– by Charlie Dawson, Visitor Services/Gallery Associate

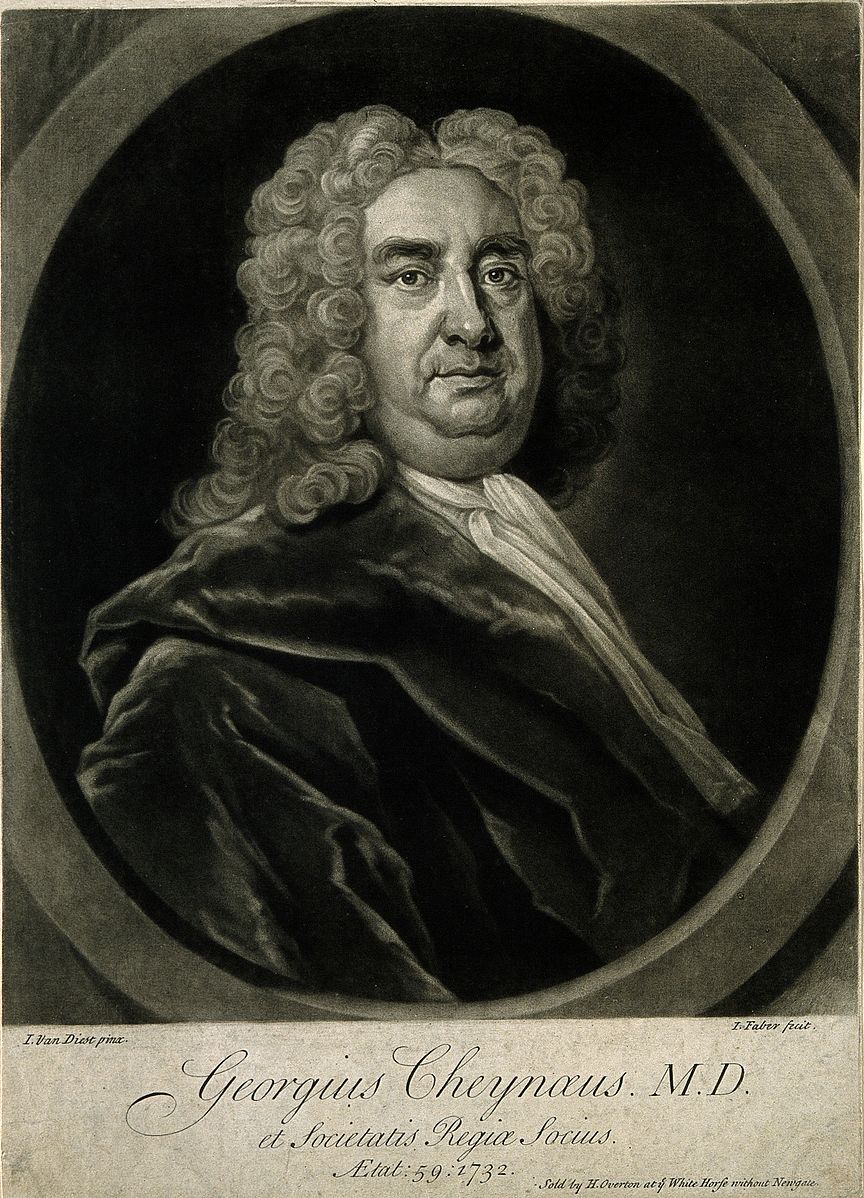

George Cheyne was a Scottish physician best remembered as an early advocate of vegetarianism. Born in 1672, he moved to London as a young man and became a regular in the local taverns. After ballooning in weight, he adopted the extremely restrictive diet for which he is best remembered today.

Cheyne – a corpulent physician who chided his patients to eat less – became a target of satire for his hypocritical sermonizing: Yet he was a strong believer in his own advice, writing in one book:

“Some perhaps, may controvert, nay ridicule, the Doctrin laid down in these positions. I shall neither reply to, nor be moved with, any thing that shall be said against them.”

