by Robert D. Hicks, Ph.D., Director, Mütter Museum,

Historical Medical Library, and Wood Institute for the History of Medicine*

Historians of the book anatomize books for their bindings, printers, paper, illustrators, and consider past readers and cultural contexts. Jorge Luis Borges wrote that a book is “an axis of innumerable relationships.”[i] A current research project has led to an inadvertent discovery and a hypothesis about relationships.

The inadvertent discovery began with my noticing ownership signatures in Civil War-related works and College bookplate data (signifying how books came into the collection). The digital catalogue of the Historical Medical Library does not include information on bookplates or inscriptions written by authors or past owners. I hypothesize that the ownership evidence in the books can re-create the social world of wartime physicians. Three-fourths of approximately 140 Fellows of The College of Physicians of Philadelphia engaged with war work at the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861.

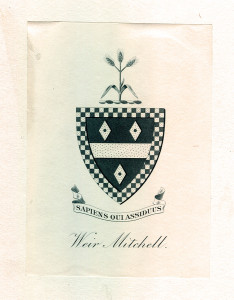

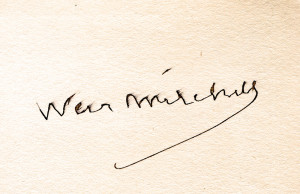

My discovery was a book owned by Silas Weir Mitchell, MD (1829-1914), one of the most colorful, ambitious, famous, and polymathic American physicians of the 19th century and an influential Fellow of the College. Overlooked by scholars among the College’s vast Mitchell holdings is a war memoir by a former army surgeon, John Gardner Perry’s Letters from a Surgeon of the Civil War (compiled by his wife, Martha Derby Perry), published by Little, Brown of Boston in 1906.[ii] The inside front cover bears Mitchell’s bookplate (his name printed as “Weir Mitchell”) with an armorial device and the motto, “sapiens qui assiduous” (roughly, “the wise man is assiduous”) and a library date stamp of February 3, 1913. On the page opposite, the owner signed his name, “Weir Mitchell.”

A contract surgeon during the war, Mitchell worked at several Philadelphia hospitals treating wounded and sick soldiers. With fellow physicians William W. Keen, and George Morehouse, Mitchell founded the country’s first neurology ward at Turner’s Lane Hospital in Philadelphia. When the Gettysburg battle occurred in July, 1863, the army dispatched Mitchell to the scene. Mitchell’s psyche was seared by what he encountered: approximately 27,000 wounded men awaited treatment. When Mitchell began writing fiction in later years, he returned to the war often. At a memorial address following Mitchell’s death, a colleague observed of Mitchell’s writings that “every drop of ink is tinctured with the blood of the Civil War.”[iii]

Years after the war, Mitchell organized an effort to place monuments at all the field hospitals at Gettysburg. At the same time, he apparently acquired Perry’s book. Mitchell’s ownership signature betrays the shakiness and diminishing strength he experienced toward the end of his life. Indeed, the library accession date possibly means that he had begun to dismantle his personal library. While the book itself was not published during the war, its presence in Mitchell’s library attests to his interest in memorializing the work of his fellow physicians. Mitchell was conscious that, with the passing of his generation, without memoirs and memorialization the medical accomplishments of the war might slip from view.

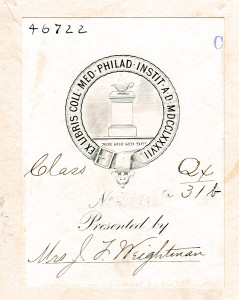

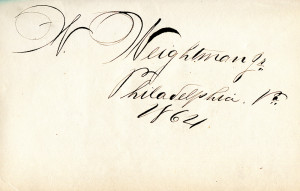

The Perry discovery led to other mysteries. Joseph Carson, MD (1808-1876), Professor of Materia Medica and Therapeutics at the University of Pennsylvania during the Civil War and an influential botanist, wrote Synopsis of the Course of Lectures on Materia Medica and Pharmacy, Delivered in the University of Pennsylvania: with Three Lectures on the Modus Operandi of Medicines. The library has a copy of the third edition, published in Philadelphia by Blanchard and Lea in 1863.[iv] The book contains Carson’s own lectures and must have served many Civil War physicians and apothecaries. The College bookplate notes that the volume was presented to the library by “Mrs. J.F. [T?] Weightman.” Occupying much of the facing page is an ownership signature, “W. Weightman, Jr. Philadelphia, Pa 1864.” The same large signature appears on the inside back cover. Alas, an enterprising librarian in a past century pasted a blue check-out slip on the page facing the inside cover, obscuring some doodling in Weightman’s hand.

