– by Ph.D. candidate Mary Mahoney*

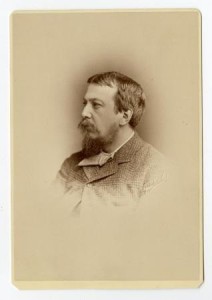

My dissertation focuses on the history of bibliotherapy, or the use of books as medicine. I recently travelled to the College of Physicians to examine the papers of Dr. S. Weir Mitchell, a physician perhaps best known for his invention of the “rest cure” to treat neurasthenia. While Mitchell certainly believed in the therapeutic value of reading in his own life – both reading and writing fiction throughout his career – his reputation has been shaped inexorably by his belief in the therapeutic value of restricting reading as a form of medicine. Neurasthenia was a disease that manifested itself in symptoms that affected the mind and body, including headaches, depression, numb limbs and exhaustion. While Mitchell genuinely believed that restricting reading was vital to resting the body and returning it to health, his female patients felt deprived because reading was a vital part of their lives.

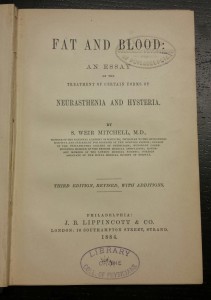

Reading was an act that S. Weir Mitchell understood in bodily terms. Writing in Fat and Blood, his foundational work on the rest cure, he wrote about reading as an act that proved dangerous for bodies suffering from nervous exhaustion. Reading posed a threat for both the strain it placed on a reader’s eyes and the energy it drew from the body. A case study from Fat and Blood details these dangers.

“Mrs. C” was thirty-three when she came under Dr. Mitchell’s care, and presented a textbook case of neurasthenia. Her trouble began, according to his account, when at sixteen she completed a “severe course of mental labor,” by finishing a four-year school program in two years. This was quickly followed by an early marriage, three pregnancies and mounting exhaustion that resulted in a “loss of flesh and color.” “Everything wearied her,” Mitchell wrote in his account of her illness, “to eat, to drive, to read, to sew.” “Mrs. C” developed asthenopia, or eyestrain, which ultimately led to her breakdown. The significance of eyestrain for her life, and most importantly for her life as a reader, proved the final straw. “The athenopia which is almost constantly seen in such cases added to her trials, because reading had to be abandoned, and so at last,” Mitchell concluded, “despite usual vigor of character, she gave way to utter despair, and became at times emotional and morbid in her views of life.” To treat her, Mitchell prescribed a total restriction of reading and writing, a strict diet and seclusion from family and friends. After two months, and forty pounds gained, he pronounced her cured.[i]

In the years since his death, S. Weir Mitchell’s rest cure has become a symbol of attempts by male physicians to control women in the name of health, an argument forever immortalized in Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s The Yellow Wall-Paper (1892). Mitchell’s papers reveal that he corresponded with many women whom he once treated and considered lifelong friends. In offering advice to treat their neurasthenic symptoms, as historian David Schuster has noted, Mitchell even suggested reading and painting as appropriate forms of recreation.[ii] So how can we explain the negative connotations surrounding Mitchell’s therapeutic restriction of reading? In part, I argue, his reputation has been shaped by the records of women treated at his hands or under the care of physicians inspired by his hugely influential cure. Jane Addams, the famous social reformer who founded Hull-House, reflected at the end of her life on the rest cure she was prescribed in 1882. Remarking on the complete restriction from reading that was central to her “cure,” “I have come to the time when I could not read,” she wrote, “and then found how much I had depended on that.”[iii]

I wanted to utilize Mitchell’s correspondence with female friends, patients, and readers to examine different ways of thinking about books, reading and health in order to contextualize this divide between Mitchell and critics of his cure.

