– by Josh Bicker, Visitor Services Floor Supervisor

The hobby of collecting trading cards has always been a popular pastime for many people. From trading cards of sports stars and pop stars, to collecting cards of characters from movies and popular TV shows, young and old have shown an interest in this hobby. The reason for collecting cards can vary. For some, it could just be an attractive piece of paper to look at, while for others it is a more serious form of collecting involving scrap books and getting appraisals for each card. Regardless of the reasons, collecting cards has been a pastime for many for a long time.

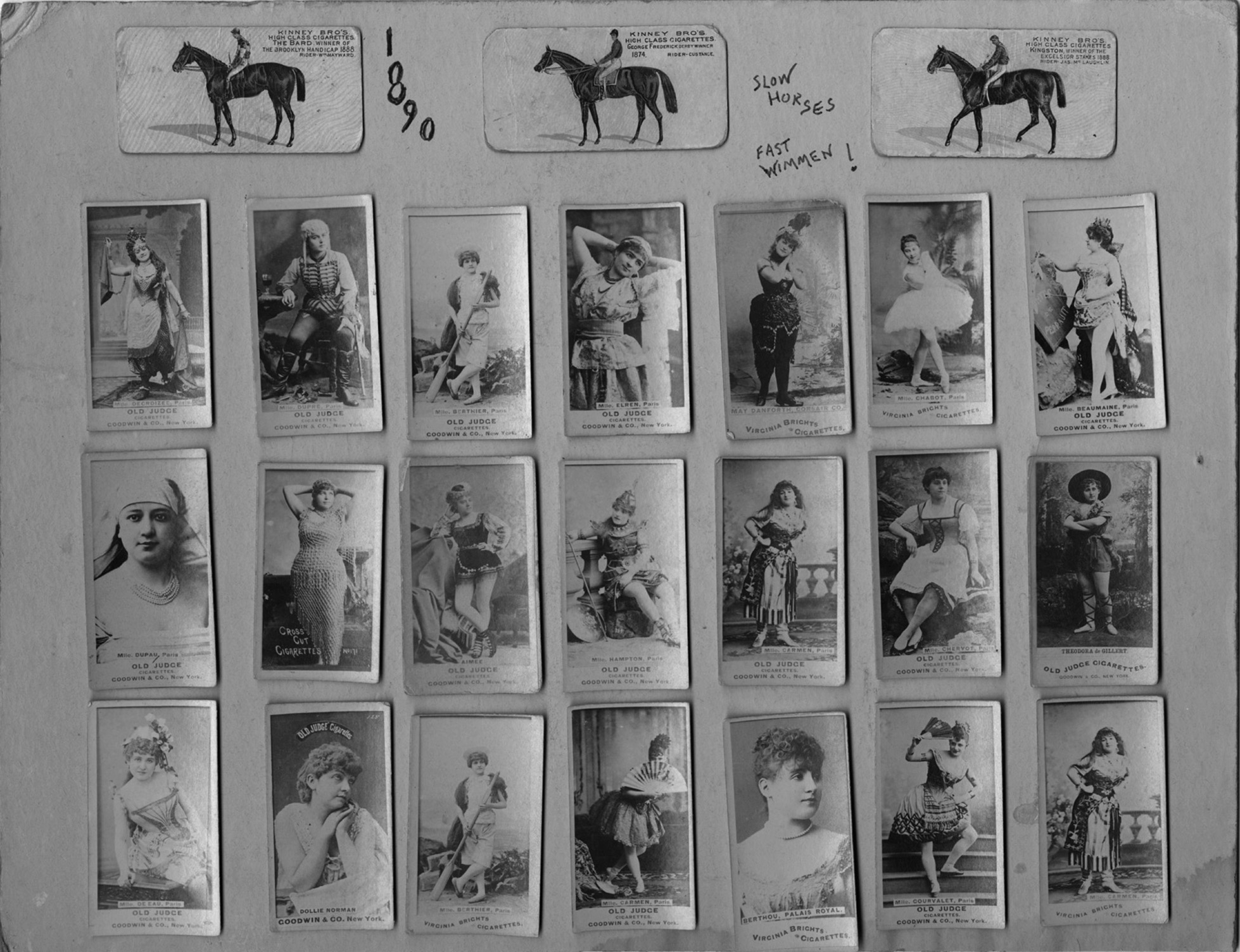

In our Digital Image Library, we find an early example of trading cards. The black and white photograph below is an image of an item from the Philadelphia General Hospital Photographs, and shows us the unknown creator’s collection. The twenty-four cards are laid out neatly on white paper. On top, three cards show horses with riders. These show us popular racing horses and their jockeys. Beneath, presented in vertical rows, there are images of women in exotic costumes and tightly laced waists. These were popular actresses of the time, most of them being French. The writing on the paper reveals the date of 1890, along with a mocking, boyish slogan: “Slow Horses, Fast Women!”

Many people would be surprised to realize these are not simply trading cards, but cigarette cards. Cigarette cards were a popular form of advertising and promotion during the early days of cigarette smoking in the late 19th and early 20th century. In order to make cigarettes a popular form of tobacco, inventive and attractive marketing had to be utilized.

Cigarettes were not the preferred way of smoking until very late in tobacco’s long history in the United States. Tobacco was originally cultivated by Native American tribes throughout the American continents for recreational, healing, and spiritual purposes. The dried leaves of the plant were either inhaled using an early form of a cigar, blown in a pipe, or crushed and taken like snuff. When Europeans arrived later on, they were intrigued by this, and quickly started growing their own tobacco. Tobacco soon became popular throughout Europe. It became one of America’s most lucrative exports, as well as being popular with the locals as well.

