describe a cry with utter abandon. Did it bring a sense of utter despair? Describe as fully as you can such an experience in yourself, your subjective feelings, how it grew, what caused and increased it, its physical symptoms, and all its after effects. What is wanted is a picture of a genuine and unforced fit or crisis of pure misery.[1]

*

I am more accustomed to thinking of myself as a poet than a researcher, but five years ago I accidentally started to write paragraphs about crying, and once I began to investigate the subject, I could not resist the language and lives it led me to discover. As a poet I have always believed in allowing the work to lead the way, not to decide in advance where I wanted my lines to end up or what their scope might be, and I decided to conduct my crying research the same way. Captivated by Borgquist’s study, eager to find the full, original results of his research, but unable to find his papers housed in any archive, I began to investigate each of the people he listed in his acknowledgments. Halfway through I landed upon a name you may know: Dr. S Weir Mitchell.

Before I planned my trip to the Historical Medical Library this past January, I knew a few things about Dr. Mitchell. I knew he treated the pioneering feminist author and activist Charlotte Perkins Gilman with his famous “rest cure.” I knew that she suffered under his care, and translated that experience into her classic story, The Yellow Wallpaper. I knew that between Weir and Gilman my allegiance was to the woman who, like me, wept through many days of early motherhood. I knew that Weir had suffered a great loss in 1898, when his beloved daughter, Maria, succumbed to diphtheria. I knew that Weir, not just a doctor, but a writer like Gilman and myself, translated his experience into poetry. I knew that in memory of his daughter he wrote what many think of as his greatest poem, “Ode on a Lycian Tomb.” I knew that the poem’s stiff Victorian lines left my lacrimal glands entirely tearless.

*

It did not take long, reading through the archives on a few cold days of mean January rain, to realize that Borgquist’s correspondence with Weir was not to be found in any of the gentle green boxes. Disappointed, but still curious, I turned to Weir’s diaries and letters, hoping to trace the path from his daughter’s death to the composition of his poem.

Unsure of the precise date of Maria’s death, I began late in the year, and found Weir already in grief, recording the events of the day briefly and with little enthusiasm:

I have learned the bicycle–

[…]

Church is for us a sad affair–

[…]

The days run on uneventfully–[2]

And so I turned the pages backward, watching his suffering grow more acute, until I discovered the pages where, verso, Maria lives, and recto, she is gone:

January, Saturday, 22. 1898.

Maria slowly mends

Polly [Mitchell’s wife] in the thick of it

[…]

If Rheum stays my child will die

for whom I would die — endless deaths

There never was any woman as pure as fine as free fr– any form of fault.

January, Sunday, 23. 1898.

[…]

am — Maria rests 4 to 6 — pulse irreg

I know alas these losing fights with death —

9am

I have just told my wife – of M’s perilous state — she said — I will be quiet — I can endure even this — I am not to be kept ignorant —

I promised

My little maid died at 02.30 this accursed day — & we are left alone[3]

And then I had to stop reading, because I was afraid my tears would damage the archival materials.

*

Perhaps one of the most life-altering discoveries I have made since embarking on this project is that to engage in this kind of writing and research is not so different from writing a poem. In writing poems, I have always moved forward one word at a time, waiting to see which surprising correspondences the language would build, trusting that the poem would reveal itself in its own time. Now, writing and researching this work about crying, I am never not in the poem. The world itself, all I read, the people, the art, the weather I encounter, they all belong in a poem that I am not writing, a poem that contains me too, a poem that slowly reveals its generous and surprising connections. I think I cannot write that poem. I can only live in it. So instead, I am writing a parallel book, paragraph by paragraph, day by day.

*

When I stepped away from Mitchell’s diary to halt my crying, I climbed up the library’s back stairs to the break room on the building’s third floor, where I recounted my experience to a couple of people who worked for the College and Library, who were chatting and eating lunch. One told me about the time the sight of a Gutenberg Bible made her weep, and how a concerned security guard bade her step away. The other told me about the day he walked to work at the College, listening to an anthemic new album by a favorite band, and that somehow the intensity – the rightness? the iconicity? – of the experience brought him to unexpected lacrimation.

*

Poets love to tell people that “stanza” means “room.” Downstairs, Mitchell grieves his daughter. Upstairs, this room holds a different set of tears.

