– by Wood Institute travel grantee Ryan Habermeyer*

Several years ago, in a daze of dissertation research, I stumbled upon a passing comment by William Osler, pioneer of modern medicine: “To talk of diseases is a sort of Arabian Nights entertainment.” What a curious coupling, fairy tales and medicine. As much as I tried to forget it and press forward with my dissertation I kept returning to that idea. How is pathology a bedfellow to fairy tales?

Here is my best conclusion: For centuries, disease was almost indistinguishable from magic – spontaneous, metamorphic, at times exotic, powerful, and mysterious. For centuries, disease provoked both wonder and fear; it elicited a kind of grotesque enchantment. Disease, I like to think Osler is suggesting, tells a story. It has traceable beginnings, chaotic middles and dramatic ends. To us, the victims, it is the villain which must be vanquished; but I imagine if diseases could talk they would cast themselves as the heroes and heroines struggling to survive against impossible odds.

Comments like Osler’s speak to me because I am admittedly something of an odd academic specimen. I am neither physician nor historian nor literary theorist nor medical researcher. I teach creative writing. I write fiction. Speculative, weird, absurdist fiction. Imagine Bruno Schulz, Italo Calvino, Ludmilla Petrushevskaya, and Kurt Vonnegut got together with the Brothers Grimm and had an illegitimate love child. After publishing my debut short story collection, The Science of Lost Futures—a book that explores the intersections of history and folklore, science and magic, the human and inhuman—I wanted to attempt something different. True, that book has stories about a woman collapsing into the black hole growing on her shoulder, a family that adopts a former Nazi as a pet, and a woman who discovers one morning her womb as fallen out; but yes, I wanted to do something very different.

I started drafting sketches, anecdotes and vignettes all circulating around Osler’s idea of the entanglement of medicine and fairy tale. But as these fragments evolved into a novel I found the medium of the storytelling needed a peculiar form. It has since morphed into a satirical fin de siècle medical encyclopedia of sorts and tells the story of a family of physicians wrestling with questions of medicine, race and religion through various case studies, letters, pharmaceutical recipes, scrapbooks and miscellaneous medical notes. Such experimentation was fun but problematic. How to create an authentic-looking encyclopedic novel that successfully captures the look and feel, as well as the style and tone and voice of late-Victorian medical ephemera? And where to begin researching such a strange novel?

For a novice in the history of medicine, the Historical Medical Library and the Mütter Museum at the College of Physicians of Philadelphia seemed an obvious choice.

