– by Patrick Magee, Visitor Services/Gallery Associate

Welcome back to another issue of #MedievalMedicineMonday! On Mondays, Visitor Services/Gallery Associate Patrick Magee will be exploring the depths of medieval medicine as depicted by woodcuts found in our early printed books.

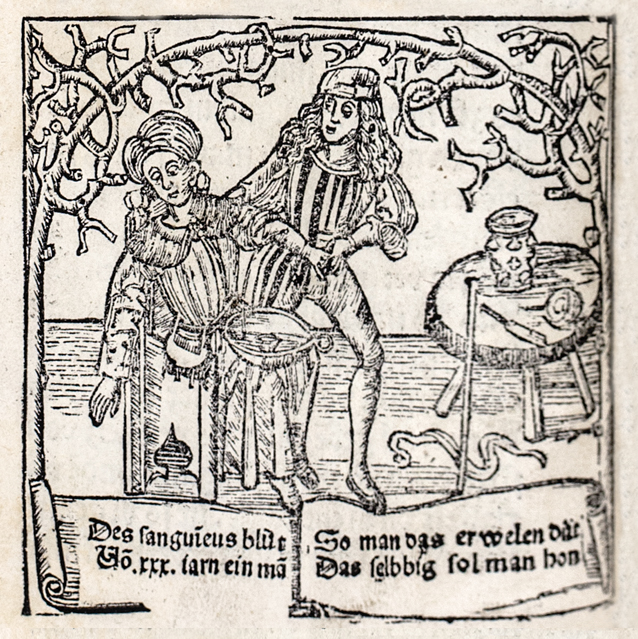

This week, we’re going to look at how woodcut creators and the general public made sense of the beginnings of a plague. In Pestbuch, Hieronymus Brunschwig depicted the onset of a pandemic through a series of woodcuts, themselves serving a purpose somewhere between documentation and warning. In the woodcut drawings, Brunschwig depicts a mixture of illness at its worst alongside the continuing lives of everyday folks and doctors/attenders of the sick.

According to our Digital Image Library description:

Brunschwig’s Pestbuch describes the origin of the plague, its communication, symptoms, prophylaxis and treatment. A surgeon, Brunschwig had witnessed the plague of 1473. Many of the 23 woodcut illustrations are only loosely related to the text, consist of composites, and reappear throughout the text and in other works printed by Gruninger.

Of course, there is quite a bit about medical practice during the 1400s through 1600s that differed from those in modern times. The concepts we use to address something like a pandemic had not been brought into existence or tested yet, and similarly the ideas of what constituted treatment for a malady or illness of any sort were largely experimental. One instance of this many people are familiar with is blood-letting, which is depicted in the below woodcut as a means of removing illness from the body directly. Modern science tells us this doesn’t hold water, but that didn’t stop doctors and barbers alike from trying it at the time. (Miton)

With centuries of medical development behind us, it can be hard to get an understanding of just how long it took for treatments and cures to come to light centuries ago. To put things in perspective, the phenomenon of plagues lasted several centuries before a whole lot could be done other than “wait to die.” In comparison, HPV was discovered around 1983, and vaccination for it is now so standard and readily available that it’s been the subject of commercial campaigns for fifteen-plus years (HPV: The whole story, warts and all).

Historically, religion and science were much more closely tied around the time of the 1473 plague as depicted here. Religion was at the basis of many worldly explanations and actions, and similarly factored in when societal problems had to be faced. Despite many of the woodcuts in this collection being related to the most tangible parts of the illness that you and I can identify, there were also aspects of the plague experienced on a sociocultural level. One of these is depicted in “Divine apparition,” itself depicting what appears to be the greater portion of a town at its collective wit’s end, praying for a higher level of help (Cohen).

It’s important to remember that the era represented in the above woodcuts was one in which religious guidance was often the only blueprint for approaching common problems. The religious informed the secular heavily, and in turn, many ideas we now consider only pseudo-scientific (such as blood-letting) managed to hold water at the time on the grounds of religious sanctity (in this case, a means of removing “impurity”).

In our modern world, we often hear the phrase “the new normal,” although having to make adjustments to wide scale pandemics is nothing new in and of itself. According to Cohen’s “Plague, Print, and the Reformation […],” Germany dealt with plagues roughly once a decade during the period depicted in these woodcuttings. On one hand, this obviously meant that there was immense suffering; however, the circumstances also pushed forward innovations in the dissemination of medical knowledge. Though this era saw its big tech pushes occur through innovations like the printing press, responding to pandemic troubles and through the adaptation of new and emerging technology is certainly a relatable phenomena in 2021 (Cohen).

Sources:

Cohen, Jason E. “Plague, Print, and the Reformation: The German Reform of Healing, 1473–1573. By Erik A. Heinrichs.” (2020): 118-119.

HPV: The whole story, warts and all. (2018, December 18). Retrieved January 16, 2021, from https://scienceblog.cancerresearchuk.org/2014/09/16/hpv-the-whole-story-warts-and-all/.

Miton, Helena, Nicolas Claidière, and Hugo Mercier. “Universal cognitive mechanisms explain the cultural success of bloodletting.” Evolution and Human Behavior 36.4 (2015): 303-312.