– by Wood Institute travel grantee, Guy Schaffer*

Four years ago, Kathy High and I started an artistic investigation into fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), a medical treatment in which stool from a healthy donor is used to replenish the intestinal microbes of an unhealthy patient. The treatment has been approved for a chronic bacterial infection—C. difficile—and it is currently in clinical trials for inflammatory bowel disease, as well as for illnesses that are only tangentially intestinal: depression, autism, chronic fatigue, Parkinson’s, and others.

Through this engagement with feces, we’ve become curious both about the current culture of fear and control around feces, and the kinds of hope that we see people take on when they talk about FMT. We came to the Historical Medical Library at the College of Physicians of Philadelphia to try to trace a genealogy of our contemporary relationship with feces. In our history of shit, we wanted to probe the annals of proctology to search for different kinds of frameworks for imagining the relationship between feces and health, in the hopes of finding new conceptual tools for exploring the future of shit.

The research has informed an exhibit that was recently on display at the Esther Klein Gallery at the Science Center in Philadelphia, where many of the historical concepts around feces have been incorporated into a biography of a fictional midwife/scientist, Challis Underdue.

I want to share one thread of this history here: ongoing medical efforts to read feces. From ancient times until today, doctors and scientists have been interested in gleaning an understanding of a person’s health or their future through close inspection of excrement.

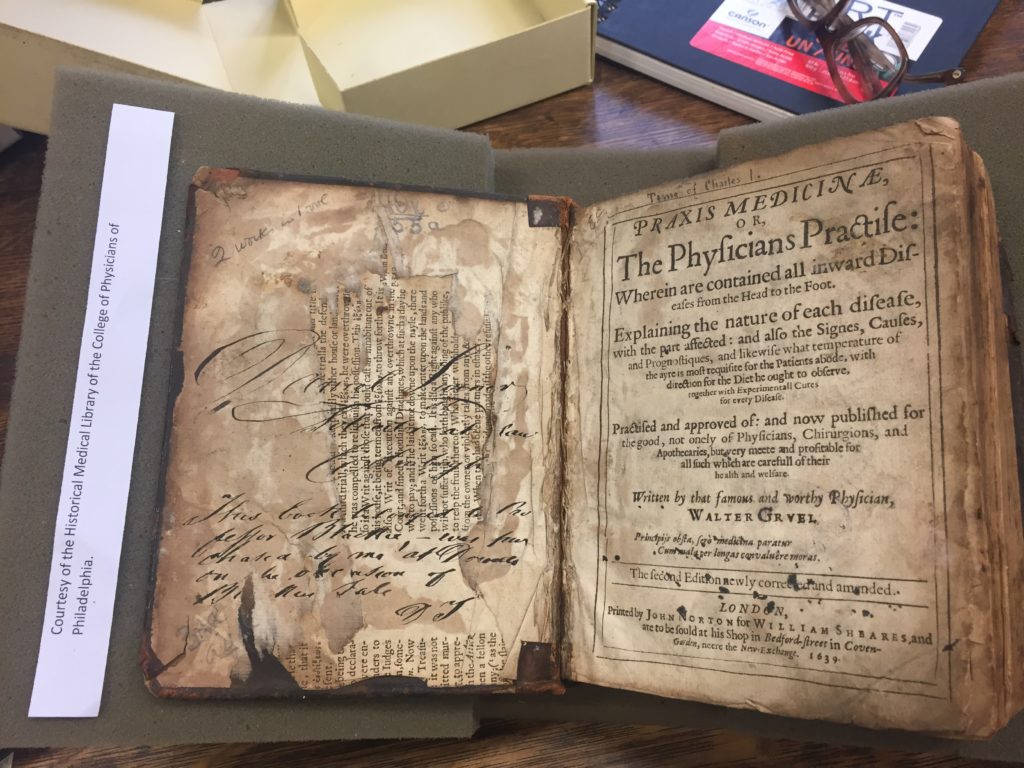

Gualtherus Bruele’s Praxis Medicinae (1639) provides instructions on diagnosing various diseases, often using feces as a tool: “those fluxes are worst, when the excrements doe resemble the colour of a Leeke, and when they be blackish, and doe stink very much,” and “if black excrements be voyded, the body being leane, if parcels of fat and flesh and pieces of the guts be voyded, as also if the patient be weake, the flux is mortall, because the flesh cannot grow together, nor the ulcer be made hard” (300).

