– by Wood Institute travel grantee Madeline Hodgman*

I came to the Historical Medical Library at the College of Physicians of Philadelphia in July 2016 to research the American Social Hygiene Association for my senior honors thesis at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. My thesis explores the development of sex education in American society throughout the 20th century, comparing and contrasting both comprehensive and abstinence-only curricula. I learned through my work at the Library that “social hygiene” rhetoric not only referred to the public health epidemic of sexually transmitted diseases, but was also used as coded language to mask a eugenics agenda. This presented an interesting contradiction to my research — not only was the social hygiene movement one of the first comprehensive sex education campaigns for public health, but it was also actively encouraging abstinence in terms of eugenic “fitness” for procreation.

In 1905, Dr. Prince Morrow, a dermatologist, founded the Society of Sanitary and Moral Prophylaxis in New York City, to emphasize the public health risk of those same social problems opposed by Anthony Comstock and company.[1] The Society consisted of Morrow’s fellow doctors and medical professionals, all of whom believed that in an ideal world, sex education would take place at home at the discretion of the parents — a task that most parents were hardly qualified to do. Thus, Morrow argued that the responsibility should fall to medical practitioners, an idea that was supported by prominent social reformers like Jane Addams. Though they may have stemmed from an anti-vice perspective, Morrow and the Society were concerned with a wide range of reproductive issues for which adequate sex education was a much-needed remedy.

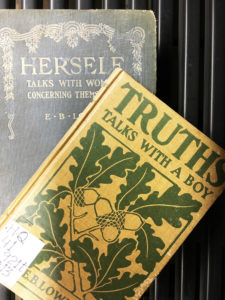

Morrow is considered by historians to be one of the first activists who initiated the push for public school sex education in the United States. At this time, doctors were an individual’s primary point of contact about sex, and as such, much of the information a young person received came from anatomical diagrams and medical jargon. The National Education Association endorsed Morrow’s Society for Moral Prophylaxis in 1912, and further encouraged the adoption of sex education courses in schools.[2] This challenged the status quo of sex education by extending beyond public health campaigns to reach younger Americans, and can be considered a turning point in its history. From this point on, one of the main aims of sex education would be to prepare young people for adulthood.

While Morrow set the wheels in motion for the shift from private sex education to public, his real success was in popularizing the idea of encouraging youth abstinence. Reformers’ hopes for the mid-1910s was that, by educating young people about sexuality, such people would choose abstinence. Not only was this to prevent out-of-wedlock births, but it also fell in line with the eugenic idea of “fitness” to marry and procreate. Many adults subscribed to the notion that a commitment to abstinence and purity were indicative of one’s social class and other salient social identities, which, in turn, indicated superiority.

In 1908, the Society of Sanitary and Moral Prophylaxis was endorsed by the American Purity Alliance, a like-minded organization, though with a narrower focus on abstinence from sexual intimacy outside of a monogamous, heterosexual marriage.[3] Furthermore, in 1911, the American Vigilance Association, dedicated to “fighting prostitution [and]…educating the young about the dangers of immorality,” merged with the Society, hoping to use Morrow’s prestige as a physician and activist to spread their message as well.[4] By the time of his death in 1913, Morrow’s mission had extended from halting the spread of disease to indoctrinating young people with the ideals of their elders. The organization was re-branded as the American Social Hygiene Association (ASHA) that year, to commemorate the merging of the medical and purity communities toward a common goal.[5]

The social hygiene movement had a unique impact on sex education in several ways. For one, Dr. Morrow and ASHA took a proactive role in encouraging the transition from physician-taught sex education to school-based initiatives. Not only did this facilitate a shift from private sex education to public, but this initiative was notable also for its support of concise and factual curriculum, a step away from the highly metaphorical and ambiguous “facts of life” chats before. However, these efforts were not without flaws — the explicitly racist language and policies of this movement alienated and under-served immigrants and people of color, which significantly underscored an otherwise forward-thinking campaign.

[1] “The Development of Sexology in the USA in the Earlier Twentieth Century,” in Sexual Knowledge, Sexual Science: The History of Attitudes to Sexuality, ed. Roy Porter and Mikuláš Teich, by Vern L. Bullough (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 305.

[2] David Campos, Sex, Youth, and Sex Education: A Reference Handbook (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2002), 60.

[3] Bullough, Sexual Knowledge, 305.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

*Madeline Hodgman earned her Bachelor of Arts in History in 2016 from the University of Massachusetts Amherst. She received an F.C. Wood Institute Travel Grant from the College of Physicians of Philadelphia in 2016.