It’s hard not to have favorites when working in a special collections setting. While searching through our incunabula, I found one bound in a manuscript that I had not seen previously. This particular wrapper has now become one of my favorite items in the collection, and one that I intend to continue researching when time and other duties allow.

In my initial giddiness at finding yet another manuscript binding, and a cursory glance at the script (and illumination!), I really hoped that I had found a fragment of an Anglo-Saxon manuscript. After correspondence with Michelle P. Brown and Peter Kidd (and some studying), however, I had to admit that’s not what this manuscript was.

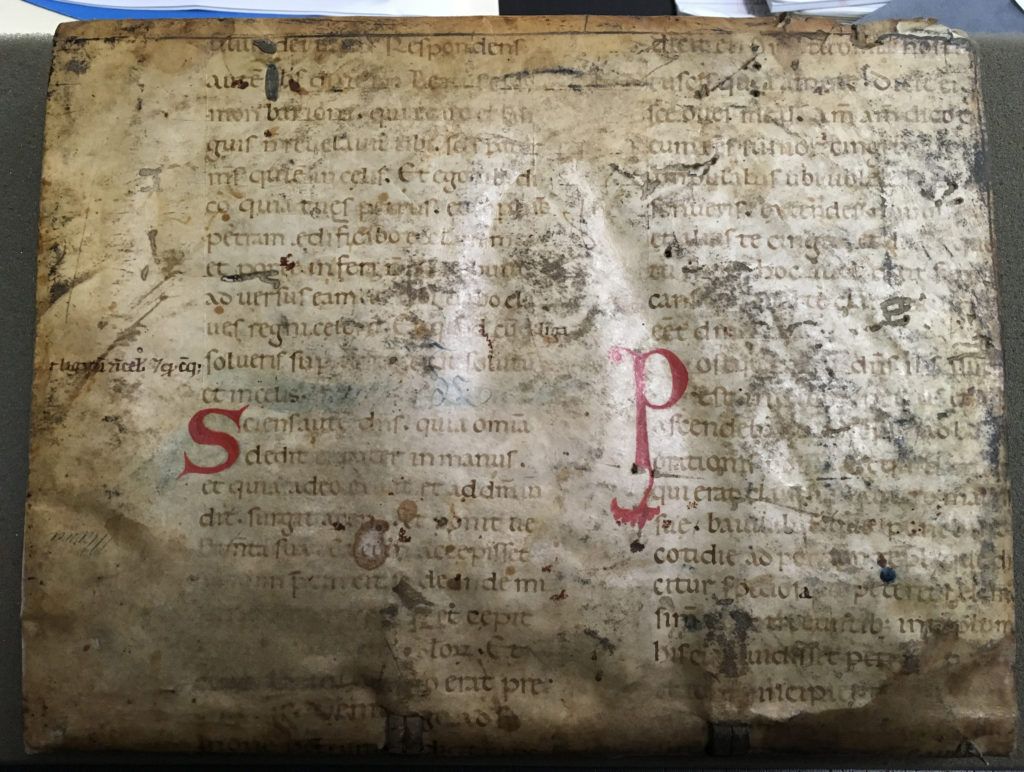

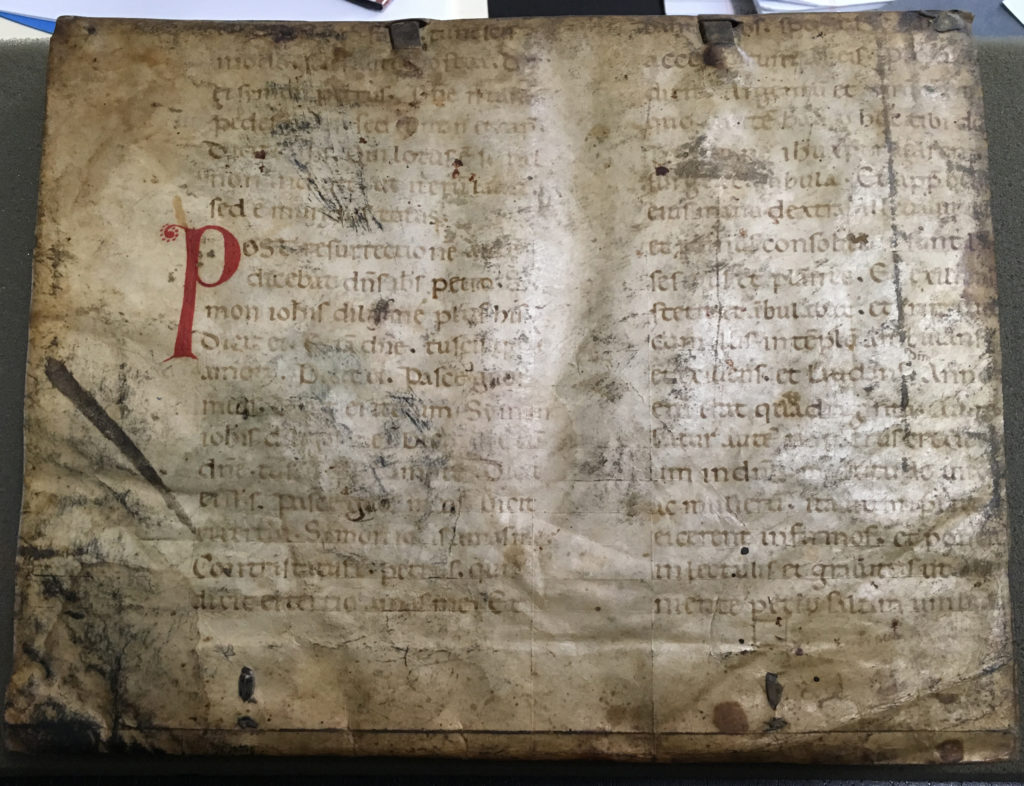

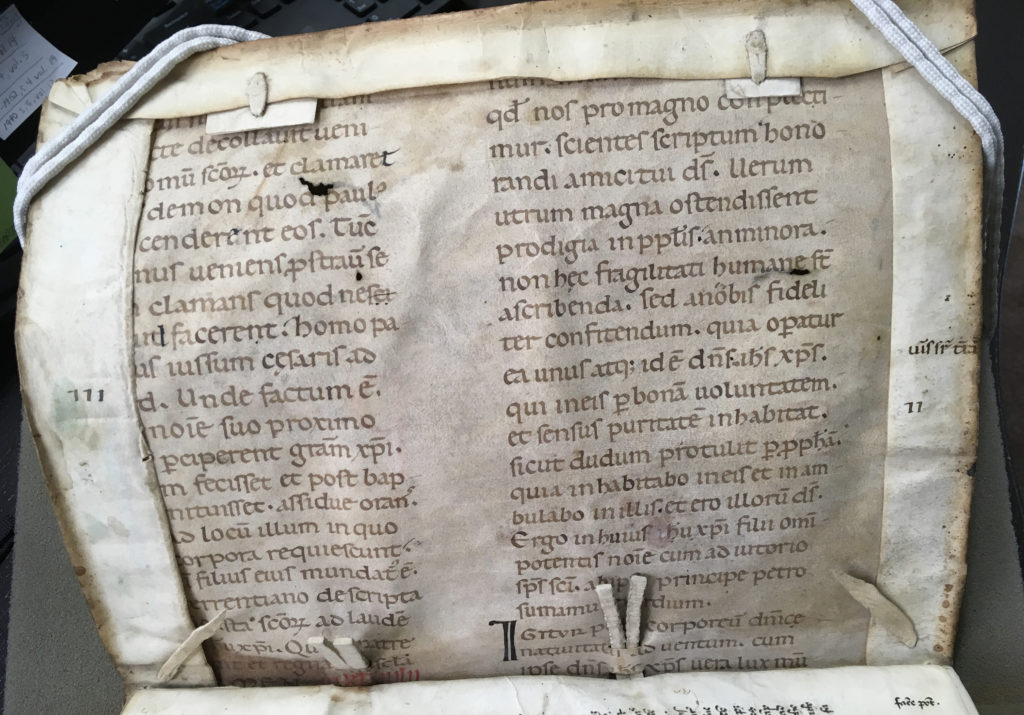

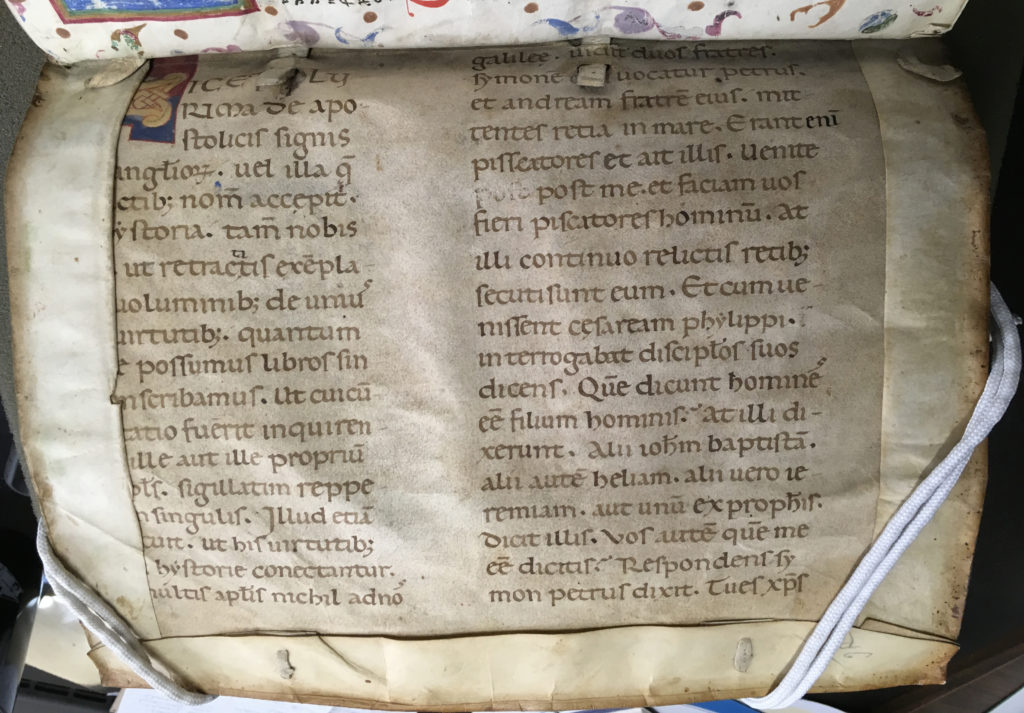

The script itself is a Caroline miniscule, written below top-line, and while some of the feet of the serifs (check out the m’s and n’s) look a bit English, it does have that Italianate roundness to the letters. The darker ink used for some corrections also appears to have been used for the I in Igitur (recto, column b, line 22). [n.b. The inside of the wrapper is the recto of the leaf.] There are 3 rubricated initials as well, all on the verso.

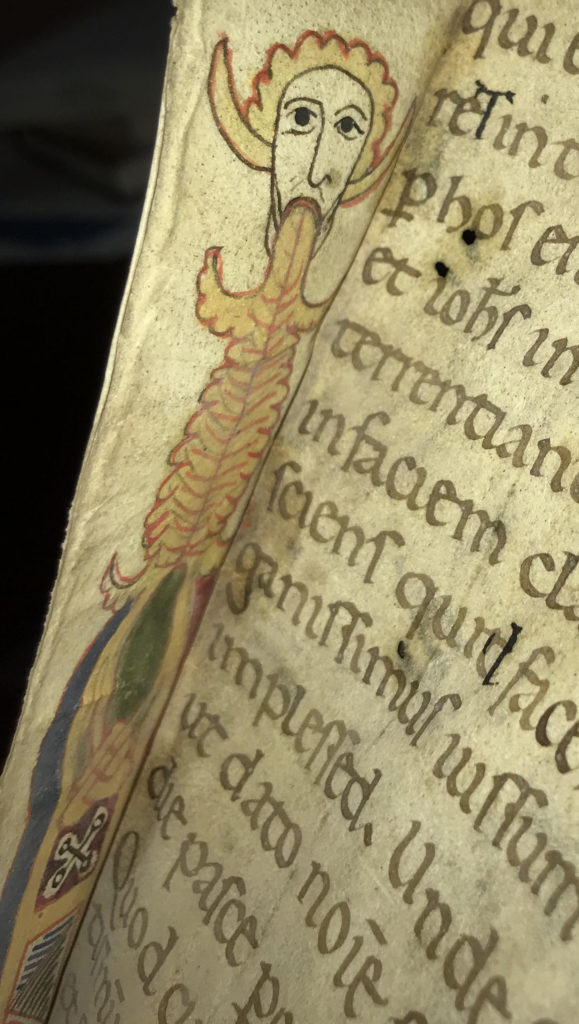

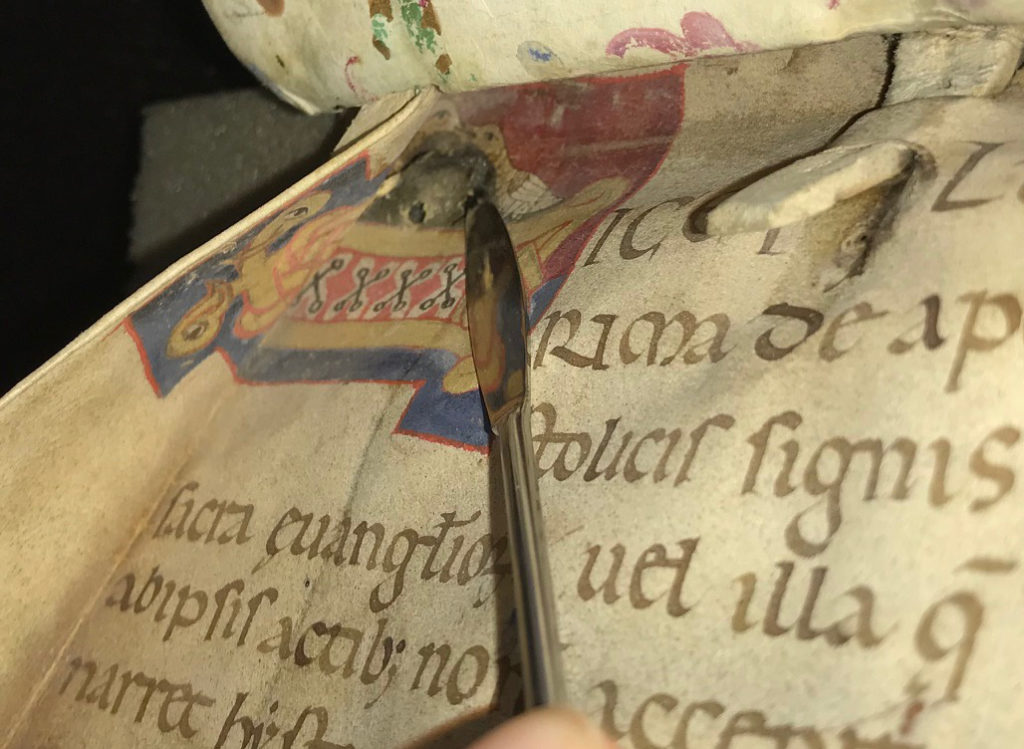

My favorite part of the leaf is the beautiful 24-line painted initial L (recto, column a). Its ascender is topped with a man with curly? yellow hair, who is spitting the letter out of his mouth, beginning with some yellow foliate. The left border is blue; the right red; both run the length of the initial and surround green and yellow interlacing above alternating blue, green and red triangles filled in with diagonal stripes. The ‘foot’ of the L is on a red and blue background, with yellow interlacing and eyes surrounding 3 black X’s on a red background. There are two birds on top of the ‘foot’ – perhaps one is feeding the other (?) – on a green background. Michelle Brown has suggested that the birds might be a “bird in a nest eg pelican in her piety perhaps?…”

So what about the content of the text? Here’s where it begins to get (even more) interesting. The leaf contains two discreet texts: the first being the entry for 26 June from Ado Viennensis’ Martyrologium; the second, “Virtutes Petri” from the Virtutes apolostorum. Although the entry from the Martyrologium is for 26 June – the day on which Saints John and Paul were martyred – the scribe omits (or skips?) the entries for 27 (the martyrdom of Crescens, a disciple of Paul) and 28 June (the vigil of Saints Peter and Paul), but notes in red ink that 29 June is the feast of Saints Peter and Paul. My guesses about this are that 1) Crescens was not a celebrated saint in the area in which the manuscript was created; 2) the scribe did not believe it was important to mark a vigil (as probably most people knew the vigil was always the day before the feast); and 3) that the previous hagiography may have been Paul’s, as he features in both the 26 June entry and the scribe’s note.

