As the medievalists among you probably know, #MedievalMondays has drawn to a close. This new blog series, Seeing is Believing, is one of two that will be taking its place. (Stay tuned next month as Caitlin Angelone, our Reference Librarian and Queen of Pamphlets, introduces you to some of our trade ephemera.)

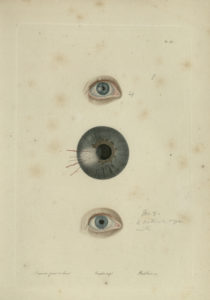

Every other month, I will be scouring our collection for thematically linked material that is interesting to read about but is also interesting to look at. As such, what more fitting topic could be chosen for the inaugural month than the eye, the very vessel of seeing.

Stay tuned to this blog for the introductory post to this month’s topic next Monday 2/2/2018, and follow us on Twitter @CPPHistMedLib where each week this month I will be adding to this brief history of ophthalmology by posting a new image with a link to the full metadata in our Digital Library.