By the first half of the 19th century, the use of tobacco was a common pastime in the United States. However, cigarettes were not. While cigarettes were being produced in Europe and Mexico, they were rarely seen in the United States. The most popular forms of tobacco in the U.S. were chewing tobacco or snuff, smoking it in a pipe, or the cigar. Cigarettes were considered a rarity, and not a good one at that. Smoking cigarettes was considered “foppish” and “unmanly.”

This started to change after 1860. Tobacco of all types became more popular with soldiers during the Civil War. After the war, more companies started producing cigarettes because of their relatively cheap production costs. The only issue was discovering a quicker way to produce them, since the process of hand rolling cigarettes was time consuming.

This was solved around 1880 when inventor James Bonsack created a cigarette rolling machine. The machine was able to produce 200 cigarettes. The “Bonsack Machine” was soon bought out by industrialist James Duke of W. Duke Sons & Company, based in North Carolina. James Duke was hugely successful in this, and because of his success, was able to eventually consolidate all his competitors into a single company, the American Tobacco Company.

Even with the mass production of cigarettes, advertising was still important in order to accumulate an audience. Tobacco companies had to find a way to make cigarettes more appealing. The typical cigarette smoker was still stereotyped as a reckless and foppish youth. In order to change this, companies started producing advertisements that used a great deal of military – and particularly Navy – imaging in order to make cigarettes look “manly.”

Tobacco companies also wanted to draw in a crowd of young buyers who could buy their products for generations to come. Cigarette cards were the perfect way to do this. In an age where books were expensive and newspapers had few images, colorful, informative cards were a novelty. Cigarettes at the time came with a taut paper called a “Stiffener” to keep the cigarettes from being bent or crushed in their paper packaging. The first ones printed with images were produced in the 1880s in red and black. Later, they were printed in full color using lithography.

These new “Stiffeners” came with a variety of different images. Much of the early imagery appealed to their demographic, young men, with images of women posing in bathing suits, racing horses, popular theater actresses, and the military.

Soon, however, images tended to be more about entertaining and informing a young audience. There were series done on sports stars, transportation, historic figures, and geography. Every brand had its own special series. The brand W.D. & H.O. Wills did a series on the Kings and Queens of England, with descriptions of the images on the back of the card. Some brands explored subjects of chemistry and biology, and others even had healthy maxims on them, such as “Keep Fit,” and “Safety First.” The Boys and Girls Scouts even had cigarette cards made for their associations.

Brands would release cards in sets of 20-25 cards, and in order to complete a series, one had to buy lots of cigarettes. These series of cards soon became a popular collectable for children, and in England it became common for children to ask a smoking adult if they could have a “fag card.” Even adults started collecting them, and the amassing of these cards came to be called “cartophily.” Over 300 brands produced cigarette cards.

By the 1920s, cigarette advertising not only went after men, but women as well. Previously, a woman smoking was considered deviant and rebellious. By the 1920s, with many more working women, cigarette usage became more common. Cigarette advertisements at the time showed women who smoked as sophisticated and attractive. Along with this, cigarette cards started showing imagery that was thought to appeal to women, such as Hollywood movie stars, like Greta Garbo and Joan Crawford.

Military imagery was still a popular subject for cigarette cards. Images of tanks, airplanes, and other military equipment was common. During the second World War in the United Kingdom, air raid precautions were put on some cigarette cards. As well as this, there were rumors of Germans buying British cigarette cards in order to steal and reproduce their military equipment.

By the 1940s, the Golden Age of cigarette cards was ending. In the United Kingdom, cards were banned as a “waste of vital raw material.” After World War II, cigarette cards became increasingly uncommon, and trading cards started being sold in other ways and eventually sold separately in packs. This of course coincided with increasing evidence of the bad effects of smoking in general that began in the 1950s, and the declining popularity of smoking during the second half of the 20th century.

Cigarette cards serve as a small, but colorful glimpse into a world that is gone, their hobbies, interests and pleasures. These cards serve to show us the joy one receives from collecting attractive and interesting things, whatever and whenever that might be.

Sources:

2000 Surgeon General’s Report Highlights: Tobacco Timeline. CDC. 21 July 2015. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/sgr/2000/highlights/historical/index.htm. Accessed 1 Dec. 2020.

Barr, Sabrina. “How Smoking Adverts Have Evolved Over the Decades, from a Gentleman’s Pastime to a Life-Threatening Activity.” The Independent. https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/health-and-families/smoking-adverts-cigarettes-tobacco-history-philip-morris-first-world-war-a8596196.html. 22 October 2018.

Blum, Alan. “A History of Tobacco Trading Cards: From 1880s Bathing Beauties to 1990s Satire” Tobacco and Health. 1995, pp. 923-924.

Brandt, Allan M. The Cigarette Century. New York, Basic Books. 2007.

Degering, Ed.F. “Cigarette Cards and Chemistry” Journal of Chemical Education, 1937, pp. 394-395.

Gershon, Livia. “A Brief History of Tobacco in America” JSTOR Daily. https://daily.jstor.org/a-brief-history-of-tobacco-in-america/ 10 June 2016.

Hannah, Mary‐Kate, et al. “Contextualizing Smoking: Masculinity, Femininity and Class Differences in Smoking in Men and Women from Three Generations in the West of Scotland” Health Education Research, Volume 19, Issue 3, 2004, pp. 239–249.

Henningfield, Jack. Smoking. Britannica. 19 Nov. 2020. https://www.britannica.com/topic/smoking-tobacco. Accessed 1 Dec. 2020.

Johnson, Ben. “Cigarette Cards and Cartophily” Historic UK: The History and Heritage Accommodation Guide. https://www.historic-uk.com/CultureUK/Cigarette-Cards-Cartophily/ Accessed 1 Dec. 2020.

Petersen, William J. “Collecting Cigarette Pictures” The Palimpsest, Volume 51, Number 3, Article 2, 1970, pp. 121-125.

Ravenholt, R.T. “Tobacco’s Global Death March” Population and Development Review, Vol. 16, No. 2, 1990, pp. 213-240.