Here’s a layout of the text:

Column a, lines 1-25

- Kal. Julii [26 June], Martyrologium, Ado Viennensis; beginning with “…confitentes sacra passionem eorum. Ita ut unicus filius terrentiam qui eos nocte decollauit ueni retin tra domini sanctorum…”

Column a, line 26 – Column b, line 20

Prologue to Virtutes Petri from Virtutes apostolorum

Column b, lines 21-44 – verso

Virtutes Petri from Virtutes apostolorum

- b21 – 34a: Matthew 4:18-20

- b34b – verso a1-12: Matthew 16:13-19

- verso a13 – 32: John 13:3-10

- verso a33 – b10: John 21:15-19

- verso b11 – 38a: Acts 3:1-8

- verso b38b – 39a: Acts 4:22

- verso b39b – 44: Acts 5:14-15

Peter Kidd advised that “Bibles that look like this are not terribly uncommon, but if [it] is a martyrology, it’s much rarer.” I do believe that the manuscript from which this leaf came is a martyrology, based on the contents of the text.

The leaf dates to the 11th or 12th century – likely Italy – but there is something English about it as well.

In the coming months, I plan on spending more time with this binding, and comparing closely the painted L with the initials found in Knut Berg’s Studies in Tuscan twelfth-century illumination (1967), as suggested by Peter Kidd. I’ll also be researching English scribes/foundations in Italy and vice versa and looking more in-depth at birds in medieval manuscripts, as suggested by Michelle Brown.

Any updates will be added to this post, so check back! As always, thoughts and comments welcomed.

n.b. The book is also bound using folio from a ca. 15th century manuscript. The following notes are from the catalog record: “…Two vellum endleaves with an early ms. copy of the Prologue of Book 1, Part 1, of William of Ockham’s Dialogus (text begins: In om[n]ibus curiosus existis …). The front endleaf has a full illuminated border and a large illuminated initial; both endleaves rubricated in red and blue.”

The book: Poliziano, Angelo. Angeli Politiani Miscellaneorum centuriae primae ad Laurentium Medicem praefatio. [Florence : Antonio di Bartolommeo Miscomini, 19 September 1489].

Sources:

“Calendar of Feast Days.” Catholic Tradition.org. Accessed 11 October 2017.

Badke, David. The Medieval Bestiary: Animals in the Middle Ages. 15 January 2011.

Berg, Knut. Studies in Tuscan twelfth-century illumination. Norway: A.S John Grieg, 1967.

Brown, Michelle P. Email messages, 2 – 7 October 2017.

Cappelli, Adriano. The elements of abbreviation in medieval Latin paleography, trans. David Heimann and Richard Kay. Lawrence, Kansas: University of Kansas Libraries, 1982.

Clemens, Raymond, and Graham, Timothy. Introduction to Manuscript Studies. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 2007.

Eastman, David L. The Ancient Martyrdom Accounts of Peter and Paul. Atlanta: SBL Press, 2015.

Ganz, David. “Latin script in England c. 900–1100.” In The Cambridge history of the book in Britain, Gameson, Richard, ed. Volume 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012: 187-224.

Kidd, Peter. Email messages, 4 – 5 October 2017.

Mann, Paul B. Douay-Rheims Bible + Latin Vulgate. DRBO.org. Accessed 2 October 2017.

Migne, J.P. Patrologiae cursus completus: sive biblioteca universalis,integra uniformis… Paris, 1879. Courtesy of Harvard University and Internet Archive.

Rose, Els. “Virtutes apostolorum: Origin, Aim, and Use.” Traditio 68, no. 1 (2013): 57-96.

Steinová, Evina. “Biblical Material in the Latin Apocryphal Acts of the Apostles.” Dissertation, Utrecht University, 2011.

Tillerson, Dianne. Medieval Writing: History, heritage, and data source. 20 February 2016.

Wikipedia contributors. “Ado of Vienne.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Accessed 3 October 2017.

—–. “Crescens.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Accessed 1 November 2017.

Special thanks to Michelle P. Brown and Peter Kidd for their expert opinions.