It’s spring, and that means rhubarb! From strawberry rhubarb pie, to custard, to gin, this vegetable (most often used like a fruit) is either loved or hated by people the world over. Like many plants, rhubarb has been used medicinally for centuries, especially in traditional Chinese medicine. While the various species of rhubarb, and their distribution from Asian countries across the globe have been researched and discussed at length (see Sources and further reading for more), this post will examine the various types of rhubarb and their medicinal uses found in some of the Library’s herbals.

Herbals are books which contain illustrations or prints of plants along with descriptions, traits, and medicinal recipes. Some of the earliest extant written sources about the medicinal values of plants include Sumerian clay tablets (circa 3000 BCE) and the Egyptian Ebers Papyrus (circa 1550 BCE).

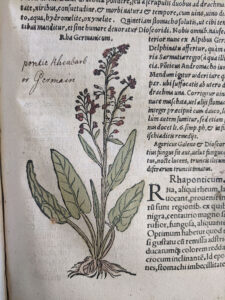

Our first stop in this post is the 1st century CE. Pedanius Dioscorides (circa 40 – 90 CE) was a Greek physician, pharmacologist, botanist, and author of De Materia Medica, a Greek encyclopedia about herbal medicine and related medicinal substances. De Materia Medica was widely read for more than 1,500 years. He was employed as a medic in the Roman army. The Library owns a copy of his works, printed in 1543, and decorated with hand-colored woodcuts.

Dioscorides wrote:

[Rhubarb] is good (taken in a drink) for gaseousness, weakness of the stomach, all types of suffering, convulsions, spleen, liver ailments, inflammation in the kidneys, griping and disorders of the bladder and chest, matters related to hypochondria [indigestion with nervous disorder], afflictions around the womb, sciatica, spitting up blood, asthma, rickets, dysentery, abdominal cavity afflictions, flows of fevers, and bites from poisonous beasts. You must give it…with honeyed wine to those not feverish, but to the feverish give it with honey and water; for tuberculosis with passum [raisin wine]; to the splenetic with vinegar and honey; for gastritis chewed as it is and swallowed down (no moisture taken with it). It takes away bruises and lichen [papular skin disease] rubbed on with vinegar, and it dissipates obstinate inflammations applied with water.

A much later text, Le Grant Herbier, was the first major herbal printed in French. The anonymous text, printed sometime between 1486 and 1488, borrowed 264 of its 474 chapters from an earlier work, Circa instans. In Le Grant Herbier, the medicinal uses of rhubarb differ from those listed by Dioscorides.

The translation here is modernized from the Grete Herball, which is considered the only known English translation and was first printed in 1526:

Against fevers, take the seeds of melons/watermelons/gourds and soak them in water. In the same broth, put cassia fistula [Indian laburnum] and tamarinds, and strain it all. In the strained mixture, steep 2 drams of rhubarb at night, and in the morning, strain it and use it. For pregnant women and older women, steep 6 drams of rhubarb for one night in violet syrup, and give the strained liquid to the patient in the morning. It is also put in syrup for acute fevers.

For the inflammation of the liver and obstruction/blockage of the spleen caused by [unbalanced] humors, take rhubarb with warm water. But it is better to muddle it with a medicine called trifera sarazenica and used with juice of endive.

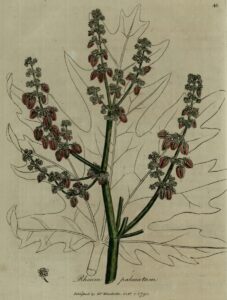

We also find rhubarb included in 19th-century herbals. Medical Botany, William Woodville’s three-volume work of materia medica, was intended to educate medical practitioners about the plants they prescribe and improve upon preceding works by introducing new plants and more detail. Originally published between 1790 and 1793, the 1832 edition includes hand-colored engravings.

Woodville’s description of rhubarb falls more in line with what Dioscorides wrote:

The qualities of this root are that of a gentle purgative, and so gentle that is often inconvenient by reason of the bulk of the dose required, which in adults must be from half a dram to a dram… The purgative quality is accompanied with a bitterness, which is often useful in restoring the tone of the stomach when it has been lost; and for the most part its bitterness makes it fit better on the stomach than many other purgatives do…In cases of diarrhea, when any evacuation is proper, rhubarb has been considered as the most proper means to be employed. I must however remark here, that in many cases of diarrhea, no further evacuation than what is occasioned by the disease is necessary or proper. The use of rhubarb in substance for keeping the belly regular, for which it is frequently employed, is by no means proper, as the astringent quality is ready to undo what the purgative had done; but I have found that the purpose mentioned may be obtained by it, if the rhubarb is chewed in the mouth, and no more is swallowed than what the saliva has dissolved. And I must remark in this way employed it is very useful to dyspeptic persons…The official preparations of this drug are, a watery and a vinous infusion, a simple, and a compound tincture.