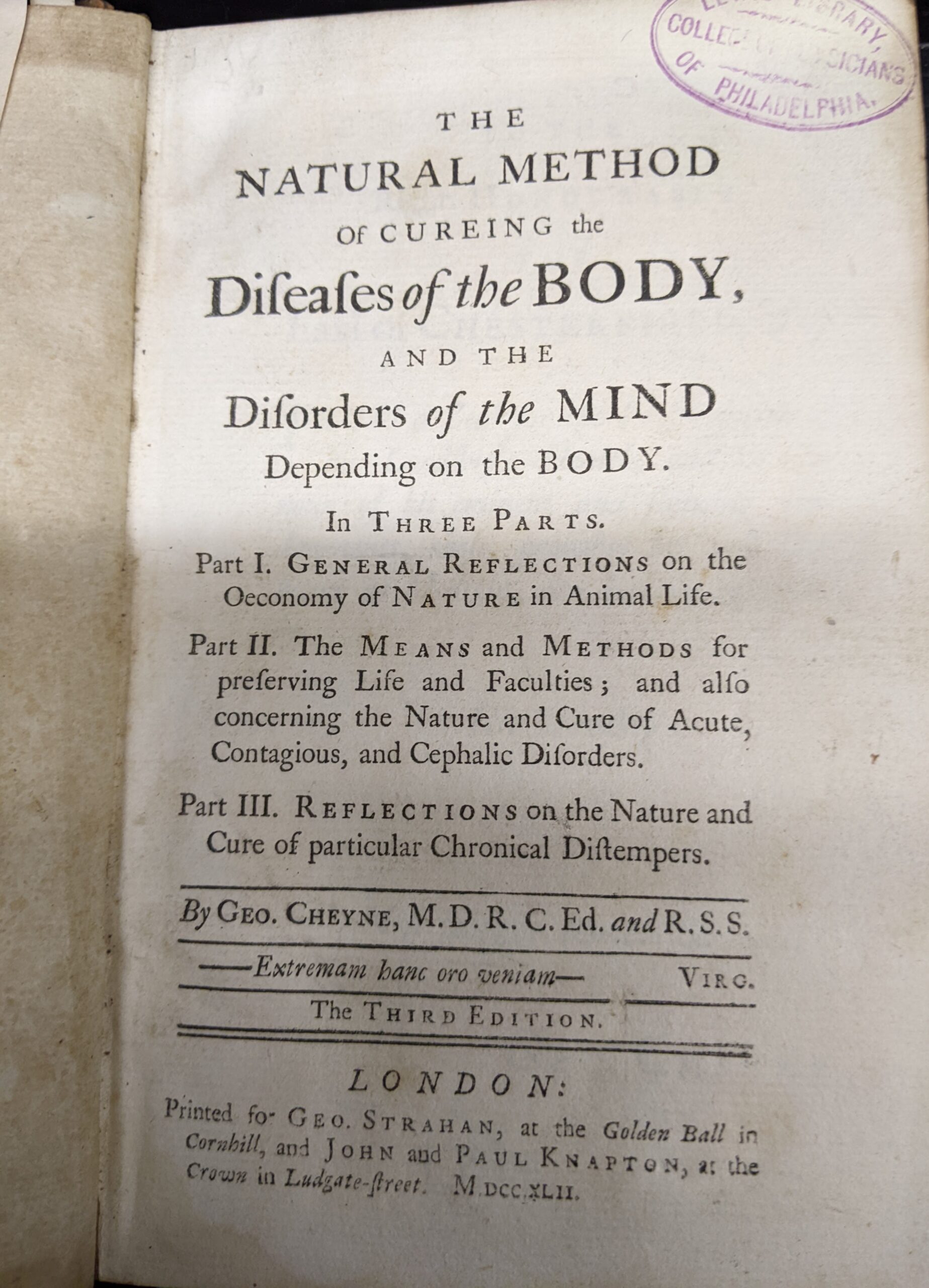

This article considers two books by George Cheyne in possession of the Library of the College of Physicians. In The English Malady (1733), Cheyne looks at nervous disorders as a trait predominating among the English. In The Natural Method of Cureing Diseases of the Body and the Disorders of the Mind (1742), he sums up his philosophy of illness as arising primarily from poor diet.

