– by Marie Hathaway, Library Assistant

Prior to the closing of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia for COVID-19, my co-worker Kristen Pinkerton and I were working in the stacks at the Historical Medical Library processing journal volumes for deaccessioning and updating metadata for journals that will remain. Going through the collection volume by volume to update metadata allowed us to get to know the collection in ways we might not have based on researcher requests alone. We were continually surprised. Just in the week prior to closing I found a colorful pamphlet about WWII-era chemical warfare and Kristen found a year book featuring a medical student’s romantic poem about spermatozoa.

As we’ve transitioned from working in the stacks to working from home, Kristen and I have been helping to comb through another part of the library’s collection—its digital resources. Like the physical stacks, the online collection has proven to be full of surprising and fascinating information.

Our first project has been transcribing a set of digitized questionnaires given to veterans who lost limbs in and around the Civil War. These questionnaires are part of the library’s Silas Weir Mitchell Papers collection. Mitchell, who served as a surgeon at Turner’s Lane Hospital in Philadelphia during the Civil War, specialized in the study of nerve damage. These questionnaires, conducted in 1893 by his son Dr. John K. Mitchell and Dr. Edward Martin, were an essential part of continued research on the long-term effects of amputation.

As Mitchell and Martin explain in a letter contained in the collection, they obtained approval of the Surgeon General and assistance from the War Department in conducting the study of wounded veterans, some twenty years after the war. The intention was for the forms to be filled out with the assistance of the respondent’s family physician. This was probably to limit misunderstanding of medical terms such as suppuration (the production of pus—these questionnaires are not for the squeamish), to aid in instances where the veteran had lost the use of his hands, and also perhaps to increase the likelihood of full responses. However this was not always possible. Several men indicated that they were unable to afford a doctor’s fee, and so had filled it out on their own.

Something we were struck by almost immediately is that this questionnaire is not always effective at getting meaningful responses from the veterans. There is confusion from the beginning, when the form asks for the date of amputation right before asking the nature of the wound. This led some respondents to describe their operation rather than their initial injury.

The vague wording of questions such as, “How extensive is the area of altered sensation?” followed shortly by, “How far does the altered sensation extend?” elicit confused and frustrated responses. The men often seem to feel that they have already answered sufficiently and so respond “as above” or just leave it blank.

Rather than getting these veterans to open up about their experiences, the rapid fire questions have a way of shutting them down. They don’t often elaborate, or they weren’t given the proper space or prompting to respond effectively. Responses get more antagonistic as questions stack up. You can almost hear them exasperated, wanting to get it over, “No. No. No. No. ——” At times respondents sound almost sarcastic, especially when speaking about their operations. One man described his post-amputation symptoms as, “Nothing special except severe pain.”

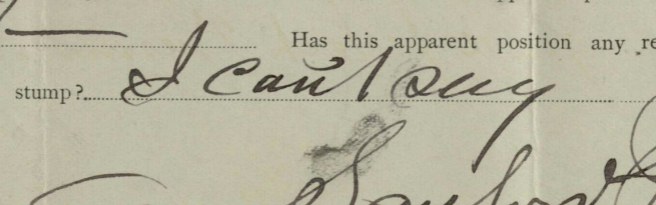

The last question is perhaps the most confusing of all, “Has this apparent position any relation to the position of the stump?” Sanford Pettibone responds, “I can’t say.” He may well have meant it with a simple shrug, but I felt the weight of these words. The frustration at the inability to convey this painful, life-altering experience even when asked to, perhaps because the asking was not the most skillful.

But to be fair, we see this questionnaire through the lens of our contemporary world where doctor-patient communication and survey methodology are growing fields of study. And the fact that Mitchell and Martin did ask, that they were interested in these men—in how they were wounded, treated, and coping; in the strange, lingering effects of their injuries—was unprecedented at the time and yielded some compelling results.

The wounds sustained by the respondents offer a window into the dangers specific to the Civil War and other conflicts of the era. Railroad accidents, frostbite, gangrene, gunshot wounds, and premature cannon fire are among the culprits. We also see several specific mentions of a new technology at the time, the Minié ball. This vicious little innovation of warfare may have increased the need for amputation. Its speed meant that rather than lodging somewhere in the flesh, as round balls tended to do, a Minnie ball would zip clean through. Unless it hit bone that is, in which case the bone would often shatter.

The questionnaire also asks the veterans what type of “artificial appliances” (prosthetic limbs) “has been most satisfactory.” Several with leg injuries used prosthetics developed by Dr. Douglas Bly, who pioneered the invention. However the many respondents were not so satisfied. E.D. Watkins had a prosthetic fitted by Bly, but “could not use it.” Charls Ritchey said it “made the leg sore + exposed bone.” Lewis A. Horton found Bly’s device to be “tiresome, of no use.”

It’s a small data set, but striking patterns emerge. Even respondents who report almost no changes to their overall health mostly respond affirmatively to the question about whether their stumps are sensitive to certain winds. Several indicate that their injury, or perhaps the shock from the operation itself, impacted their hearing. And every respondent reports some degree of what we now refer to as phantom limb syndrome, though they all describe it differently. Wesley James says, “I feel the hand but it feels like the fingers grew out at the wrist.”

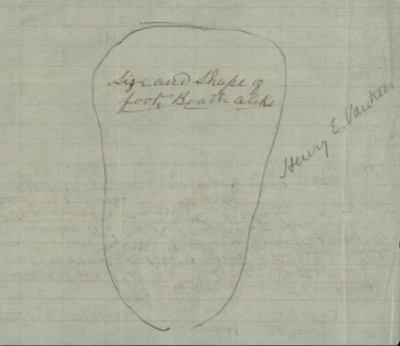

The questionnaire asks respondents to “Give length and shape of stump.” Which not many seem inclined to answer. However Henry E. Van Trees actually took the time to draw, or perhaps trace, the stump of his foot.

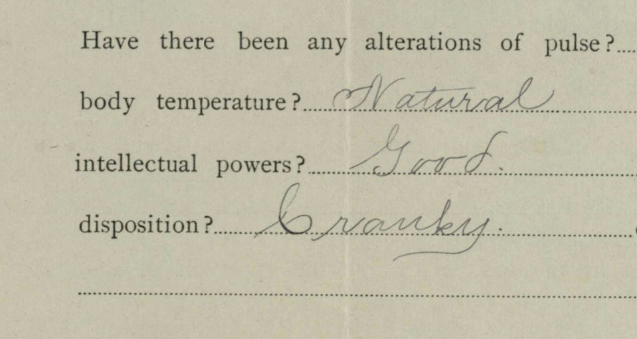

Transcribing the words of these men sparked our curiosity and inspired us to do a little extra digging. Kristen transcribed the very complete questionnaire and letter of Henry A. Kircher, which prompted her to research him, and she found that he wrote a book. She also discovered that Lewis A. Horton was one of the first noncombatants to receive a National Medal of Honor. Another Medal of Honor recipient among respondents, Richard D. Dunphy, indicated that his operation (the amputation of both of his arms) took place aboard the USS Hartford. I was amazed when a quick search for this ship revealed a picture of Dunphy himself and clarified that his wounds occurred during the Battle of Mobile Bay. One of Dunphy’s responses remains my favorite of the collection. When asked whether or how his amputation had altered his disposition, he answered simply, “Cranky.”

For all the limits of Mitchell and Martin’s questionnaires, for all the unanswered questions and terse or confused answers, they are filled with voices—some sorely wounded and bitterly shattered; some stubbornly unflappable and humorously defiant. We’ve enjoyed getting to know them, and we hope you will too.