Bruele also references some less reputable versions of scatomancy: “Some there bee that are very serious, and are easily persuaded that they have frogs, serpents, or such like in their bowels, whereof some have beene healed, because some such things, unknowne to the patients, were cast into their excrements, when purging medicines were ministered” (34).

Du Four de la Crispiliere’s Commentaires en vers francoid, sur l’ecole de salerne, published in 1671, includes a chapter on “scatomantie.” He clearly feels a need to defend the practice; he references an instance in which Aristophanes calls the Galenic doctors “scatophagous” (eaters of scat) and explains that they only looked at human feces, and sometimes prescribed treatments that included animal feces, but usually in very small portions.

De la Crispiliere provides a classification of the various types of feces, based on consistently, quantity, color, odor, texture, and the presence of worms. He describes a “commendable excrement,” it “should be soft like honey, well assembled, and holding together, of yellowish color, in proportion to the food you ate.” There are a variety of more threatening symptoms that can appear in the excrement: “fatty feces is deadly, because it means the body is liquefying itself,” or “Black excrement at the beginning of a disease is always bad.”

The Commentaires are also notable for their advice on how to defecate. The majority of the text is dedicated to basic daily health rules, like what to eat, but it includes a guide to using the toilet as well:

| Ne te retiens point fortement

Quand il faut aller a la selle Cela blesse le fondement Et la faculte naturelle Les excrements dans les boyaux Durificans comme des noyaux Gesnent l’homme autant qu’une bete Et par leurs malignes vapeurs Qui s’elevent justqu’a la teste Ils luy causent mille douleurs |

Don’t hold on tight

When you need to go to the saddle That hurts the foundation And the natural faculty The excrement in the bowels Will harden like nuts Annoying the man like a beast And by their evil vapors That rise up to the head They can cause a thousand pains |

We might also understand David MacBride’s fermentation experiments as part of a broader coprological project. In a series of experiments recorded in his Experimental essays on medical and philosophical subjects (1767), he attempted to understand how food is transformed into excrement in the human body: “…that different combination, of the insensible parts of the alimentary substances which enable the immense variety of discordant mixtures that enter the composition of our food, to depart so far from their original natures as to become one mild, sweet, and nutritious fluid; for this demands a great deal more than mere mechanical mixtures and dissolution, which is the most that the common theories of digestion extend to…” (3).

In contrast to the dominant mechanical model of digestion, MacBride suggests that digestion is a kind of fermentation, in which the substance of food was transformed, giving off a subtile vapor (presumably carbon dioxide or methane). In order to compare these two processes, he places a variety of different foodstuffs in vials, and places these vials in a sand bath, as a simulation of digestion. He observes that the food “raises a fermentation” and, in a series of tables, describes the sweet or putrid smells that obtain from different combinations of food.