But what about today? Do people still use rhubarb medicinally in the 21st century? A Google search for “rhubarb medicine” brings up about 2,290,000 results. WebMD notes: “Rhubarb is used for digestive complaints including constipation, diarrhea, or stomach pain, symptoms of menopause, menstrual cramps (dysmenorrhea), swelling (inflammation) of the pancreas, and many other conditions, but there is no good scientific evidence to support these uses…Rhubarb contains several chemicals which might help heal cold sores and improve movement of the intestines. Some chemicals in rhubarb might reduce swelling. Rhubarb contains fiber that might reduce cholesterol levels.”

Like many botanical remedies with roots in the long history of medicine (pun definitely intended), new scientific research is needed to examine the chemical components of the plant to determine how effective historical medicinal treatments were and whether they can be used effectively today. Several Chinese studies have taken place in the past 20 years to determine the pharmacologically active components of rhubarb (see Sources and further reading for several). And as with all medicines, consult your doctor before starting any new treatments. Luckily, a few slices of strawberry rhubarb pie are most definitely safe!

Sources and further reading

“History of Herbalism.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, May 7, 2021. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_herbalism.

“Rhubarb.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, May 16, 2021. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rhubarb.

“RHUBARB: Overview, Uses, Side Effects, Precautions, Interactions, Dosing and Reviews.” WebMD. WebMD. Accessed May 19, 2021. https://www.webmd.com/vitamins/ai/ingredientmono-214/rhubarb.

Anonymous. “De Reubarbaro. Rewbarbe. Ca. CCC.lxvi.” The grete herball whiche geueth parfyt knowlege and vnderstandyng of all maner of herbes…, circa 1526; Ann Arbor: Early English Books Online Text Creation Partnership, 2011. https://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/eebo2/A03048.0001.001/1:19.5?rgn=div2;view=fulltext.

Cao, Yu-Jie, Zong-Jin Pu, Yu-Ping Tang, Juan Shen, Yan-Yan Chen, An Kang, Gui-Sheng Zhou, and Jin-Ao Duan. “Advances in bio-active constituents, pharmacology and clinical applications of rhubarb.” Chinese Medicine 12, no. 1 (2017): 1-12.

Dioscorides Pedanius, of Anazarbos. Pedanii Dioscoridis Anazarbei De medicinali materia Libri sex. Francoforti, apud Chr. Egenolphum, 1543.

Dioscorides Pedanius, Tess Anne Osbaldeston, and Robert P Wood. 2000. De Materia Medica: Being an Herbal with Many Other Medicinal Materials: Written in Greek in the First Century of the Common Era: A New Indexed Version in Modern English. Johannesburg: IBIDIS. https://archive.org/details/Dioscorides_Materia_Medica/page/n1/mode/2up.

Fu, X. S., Fei Chen, X. H. Liu, Hu Xu, Y. Z. Zhou, and J. Chin. “Progress in research of chemical constituents and pharmacological actions of Rhubarb.” Chinese Journal of New Drugs 20, no. 16 (2011): 1534-1538.

Leech, Caleb. “Regal Rheums.” metmuseum.org, May 28, 2015. https://www.metmuseum.org/blogs/in-season/2015/regal-rheums.

Lo, Vivienne. “Rhubarb.” Mecklenburgh Square Garden. Accessed May 19, 2021. http://mecklenburghsquaregarden.org.uk/rhubarb/.

Regents of the University of Michigan. Middle English Dictionary. 24 April 2013. http://quod.lib.umich.edu/m/med/.

Wang, Jiabo, Huifang Li, Cheng Jin, Yi Qu, and Xiaohe Xiao. “Development and validation of a UPLC method for quality control of rhubarb-based medicine: fast simultaneous determination of five anthraquinone derivatives.” Journal of pharmaceutical and biomedical analysis 47, no. 4-5 (2008): 765-770.

Wang, Xu-mei, Xiao-qi Hou, Yu-qu Zhang, and Yan Li. “Distribution pattern of genuine species of rhubarb as traditional Chinese medicine.” Journal of Medicinal Plants Research 4, no. 18 (2010): 1865-1876.

Woodville, William. Medical botany: containing systematic and general descriptions, with plates of all the medicinal plants….London, J. Bohn, 1832.

Zhang, Hai-Xia, and Man-Cang Liu. “Separation procedures for the pharmacologically active components of rhubarb.” Journal of Chromatography B 812, no. 1-2 (2004): 175-181.