– by Robert Hicks, Director of the Mütter Museum & the Historical Medical Library

William Maul Measey Chair for the History of Medicine

By the mid-nineteenth century, Joseph Mellick Leidy (1823-91) was the poster boy of Victorian natural history. A photographic portrait of him in middle age shows a handsome, serious, debonair man, sitting cross-legged, his right elbow casually resting on a table, inches away from a sophisticated brass microscope, its eyepiece tilted towards Leidy. Paleontological specimens line a fireplace mantle behind him. Several disciplines today tag Leidy as their patriarch. He is the Father of American Vertebrate Paleontology. He is the Founder of American Parasitology. His biographer Leonard Warren titled his work The Last Man Who Knew Everything.[1]

Leidy’s An Elementary Treatise on Human Anatomy, first published in 1861, remained a best-seller for medical students for the next half century. According to his inscription in his own book, Leidy partially bound his copy in the collection of the Historical Medical Library with the skin of a Civil War soldier [read more about that here: https://histmed.collegeofphysicians.org/tag/anthropodermics/].[2]

Leidy’s anatomical work inclined toward the artistic and literary. His anatomy drawings are elaborate and colorful in their precision and display Leidy’s fascination with nature. His notes reveal a prose stylist with a flair for the literary. Walt Whitman scholar and poet Lindsay Tuggle (and multiple Francis C. Wood Travel Grantee), in her analysis of Whitman’s Civil War poems, quotes from Leidy’s report of an autopsy on a soldier, whose “Peyer’s glands darkened with inflammation; solitary glands looked like yellow mustard seeds sprinkled on a red ground; large intestines streaked and spotted with ash-color and dark red on a more uniform red ground.” To Tuggle, “Leidy’s florid descriptions of the body’s interior occupy the intersection of anatomy and botany…”[3] At any scientific moment, Leidy reached beyond disciplinary boundaries to meditate on the meaning of his work. No surprise, then, that he was curious about Philadelphia’s literary scene.

By 1887, Leidy served as professor of anatomy at the University of Pennsylvania, where he also headed the biology department, which he had founded two years earlier. He also found time to reign as president of the Wagner Free Institute of Science and as curator of the Academy of Natural Sciences. Widely known in Philadelphia, he maintained membership in dozens of professional societies including the American Philosophical Society and The College of Physicians of Philadelphia. On Washington’s birthday that year, February 22, Leidy entered a carriage on a clear, cold night shortly after 7pm and headed to a talk scheduled at the Guild of Working Women (later the New Century Guild and now the New Century Trust), a support organization that offered its premises for that night’s meeting of the Contemporary Club. Walt Whitman was the speaker.

Organized only the previous year, the Contemporary Club functioned until the 1950s as a social and literary gathering where members could hear, discuss, and debate papers on current events and the arts. Lectures began at 8:30 and according to club rules could not exceed 50 minutes. Presentations were followed by two ten-minute presentations by members chosen as discussants or debaters. Physicians and colleagues S. Weir Mitchell, W.W. Keen, and Horatio C. Wood were longtime members (and all were Fellows of The College of Physicians of Philadelphia). The club’s treasurer, and one of the founders, essayist, publisher, and Whitman acolyte, Horace Traubel, probably arranged for Whitman’s appearance. Partially disabled by a stroke in 1885 which prevented him from climbing stairs, 67-year-old Whitman nevertheless agreed to appear that night.

Two weeks before the speech, Traubel had encouraged Whitman to compose some brief comments, but somehow the poet never got around to it. On February 22, Traubel summoned a carriage to convey them both to the meeting. The carriage took them to the Delaware River ferry to Philadelphia, and during the ride Whitman chatted with the ferry deckhands. The cold air invigorated the poet, who said, “’It is like a new grant of health and freedom.’”[4] At the meeting venue on Girard Street near the corner of 11th Street, drivers of parked cabs helped Whitman up the stairs into a small, cramped room. Traubel took Whitman’s coat and hat, and the poet sat down “among the irregular clusters of members and their friends.”