At his death, Weightman was reputedly the wealthiest man in Pennsylvania. During the Civil War, as co-owner of the pharmaceutical manufacturing firm, Powers and Weightman (later absorbed into Merck), Weightman might have kept this volume in his office and used it for reference: indeed, several pages bear marginalia and underlining. His obituary in The New York Times for August 26, 1904, states that Weightman was “was often called the ‘quinine King,’ as he was the first man to introduce that drug into this country. He gained much of his wealth while the Civil War was in progress through the sale of quinine, in which he enjoyed a virtual monopoly.”[v] Presumably, the book came into the collection after Weightman’s death. His only immediate family member at his death was his only surviving child, Mrs. Anne M. Wale, who was a partner of the firm. Weightman’s wife, Louisa, predeceased him. So who was the book’s donor? Did Weightman know Dr. Carson or consult him? Further research may illuminate the relationship. Could the book have been used in a laboratory setting? Page 199 (on antacids) shows a round stain from a liquid which bled through several pages.

Dr. Mitchell’s collaborator, William W. Keen (1837-1932), presented to the College one of the library’s two copies of Hand-Book for the Military Surgeon (Cincinnati: Robert Clarke & Co., 1861. Second edition). Although there is no ownership signature, the bookplate states, “Presented by W. W. Keen, M.D.”[vi] For Keen, this book must have been a vade mecum because it outlined the duties of the regimental medical officer, provided templates for all manner of paperwork, and addressed key medical topics from camp hygiene to gunshot wounds to amputations. Keen served on the battlefield as a uniformed doctor, seeing action at the first and second battles of Bull Run (Virginia) and Gettysburg. He also organized military hospitals. Keen must have consulted the book frequently especially in his early military days when he was rarely given direction and referred to himself as “assistant surgeon Verdant Green.”

The Keen book bears a library date stamp of January 10, 1923. Perhaps as with Mitchell, Keen, at this time an elderly man, was making provisions for his personal library and donated the book to the College. How might this work have informed Keen’s war duties? Did he find the case studies too old to be of use? Did he discuss the book with other physicians? Was this particular volume a treasured memento of his war experience?

I now compile ownership information and anticipate creating linkages between wartime physicians, the books they read and used, and physicians’ involvement with the Historical Medical Library and their interest in preserving a wartime legacy. I should heed Saul Bellow, who wrote, “People can lose their lives in libraries. They ought to be warned.”[vii]

Notes

[i] Borges, “Note on (toward) Bernard Shaw,” in Labyrinth: Selected Stories & Other Writings (New York: New Directions, 1964), 213-4.

[ii] Call Number Ef 172.

[iii] Casper Wister. “S. Weir Mitchell, Man of Letters,” in College of Physicians of Philadelphia, S. Weir Mitchell, M.D., L.L.D., F.R.S., 1829-1914: Memorial Addresses and Resolutions. (Philadelphia, 1914), 137.

[iv] Call number Cage Qx 31b.

[v] http://www.brynmawr.edu/cities/archx/04-600/wgh/weightobit.html. Accessed 120815.

[vi] Call number Cage Ef-39a. The book can be read online at: https://archive.org/details/46920340R.nlm.nih.gov

[vii] This quotation appears on many websites without a citation but attributed to Saul Bellow.

*Robert D. Hicks, Ph.D. is the Director of the Mütter Museum, Historical Medical Library, and the Wood Institute for the History of Medicine, as well as the William Maul Measey Chair for the History of Medicine.