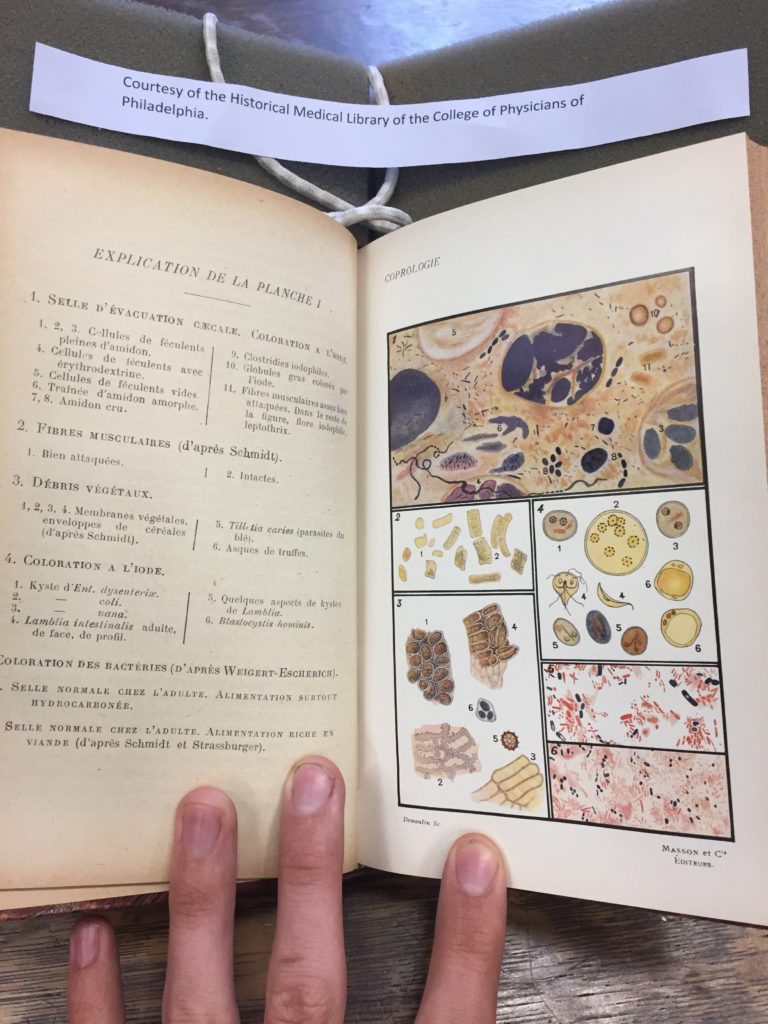

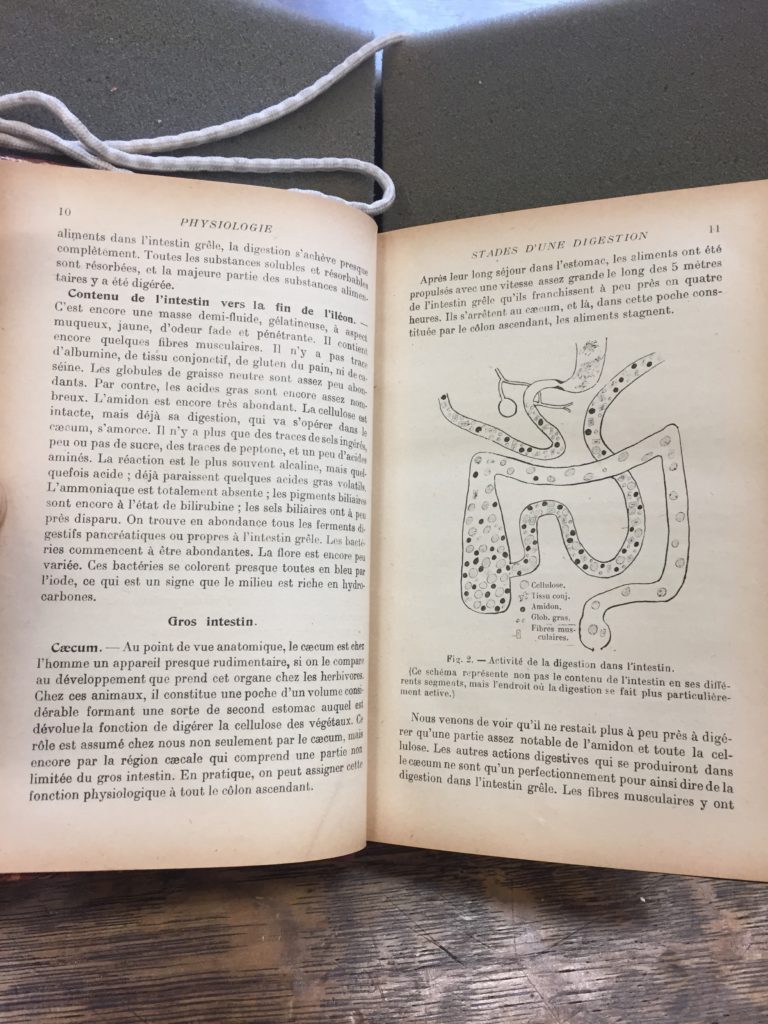

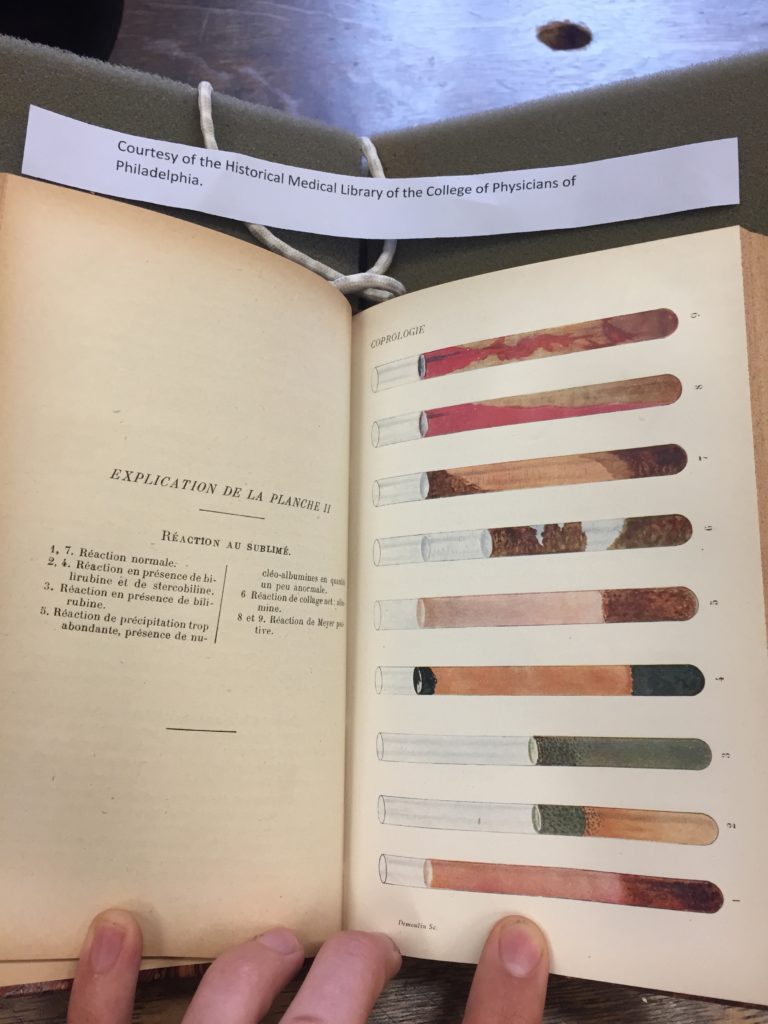

R. Goiffon’s Manuel de Coprologie Clinique (1921) lets us see a more systematic coprology, which explains not just how different qualities of feces relate to different conditions, but how the different stages in the formation of feces can reflect those conditions. The quality of feces is based on an interaction of three factors: the travel of food through the digestive tract, the action of the intestinal microflora, and the inflammatory products of the mucosa. Using microscopic analysis, Goiffon is able to identify structural and biological elements of feces that can indicate problems at different stages of the digestive process. For instance, an excess of pectin and connective tissue in the feces can indicate a deficiency in gastric acid. Goiffon provides loving illustrations of all the substances he looks for in a coprological assessment—it is worth checking out the Manuel de Coprologie Clinique for the visuals alone.

*Guy Schaffer is an Adjunct Instructor in Science and Technology Studies at the New Jersey Institute of Technology . He received an F.C. Wood Institute Travel Grant from the College of Physicians of Philadelphia in 2017.