Even in the early eighteenth century, Cheyne was beholden to the wisdom of the ancients. He begins The Natural Method with a reference to the long lives of the Old Testament patriarchs, saying that people live longer when times are tougher because their diets are plainer and they exercise more. He notes that alcohol was unknown before Noah’s flood, and that it led to drunkenness and incest afterward.

This was only the dawn of the “micromechanical evolution,” as physicians became increasingly aware of the finer details of human anatomy. Although his books display awareness of the body’s interior structure, Cheyne concentrated on practical, lifestyle advice centered on diet. His writing is silent on communicable diseases like plagues and smallpox.

Cheyne envisioned the body as a system of pipes requiring an even, easy flow of liquid. (The body’s solids come from the father, he tells us, and its juices from the mother.) He’s primarily concerned that the blood be “fluid, sweet, and balsamic.” He condemns animal fats, by contrast, as tending to make the blood “hot, viscid, and glewy.”

Although an early vegetarian, Cheyne’s recommended diet is heavy on milk. For the ailing, he prescribes a total milk and seed diet, particularly for people past middle age and those in sedentary occupations.

Cheyne touts the importance of exercise, although the examples he gives are not exactly cardio intensive: “Hunting, Shooting, Bowls, Billiards, Shuttle-cock.” He also recommends inducing vomiting for the exercise it gives via the spasming and convulsing of the digestive system.

When Cheyne does touch on medical intervention, his answer is almost invariably mercury: for rabies (called Hydrophobia), for cancer, for gout. He believed mercury particles to be perfectly spherical, and so ideal for flushing out obstructions in the veins.

Natural Methods touches only briefly on issues particular to women. He rails against constant bed rest during pregnancy, writing, “It is a vulgar Error to confine tender breeding Women to their Chambers, Couches, or Beds.” He approves of breast milk, or at least he would if the majority of nursemaids weren’t so unclean and lowborn.

