– by Wood Institute travel grantee Annemarie Jutel*

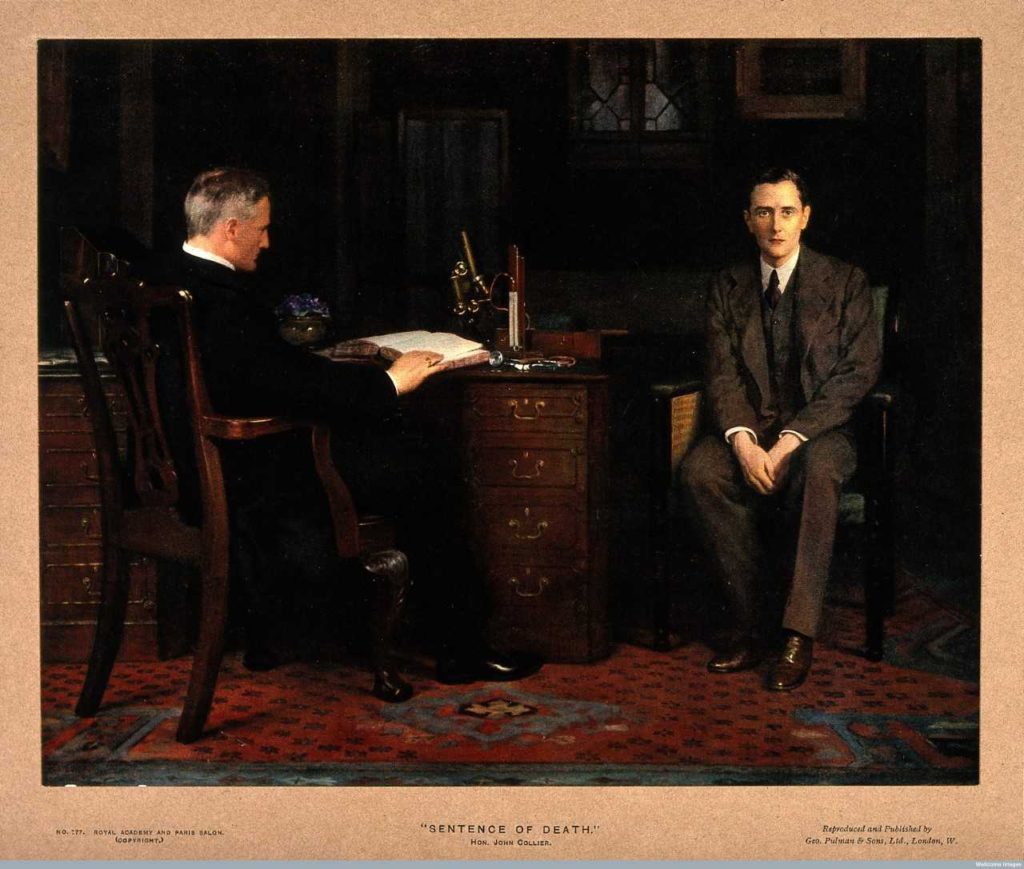

The moment a serious diagnosis is named marks a boundary. As Suzanne Fleischmann wrote: “It serves to divide a life into “before” and “after,” and this division is henceforth superimposed onto every rewrite of the individual’s life story” (p. 10). The power to cleave one’s sense of self in two is what Fleischmann referred to the “transformative power of the diagnosis.” The illustration accompanying this post paints a picture most of us can immediately recognise, so often the power of diagnosis is referred to in popular culture, in medical and patient accounts of illness.

In my just-out book, Diagnosis: Truths and Tales (University of Toronto Press), I juxtapose the now-archived words of doctors from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to those of patients, doctors, novelists, film makers and others of today to explore the power that comes from the act of naming, or receiving the name, for a serious disease. I use historical documents (and notably many held at the Historical Medical Library) in an attempt to underline continuities: values and practices that continue to pervade our beliefs about diagnosis in contemporary society.

John Harrison’s mid-nineteenth century lecture to medical students illustrated how powerful he believed the diagnostic announcement to be.[1] He recommended a serious diagnosis should only ever be made clear to the patient when “death has set his seal on the brow, and placed his iron hand upon the heart, and the physician is called upon by the imploring demands of the patient, be not so cruel as not to deny him his last request, but in the gentlest method, make known to him his real state.”

Some years later, Dr Alfred Schofield explained the power of the physician who had the right to pronounce such serious words “…a doctor is weighed in the balance as no other man [sic] is.” He wrote: “Every act of his, every word he drops, is seed which will surely produce fruit. All he does has a double force.”[2] Dr Joseph Collins maintained that the “the physician soon learns that the art of medicine consists largely in skilfully mixing falsehood and truth in order to provide the patient with an amalgam which will make the metal of life wear and keep men from being poor shrunken things, full of melancholy and indisposition, unpleasing to themselves and to those who love them.”[3]

If we turn to contemporary culture, be it popular or medical, the same transformative power is highlighted. We see films like Still Alice, where the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease transforms the character, and the family around her; like Breaking Bad, where the transformation involves a shedding of moral values to underline the power of diagnosis. Medical text books and writings are replete with protocols designed to soften the blow of a serious diagnosis.

Could we think about diagnosis differently? Must all serious diagnosis be a stake in the heart? From a narrative perspective, one could argue “certainly not!” Narratives don’t always have to promise change. If we hearken back to the Greeks, the dominant narrative form focused on observing what happened to people as they endured trials. The trials were administered by fate, and rather than transforming the characters, they revealed them.[4]

And, as writes philosopher (and woman with a serious diagnosis) Havi Carel, the serious diagnosis offers tremendous potential as well. Michel de Montaigne, the French renaissance philosopher and statesman, wrote that the goal of philosophy was to learn how to face death with equanimity. While our contemporary way of living tends to encourage us to avert our thoughts from the problem of death, a diagnosis provides an opportunity to live reflectively and achieve this philosophical goal. The diagnosis opens us to vulnerability and to dependence, both of which provide us with possibilities for more fully experiencing our life. “Accepting that the human project is towards death, that death structures our life, we are freed up in in our ability to be.” [5]

Endnotes:

[1] Harrison, J. P., MD. (1844). Medical Ethics: A Lecture delivered 23 December 1843 before the Ohio Medical Lyceum. Cincinatti: Enquirer and Message Print.

[2] Schofield, A. T. (1906). Unconscious Therapeutics; or, the personality of the physician. Philadelphia: P. Blakiston’s.

[3] Collins, J. (1927). Should doctors tell the truth? Harper’s Monthly Magazine Harper’s Monthly Magazine, 155, 320-326: 320.

[4] Wilkins, D. (2017). No Hugging, Some Learning: Writing and Personal Change. In E. Perkins & C. Price (Eds.), The Fuse Box: Essays on writing from Victoria University’s International Institute of Modern Letters (pp. 101-121). Wellington: Victoria University Press.

[5] Carel, H. (2015). With Bated Breath: diagnosis of respiratory illness. Perspect Biol Med, 58(1), 53-65. doi:10.1353/pbm.2015.0013

*Annemarie Jutel is Professor of Health in the Graduate School of Nursing, Midwifery, and Health at Victoria University Wellington in New Zealand. She received an F. C. Wood Institute travel grant in July 2018.