Traubel ushered Whitman to a small platform as the poet asked to ventilate the room. Traubel describes the moment:

The scene was unique and impressive. The contrast of his simple, massive exterior—his voice, élan, smile–with the literary, intellectual, often social pomp of the group about him, was great. Some of us sat along the edge of the platform at his feet, others stood behind him. He was practically surrounded. But whatever the contrast, the doubt, the critical feeling, his own bearing shamed all antagonistic assertion. His freedom and spontaneity were, in fact, almost exasperating. He would not for instance, talk of poetry, of philosophy, of art, or of anything which would inaugurate controversy. Subtle inquiries were advanced and passed.

Whitman read three poems, beginning with “The Mystic Trumpeter,” which includes the lines:

Blow trumpeter free and clear, I follow thee,

While at thy liquid prelude, glad, serene,

The fretting world, the streets, the noisy hours of day withdraw,

A holy calm descends like dew upon me,

I walk in cool refreshing night the walks of Paradise,

I scent the grass, the moist air and the roses;

Thy song expands my numb’d imbonded spirit, thou freest,

launchest me,

Floating and basking upon heaven’s lake.[5]

Whitman followed with “A Voice from the Sea” and “Midnight Visitor.” The latter poem was an odd inclusion. Whitman read his own revision of an English translation of a poem by French poet and novelist Henri Murger (1822-61).[6] The sentimental poem contrasted with Whitman’s, but according to Traubel the audience enjoyed the reading nonetheless.

At the conclusion of the reading, says Traubel:

Whitman answered one or two of the more innocent questions that were put. One response, dealing with the idea of procedure and system; “Method does not trouble me, my own method or that of others, provided I or they ‘get there”—excited much amusement. His reading was solemn and impressive. There was some further program, in which he apparently took little interest. He chose his own time to whisper to me his desire to go. On the way down-stairs he took a sip or more of tea or coffee. He was led out as he had been led in. On the step he turned to me—I had one arm—and made some remark about the glory of the stars and how good it was to be free with them again. The drivers here all circled him again, offering congratulations and help.[7]

We do not know if this was the only instance of Leidy’s attending a Whitman poetry reading. Whitman returned to the Contemporary Club one more time, in 1890, to deliver a popular memorial on Abraham Lincoln, a talk at which S. Weir Mitchell participated as discussant, but there is no evidence that Leidy attended. Although courted by the club, Leidy evidently did not sustain his interest. The Historical Society of Pennsylvania holds the archive of the Contemporary Club, and although Leidy’s name does not appear on any surviving membership list (and they are spotty in dates), a note (dated October 27, but no year given) to the club secretary mentions that “Professor Leidy” should be dropped from the membership list, a “matter [that] was decided” at a previous [membership] committee meeting.[8]

Did Leidy form an acquaintance with Whitman? Apparently not, although fellow physicians S. Weir Mitchell, his physician son John, and William Osler regularly dropped in on Walt at his Camden home to conduct medical consultations. The elder Mitchell paid for a nurse to be in attendance during Whitman’s final two years.[9] How might Leidy have responded to Whitman? The two men were alike in their rejection of dogma, lack of ambition for honors and accolades, and indifference to institutional hierarchies. Both developed a holistic view of their place in the world and in nature. Where Leidy took to the microscope and the dissection microtome to find anatomical linkages between people and the natural world over geologic time, Whitman contained comparable multitudes in his expansive words about the American character and destiny. One friend identified Leidy’s favorite writers as Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr. One of the latter’s poems “had an especial charm for him,”[10] “The Chambered Nautilus,” which included words that freed another “numb’d imbonded spirit”:

Build thee more stately mansions, O my soul,

As the swift seasons roll!

Leave thy low-vaulted past!

