– by Kate Grauvogel*

With the isolation of estrogens, androgens, progestins, and insulin in the 1920s and 30s, boundless therapeutic uses for hormones became possible.[i] Fertility control, mental illness, and tuberculosis were just a few of the seemingly disparate problems that researchers attempted to treat or control by regulating hormones. My research adds to this picture by showing just how varied these uses were and how the community of researchers compared and coordinated their efforts. At the Historical Medical Library of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, I discovered additional diverse uses for hormone therapies in the published works of Dr. Edward Strecker and the papers and published works of Dr. Max B. Lurie.

Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) and insulin shock were among the first hormonal therapies. HRT regulated the symptoms of menopause, and insulin therapy was used to treat schizophrenia and psychosis. In addition to using insulin to treat mental illness, Strecker, a Philadelphia psychiatrist, recommended regulating sex hormones to maintain proper emotional function.[ii] His research is outlined in several of his works, including Practical Clinical Psychiatry for Students and Practitioners (1925), which is available at the Historical Medical Library.

I use archival materials like correspondence and notes to show that hormone research sprang from a cohort of researchers and activists who moved in the same social and academic circles. They often collaborated, attended the same conferences, published in the same journals, and used similar experimental methods to demonstrate the effects of steroid hormones.

To introduce this network, I begin with Katharine Dexter McCormick, a biologist, activist, and philanthropist. Aware of the recent application of hormone therapies to treat schizophrenia, McCormick thought they might help her husband, Stanley, who suffered from it. McCormick believed an imbalance of cortisol or a defective gland might be at fault. She enlisted the help of a neuroendocrinologist, Hudson Hoagland, and established the Neuroendocrine Research Foundation in 1927, but withdrew her financial support in 1947 when Stanley died.

Meanwhile, McCormick’s long-time friend, the famous birth control activist Margaret Sanger, became interested in the work of Gregory Pincus, a biologist at the Worcester Institute for Experimental Biology (WIEB) who studied the roles of steroidal hormones in reproduction. Sanger embraced the use of hormones for contraception and asked Pincus to begin working on a hormonal birth control pill. By 1950, McCormick joined forces with Pincus and Sanger, and committed herself to funding the bulk of the research. Deepening this network, Pincus was the colleague of Hoagland, both of whom had worked at the WIEB since 1944.

By 1951, Pincus was hard at work to make the pill a reality. He experimented with four different compounds of progesterone and estrogen in rabbits, mice, and rats before testing it in humans to determine how different doses could prevent pregnancy by suppressing ovulation. Pincus conducted scores of these experiments in the early 1950s and finally published the results in 1956 when his articles on the effects of steroids on reproductive processes, first in animals and then in humans, appeared in Science.[iii] These articles demonstrated the feasibility of regulating ovulation, which was an important milestone in the development of the birth control pill.

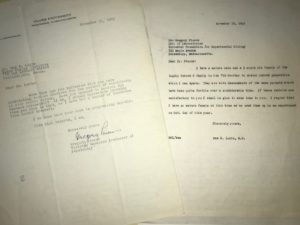

The work of Max B. Lurie reveals yet another direction in hormone research: tuberculosis resistance.[iv] In his correspondence with Pincus, he discussed his research on the effects of steroid hormones in rabbits. In 1951, he published some early results in Science where he found that “the administration of estrogen to susceptible rabbits materially increases their resistance” to tuberculosis.[v] In a 1952 article, Lurie clarified that estrogen and, similarly, cortisol acted by retarding “the dissemination cutaneous tuberculosis and increased the resistance to the disease.” [vi] This means that by prolonging its course, it gave the body a chance to build a more effective immune response. His years of research resulted in a book, Resistance to Tuberculosis: Experimental Studies in Native and Acquired Defense Mechanisms (1964).

Lurie’s work is of great interest in the history of endocrinology and immunology, but has been largely overlooked, perhaps because other treatments for tuberculosis turned out to be more useful. When Lurie began his career in 1921, hormone research was in its infancy but tuberculosis was in full effect, with many sufferers tucked away in sanitariums despite the development of a tuberculosis vaccination that year. By the twilight of his career, applications for hormone research were expanding but tuberculosis was no longer an imminent public health concern in the United States.

Thanks to research undertaken at the Historical Medical Library, I am able to place Lurie alongside Hoagland, McCormick, Pincus, Sanger, Strecker, and others in a larger network of researchers seeking therapeutic uses for hormones in surprisingly disparate areas.

Sources:

[i]Adolf Butenandt and Edward Doisy (working independently) isolated estrone. In 1930 and 1933, two more estrogens, estriol and estradiol, were discovered. Source: Peter Karlson, Adolf Butenandt: Biochemiker, Hormonforscher, Wissenschaftspolitiker (Stuttgart: Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft, 1990).

[ii] E.A. Strecker and B.L. Keyes, “Ovarian Therapy in Involutional Melancholia,” New York Medical Journal 116 (1922): 30., and Strecker, E. A., & Ebaugh, F. G. Practical clinical psychiatry for students and practitioners (Oxford, England: Blakiston, 1925).

[iii] Gregory Pincus et al., “Effects of Certain 19-Nor Steroids on Reproductive Processes in Animals.” Science, 124 (1956): 890-891.

[iv] Max B. Lurie papers, correspondence with Gregory Pincus, box 6, folder 8. College of Physicians of Philadelphia.

[v] Max B. Lurie et al., “Constitutional Factors in Resistance to Infection: The effect of Cortisone on the Pathogenesis of Tuberculosis.” Science, 113, (1951): 234-237.

[vi] Max Lurie, “On the Mechanism of Genetic Resistance to Tuberculosis and Its Mode of Inheritance.” American Journal of Human Genetics 4 (1952): 302–314.

*Kate Grauvogel is a Ph.D. Candidate in the History and Philosophy of Science and Medicine Department at Indiana University-Bloomington and a 2017-2018 research fellow at the Consortium for the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine.