by Karie Youngdahl, Project Director, History of Vaccines

Robert Abbe (1851-1928), a New York surgeon and Fellow of The College of Physicians of Philadelphia, was an avid collector of medical and archaeological objects. Here at the College’s Historical Medical Library, we hold a number of Abbe’s items, including mementos from his friendship with Marie Curie. Of particular interest to the History of Vaccines project is Abbe’s collection of Louis Pasteur memorabilia, much of it dating from the 1922 centenary celebrations of Pasteur’s birth.

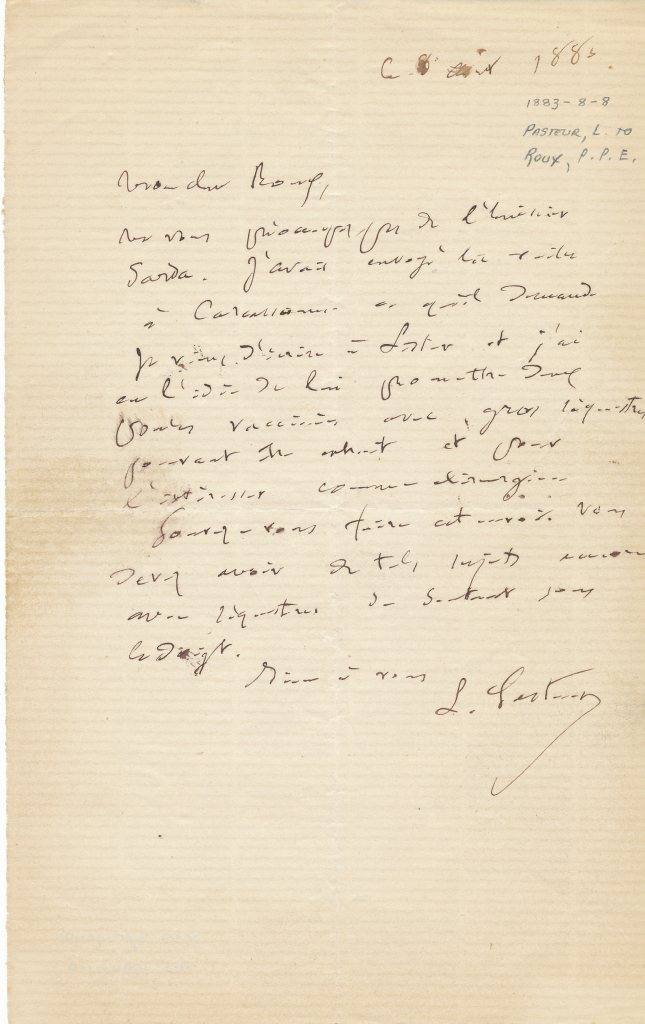

The collection includes a scrapbook with photographs of Pasteur and his family, French postage stamps featuring Pasteur as a national hero, postcards of monuments dedicated to the scientist, and commemorative tags picturing key moments from his life. However, what stands out in the collection is a letter in Pasteur’s handwriting. The letter is intriguing both because it involves several of the 19th century’s most eminent scientific figures and because it presents something of a mystery.

Pasteur addressed the letter to his protégé and collaborator Emile Roux. Abbe included the following translation:

August 8, 1883

My Dear Roux,

Do not bother about that affair of Sarda. I have sent the box for which he asked from Carcassonne. I have just written to Lister and had the idea of promising him two vaccinations of the maximum strength yet made for his use in surgery. Can you send him this—you ought to have something at hand of that strength.

Best wishes, L. Pasteur

Though it’s tempting to speculate about the nature of “that affair of Sarda,” what’s notable about the letter is that it reveals the important connection between Pasteur and Joseph Lister, who is known as the founder of modern surgery. In the 1860s, Lister built on Pasteur’s findings that germs contributed to fermentation and putrefaction: he demonstrated that use of an antiseptic helped prevent wounds from becoming infected. The two struck up a friendly correspondence and met in England when Pasteur addressed the International Medical Congress in 1881 on vaccination for anthrax and chicken cholera.

To which vaccine was Pasteur referring in the letter, and why would Lister the surgeon be interested? In 1883, Pasteur had already had successes with veterinary vaccines for anthrax and chicken cholera. It’s conceivable that he might have been referring to one of those preparations, though one wonders what use Lister would have had with animal vaccines. Pasteur’s first vaccine for use in humans, the rabies vaccine, was still two years away. In the summer of 1883 Pasteur had not yet begun to systematically attenuate the rabies virus, and he would not treat a human with rabies vaccine until 1885.

But what if we take a closer look at the date on the letter and investigate what was happening around the time? The date itself is difficult to read and partially obscured by a smudge. The year could just as easily be 1883, 1885, or 1886. A bit of research reveals that Emile Roux arrived in Alexandria, Egypt, on August 15, 1883, as part of a Pasteur-appointed French commission to investigate a cholera epidemic. Roux would likely have left Paris by the time Pasteur wrote the letter on August 8, 1883.

If the date on the letter was actually August 8, 1885, Pasteur would have already successfully used his rabies vaccine on Joseph Meister, whom he first treated on July 6, 1885. Alternatively, an 1886 date would be contemporary with Lister’s appointment to an English commission charged with investigating Pasteur’s rabies treatment. (In fact, out of Lister’s commission would arise the Lister Institute of Preventive Medicine, for rabies treatment and study of other infectious disease.)

It is instances like this where a small smudge of a date on a letter might make a world of difference in interpreting the sequence of historical events. We hope this is not the last provocative mystery we unearth as we continue to plumb the depths of the collections of the Historical Medical Library. View the finding aid for the Robert Abbe papers here: http://bit.ly/1OT9JRE