Let each new temple, nobler than the last,

Shut thee from heaven with a dome more vast,

Till thou at length art free,

Leaving thine outgrown shell by life’s unresting sea![11]

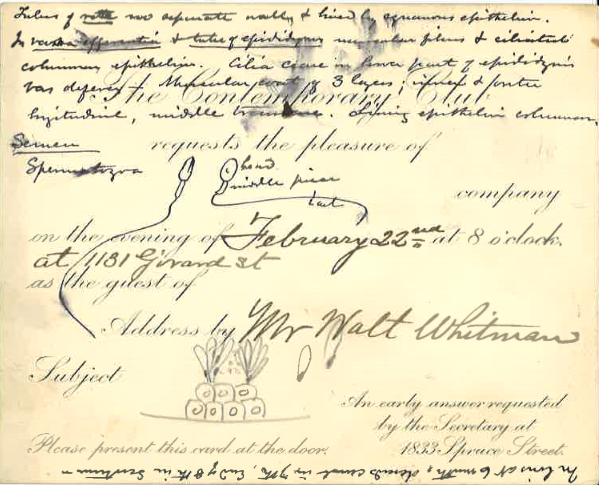

A number of Leidy’s professional papers and drawings reside in the archive of The College of Physicians of Philadelphia. The oddest item in the lot is Leidy’s invitation to the 1887 lecture by Whitman. The printed card left spaces for the date and speaker, and Whitman’s autograph appears opposite “Address by.” Leidy was an inveterate scribbler of notes on whatever scraps were at hand, and he evidently withdrew the invitation from his pocket at some later time and prepared lecture notes on the anatomy of the human scrotum. He drew pictures of two spermatozoa that have gravitated to the words “requests the pleasure of.” Every unfilled space contains an ordered sequence of notes about the “Testes or Testicles,” with the names of all key structures underlined. The notes appear to have served for an anatomy lecture, not a publication, since Leidy never published on the topic after 1887. Perhaps this card served as Leidy’s aide memoire as he stood before students at the University of Pennsylvania.[12] Tuggle finds this re-purposed invitation “a pithy twist of intimate humor that would no doubt have delighted Whitman.”[13] The poet and the scientist might have been closer intellectual sparring partners than either might have suspected.

Endnotes:

[1] A biographical sketch about Leidy can be read here: <https://archives.upenn.edu/exhibits/penn-people/biography/joseph-mellick-leidy>, accessed April 25, 2019.

[2] The inscription in Leidy’s own hand on the insider cover reads, “The leather with which this book is bound is human skin, from a soldier who died during the great Southern Rebellion.”

[3] Lindsay Tuggle. The Afterlives of Specimens: Science, Mourning, and Whitman’s Civil War (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2017), 87.

[4] From Horace L. Traubel, In RE Walt Whitman (Philadelphia: David McKay, 1893): 130-1, The Walt Whitman Archive <https://whitmanarchive.org/criticism/interviews/transcriptions/med.00581.html>, accessed April 25, 2019.

[5] “The Mystic Trumpeter,” The Walt Whitman Archive, <https://whitmanarchive.org/published/LG/1891/poems/268>, accessed April 25, 2019.

[6] See Arthur Golden, “The Text of a Whitman Lincoln Lecture Reading: Anacreon’s ‘The Midnight Visitor,” Walt Whitman Quarterly Review, 6.2 (1988): 91-94.

[7] Traubel, In RE Walt Whitman.

[8] Note to Secretary Mrs. Talbott Williams, Incoming Correspondence, Box 4, Folder 1, Contemporary Club (Philadelphia, Pa.) records, Collection 1981, Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

[9] Nancy Cervetti. S. Weir Mitchell, 1829-1914: Philadelphia’s Literary Physician (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2012), 171.

[10] Henry Fairfield Osborn, “Biographical Memoir of Joseph Leidy 1823-1891,” p. 350. Online at <http://www.nasonline.org/publications/biographical-memoirs/memoir-pdfs/leidy-joseph.pdf>, accessed April 26, 2019.

[11] The entire poem can be read at the Poetry Foundation website: <https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44379/the-chambered-nautilus>, accessed April 26, 2019.

[12] Joseph Leidy, Notes to his course on anatomy at the University of Pennsylvania, n.d., “Urogenital System,” envelope #12. Historical Medical Library, The College of Physicians of Philadelphia.

[13] Tuggle, 88.