Mitchell was an avid reader, and his correspondence with Amelia Gere Mason is emblematic of his life as a reader. The language he used to discuss books was often sensory. Writing to Mason, who was a friend and a patient, Mitchell framed his dislike for a book in sensory terms. “I remember when reading one of the books of this man (whom I shall never read again) that amidst an exquisite passage I came upon something which was to me like the sudden sensation of Limburger cheese in a rose garden. You have the happy faculty of picking out the best and ignoring the worst,” Mitchell said complimenting Mason on her reading habits. “Books like this I would rather not read at all, on the whole.”[iv] Rather than reading past sentences that did not please him and focusing on parts of novels he did enjoy, Mitchell desired the power to “morally disinfect” sentences that offended him.[v] In a later letter to Mason, he agreed with her critique of modern fiction for its lack of morals, declaring himself “happy that I never wrote a line that a girl might not read.” [vi]

Mitchell’s papers show that he also disliked books that favored too much introspection. In one letter to Mason, he critiqued Henry James’ novels for their analysis, writing “immense analysis seems unnatural to me.”[vii] Mitchell’s distaste for introspection and analysis extended into his medical practice, and he credited introspection for making women’s neurasthenic symptoms worse.[viii] Too much analysis of one’s self was dangerous.

Many of his patients desired books that inspired introspection, however. This is evident in a fan letter Mitchell received from a woman who loved Constance Trescott, Mitchell’s novel about a nervous woman who sets out to avenge her husband’s murder. For this reader, Mitchell’s novel helped to affirm her own choices in life. “If it hadn’t been for you and your books,” she wrote, “I think I should have married the wrong man just because he had lots of money.” Showing the ways readers imagine a relationship with favorite authors, she added, “Do you mind my confiding in you so? You see I don’t know you but I know you won’t tell and that is a comfort.”[ix] For this reader, Mitchell’s novel and the friendship she imagined with him offered affirmation of her choices and the comfort of an imagined friend. We might imagine how devastating the absence of this outlet would be for some of Mitchell’s patients, even as Mitchell sincerely believed restricting reading was essential to heal an exhausted body.

These multiple perspectives of reading as a matter of mind, body, and self-help complicate Mitchell’s own professional assessments of reading. The “Mrs. C.” story, which, at face value, tells of the potential of reading to strain the eyes, might reveal more than the textbook case he intended, for example. Instead of reading of her trials as an exemplar of the triumph of the rest cure, we might also read her illness as a testament to the vitality of reading to her health. As Mitchell details, it was when she had to abandon reading that “at last…despite usual vigor of character, she gave way to utter despair, and became at times emotional and morbid in her views of life.” [x] While Mitchell may have sincerely believed that by restricting reading he was restoring his patients to health, in so doing he may have been blind to the dangers of depriving his patients of a vital means of consolation, escape and identify formation. What may have been medicine for the body, I argue, could simultaneously be poison to the self.

Endnotes

[i] Mitchell, S. Weir. Fat and Blood: An Essay on the Treatment of Certain Forms of Neurasthenia and Hysteria. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1891 (sixth edition) 123-126.

[ii] Schuster, David G. “Personalizing Illness and Modernity: S. Weir Mitchell, Literary Women, and Neurasthenia, 1870-1914.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 79 (2005): 695-722.

[iii] Jane Addams quoted in Poirier, Suzanne. “The Weir Mitchell Rest Cure: Doctors and Patients.” Women’s Studies 10 (1983): 24.

[iv] S. Weir Mitchell to Amelia Gere Mason 4 January 1912, MSS 2/0241-03, series 4.3, box 7, folder 3.

[v] Ibid.

[vi] Mitchell to Amelia Gere Mason 23 September 1912, MSS 2/0241-03, series 4.3, box 7.

[vii] Mitchell to Amelia Gere Mason. 8 September 1908, MSS 2/0241-03, series 4.3, box 7.

[viii] Mitchell, Fat and Blood, 158.

[ix] Mary Pope Paddon to S. Weir Mitchell. 29 June 1905. MSS 2/0241-03, series 4.4, box 11, folder 25.

[x] Mitchell, Fat and Blood, 123-124.

*Mary Mahoney is a Ph.D. candidate in History at the University of Connecticut.