*

Still shaken by Mitchell’s suffering, I decided to walk to the Philadelphia Museum of Art, where I could see the memorial sculpture he and his wife commissioned years after Maria’s death, a work of Augustus Saint-Gaudens, titled “The Angel of Purity.” Originally, it stood in St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church, where Maria had been a teacher and parishioner, but as membership declined with the neighborhood’s transition away from residential buildings, church leaders chose to sell the sculpture. (On a different day, when I visited the church, I found it watched over by one lonely sexton.)

The sculpture, smooth and white and serene, seemed a world away from Mitchell’s diary. It was mourning made formal, somehow cold, and not unlike Mitchell’s own monument to his daughter, the poem I mentioned above, where he wrote:

Fair worshipper of many gods, whom I

In one God worship, very surely He

Will for thy tears and mine have some reply,

When death assumes the trust of life, and we

Hear once again the voices of our dead,

And on newer earth contented tread.[4]

The “worshipper” Mitchell addresses in this poem is the figure of a woman carved on a sarcophagus he saw in Istanbul (then Constantinople), on a long trip, he and Polly took to distract themselves from their shared grief. The sides of the sarcophagus (which is still on display Istanbul Archaeology Museum, and is sometimes called “Les Pleurisies”), are decorated with eighteen women, each in a different position illustrating attitudes of sorrow.

In Mitchell’s interpretation, each is, in fact, the same woman, whom the sculptor depicts moving through the many facets of grief. Immediately after seeing it, Mitchell wrote to his son:

The “pleureuses” is not so great [as the sarcophagus of Alexander] but is most affecting — a dozen women in varied attitudes of grief wrap all around the marble — you walk around the sarcophagus and at last are tremendously sorry for these women —[5]

Not surprisingly, Mitchell goes on to say that “As far as the Turk goes they are pearls before hogs,” positioning himself, a white, Christian, American as the acceptable interpreter and appreciator of a piece of Middle Eastern art. Even in his grief, he worked to uphold the oppressive systems that gave him power. Of course. And then sometimes he straddled spheres, doctor and poet, researcher and grieving parent, in such a way that saw him question the limits of his scientific and “neutral” methods:

March, Thursday, 2. 1899

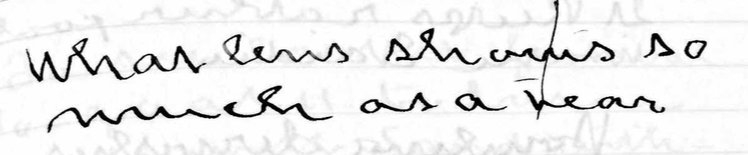

What lens shows so much as a tear[6]

Perhaps that is why I grew so attached to his diaries, where at times his systems seem to break down, where his attempts to smooth his grief over into metered language fall apart. I found, in those pages, a man of ragged lines, a man who moved between poetry and prose, losing whole words to an illegible rush. No matter. He and I could sit in the company of January’s dark days:

January, Monday, 24 1898

Today my child is buried

My wife is ill and cannot see her

I can bear my grief but […] to bear hers

— We left my best maid alone in the hideous place of graves — & I came back to break up [to argue] with my Mary when she said she was lonely —

Ah is not all true sorrow lonely — None can share — so as to make it less —

There is a grief beyond all other grief

To bear the sorrow of some heart so dear

That this sad burden seems past all relief

That time can bring or […] can give us here

Ye who have suffered what today is mine

Are happy if ye escape this added pain

The unbearable anguish that death […]

To weep for those who weep & weep in vain

God help me.[7]

Endnotes:

[1] Borgquist, Alvin. “Crying.” The American Journal of Psychology 17, no. 2 (1906): 149-205. doi:10.2307/1412391.

[2] Silas Weir Mitchell diary, 1898, Box 13, Folder 18, Silas Weir Mitchell Papers, Philadelphia College of Physicians Historical Library.

[3] ibid

[4] Silas Weir Mitchell. “Ode on a Lycian Tomb.” Privately printed.

[5] Letter, S. Weir Mitchell to John K. Mitchell, January 11, 1899, Box 5, Folder 7, Silas Weir Mitchell Papers, Philadelphia College of Physicians

[6] Silas Weir Mitchell diary, 1899, Box 13, Folder 19, Silas Weir Mitchell Papers, Philadelphia College of Physicians Historical Library.

[7] Silas Weir Mitchell diary, 1898, Silas Weir Mitchell Papers.

*Heather Christle has an MFA in Creative Writing from University of Massachusetts Amherst. She received an F.C. Wood Institute Travel Grant from the College of Physicians of Philadelphia in 2017.