Yes, Virginia, there is such a thing as ‘manuscript waste.’ To us, several hundred years later, it seems a horrible thing. However, it was common practice for early bookbinders to cut up and use pages from unwanted manuscripts as binding material. These pages were sturdy and were used for paste-downs, wrappers (covers), spine-linings, or gathering reinforcements. Not only did the practice essentially recycle texts that were outdated, damaged, or for some other reason, no longer used, it also gives us an opportunity to get a glimpse into the history of a specific text’s use. If we think about it, it’s not too much different than how we treat old newspapers today: as decoupage, potty-training mats for puppies, packing material, etc., etc., etc.

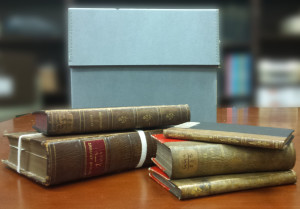

Book bindings

Welcome to this inaugural edition of Fugitive Leaves…

…the blog of the Historical Medical Library of The College of Physicians of Philadelphia (HML). In the tradition of the Transactions and Studies of The College of Physicians of Philadelphia, the blog will highlight the history of medicine and related fields through the work of the scholars we are privileged to host. The blog will also highlight the work of Library staff as well as the unique and wondrous, mundane and ephemeral, aspects of the Library collection, a collection that provides us with endless fascination.

We look forward to your thoughts and comments – the history of medicine is nothing if not a dialogue between what is and what could be. We welcome your participation in that dialogue!

With this inaugural post, we would like to share some exciting news: the HML is home to the largest collection of confirmed anthropodermic books in the country.

This past March the Historical Medical Library (HML) hosted Dr. Richard Hark, the H. George Foster Chair of Chemistry at Juniata College, who came to take minute samples of book bindings purported to be anthropodermic – bound in human skin. Samples were taken, and testing was conducted by Dr. Daniel Kirby, a Conservation Scientist in private practice.

Dr. Kirby used peptide mass fingerprinting (PMF), a method used “to identify mammalian sources of collagen.” PMF does not look at DNA; rather, “enzymatic digestion is used to cleave collagen at specific amino acid sites forming a mixture of peptides. The amino acid sequence of each protein is unique, thus the resultant mixture of peptides is unique.” Drs. Hark and Kirby presented their findings on September 29th at SciX, a conference dedicated “to the analytical sciences, instrumentation and unique applications,” at which they confirmed that the HML is home to five samples of anthropodermic bibliopegy, the largest such confirmed collection in the United States.

The most intriguing aspect of three of these five books is that we not only know who bound the books, but we also know from whom the skin was taken. What follows is the story of Dr. John Stockton Hough and Mary Lynch, a young medical student and a poor Irish immigrant, whose encounter in 1869 led to the creation of the most unique books.

-by Beth Lander, College Librarian

The Skin She Lived In: Anthropodermic Books in the Historical Medical Library

On Wednesday, July 15, 1868, a 28 year old woman named Mary Lynch was admitted to Old Blockley, Philadelphia’s almshouse, officially known as Philadelphia General Hospital (PGH). Old Blockley was located at what is now the intersection of 34th Street and Civic Center Boulevard, on the southeast corner of the University of Pennsylvania. Blockley was where you went when you could not afford care in a private hospital.

The Women’s Receiving Register from PGH lists a small amount of information for each patient: name, birthplace (a country, if other than the United States. Mary was born in Ireland.), age, temperate or intemperate habits (Were you a drunk, or not?), date of admission, ward, color and diagnosis.

Mary suffered from phthitis, an archaic term for tuberculosis of the lungs. Read more…