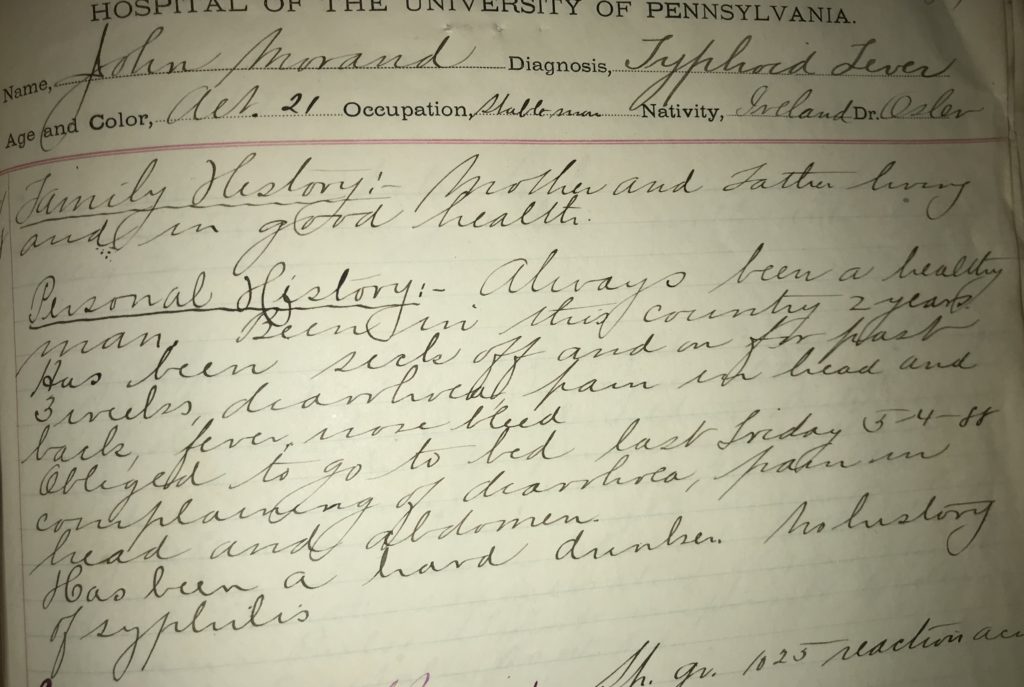

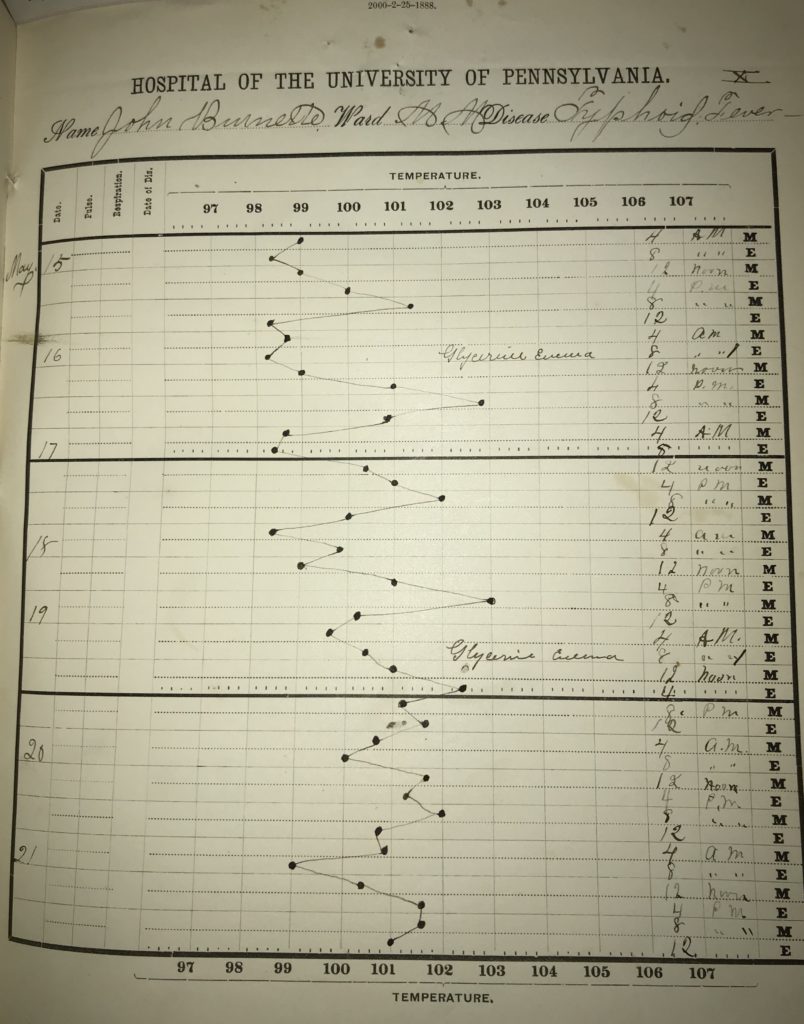

I hoped to discover in the archival collections an archaic medical jargon and stylized vocabulary; a medical dialect of sorts. Once more, William Osler did not disappoint. His massive casebook of patient visits was full of idioms and observations as strange and poetic as anything in Grimms’ tales. There he prescribes “a gargle of witch hazel” for sore throats, diagnoses gastrointestinal distress by making “a percussion over the abdomen,” chastises a patient for being a “worshipper of Bacchus” and philosophically ponders how a man was asphyxiated by “illuminated water.” The terse prose with its detached scientific nonchalance is both comedic and horrific, often simultaneously so. How else to describe chloroform drops prescribed for an ankle sprain, or a soap suds enema with turpentine to cure irregular bowel movements? Sadly, physicians no longer recommend that men soak their penises in boiling milk for fifteen minutes to cure gonorrhea. But Osler did.

Unbeknownst to him, Osler’s mundane patient records had cataloged a rich repository of that most nebulous and elusive element of fictional craft: voice. That intangible thing that makes a story feel authentic, palpable, come alive.

Had I only examined Osler’s casebook, my visit would have been worthwhile. But I was delighted to discover the intersections of folklore and (pseudo)science manifesting in pharmaceutical recipe books by George B. Green, John Ecky, and John Dauntesey. Asthmatic elixirs, electrobiology therapies, herbal poultices, arsenic tinctures, and a splendid cure for hydrophobia involving pulverized oyster shells are a few of the fascinating portraits of alchemical echoes in pre-modern medicine. As is Charles Asher Knight’s casebook, which records multiple accounts of maternal impression, a medieval theory that mental, emotional or physical stimuli on the mother imprints on the developing fetus in the form of defects or disorders. In one particularly rich encounter, Knight recalls a pregnant patient looking out a window when suddenly surprised by a bee that lands on her nose and dances there for a moment before flying away. Her child, Knight observes, is born with a small divot on the tip of its nose, as if pricked with a bee stinger. I am confident such an episode will find its way into my novel.

Many of the casebook entries have the poetic compression of a folktale and end just as abruptly with an equally disconcerting ambiguity that borders on poetry. Page after page patients arrive, hemorrhaging blood from the bowels or suffering from vertigo “wrought by an extra-marital affair with a younger man” or “drowned in a sea of melancholia.” One woman visits Osler after experiencing “womb trouble” and describes symptoms which Osler does not appear to recognize as ovarian cancer. He prescribes her a tonic and sends her on her way. What happened to them, these diseased pilgrims? Such entries remind me of the Russian short story master Anton Chekhov who, in his letters on fictional craft, stated that the only proper way to end a story was to return characters to “the open destiny of life.” Other times the ambiguities are of a more humorous flavor. “Removed imbedded speck from left eye to relieve conjunctivitis. Removed with knife under cocaine,” Osler writes. Does that mean he anesthetized the patient with cocaine, or himself? I guess we will never know, and that is part of its magic.

Any lingering doubts about coupling medicine and fairy tale into fiction were emphatically laid to rest by the “Grimm’s Anatomy: Magic and Medicine” exhibit in the main gallery of the Mütter Museum. Curated by Anna Dhody and Linda J. Lee, this marvelous exhibit does with images and objects what I hope to accomplish with words. With any luck, my novel will not just medicalize the fairy tale but fairytale-ize turn of the century medicine.

*Ryan Habermeyer is an Assistant Professor in the Department of English at Salisbury University. He received an F.C. Wood Institute Travel Grant from the College of Physicians of Philadelphia in June 2018.

Too bad it’s too late to submit this to the annual American Osler Society’s annual meeting. It’s fascinating. We are big fans of Osler’s here at the Medical & Chirurgical Faculty of Maryland. Check out our blog, The MedChi Archives.