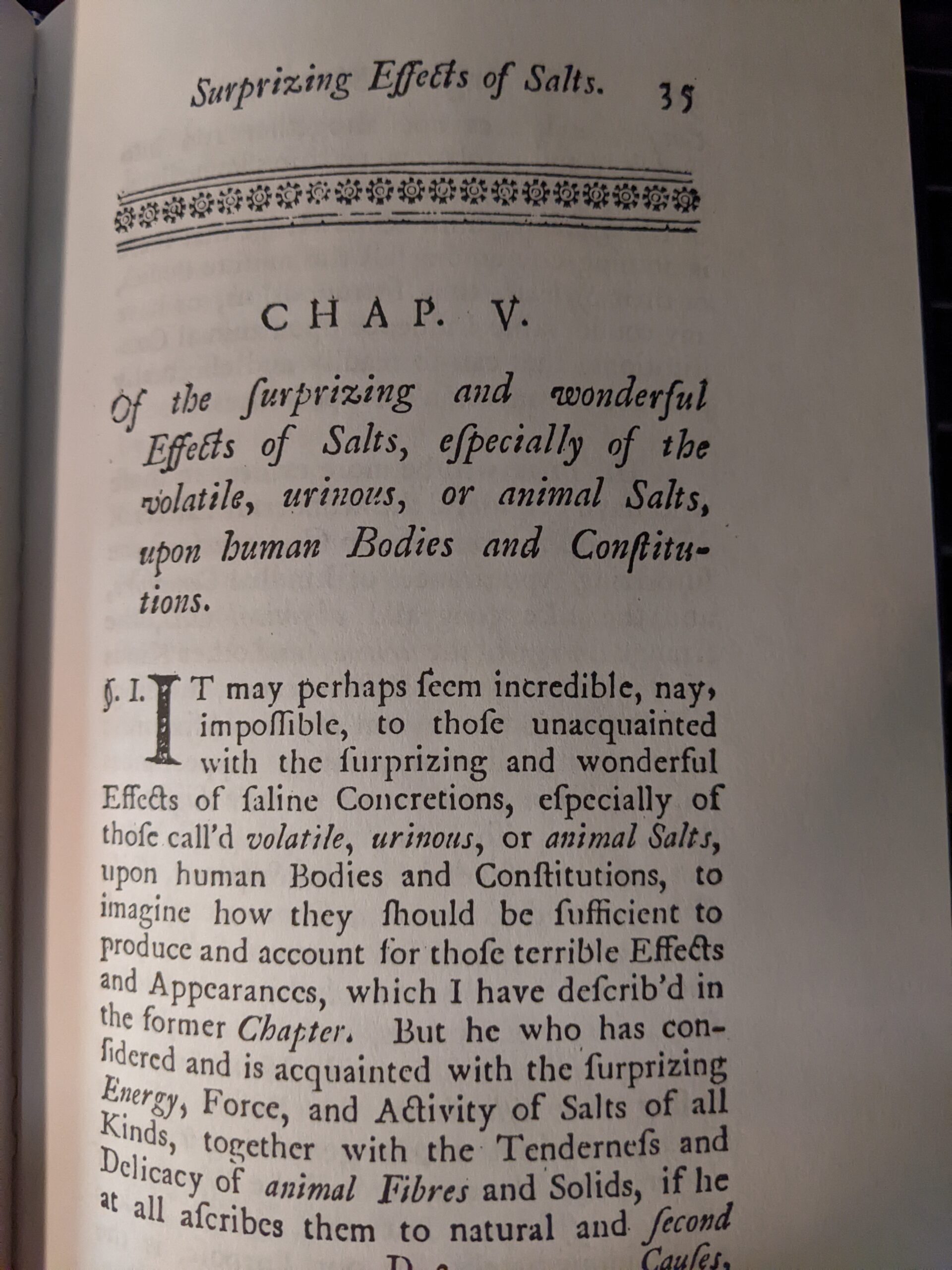

The English Malady takes its title from a phrase, apparently in use in Europe, to describe melancholy, lethargy, and a range of symptoms described as nervous disorders. At their mildest, nervous disorders include yawning and symptoms. At their most severe, they include epilepsy and mania.

A chapter in The English Malady (left) and the title page for Natural Methods (right).

Cheyne believed, as others did, that nervous disorders were particularly common among the English, and he blames:

“The Moisture of our Air, the Variableness of our Weather,…the Richness and Heaviness of our Food, the Wealth and Abundance of the Inhabitants, (from their universal Trade) the Inactivity and sedentary Occupations of the better Sort (among whom this Evil mostly rages) and the Humour of living in great, populous, and consequently unhealthy Towns.”

He also details “Spleen” or “Vapours,” which most encompass modern ideas of mental illness. This extends to:

“All Lowness of Spirits… Noise in the Bowels or Ears, frequent Yawning, Inappentency, Restlessness, Inquietude, Fidgeting, Anxiety, Peevishness, Discontent, Melancholy, Grief, Vexation, Ill Humor, Inconstancy, [and] lethargick or watchful Disorders.”

For the sufferer, there is at least the consolation of good company. Cheyne tells us that nervous disorders are almost unknown among “Fools, weak, or stupid persons, heavy and dull Souls.” In addition, although people of fair hair color have weaker nerves, they are quick thinkers, and most readily feel both pleasure and pain.

Though Cheyne offers a number of factors contributing to nervous disorders, he is most concerned with a diet consisting of “the Too-high or Too-much.” Vegetables, by contrast, avoid “unnatural Cramming.” God made us for a purpose, Cheyne tells us, but disease arises from abuse of this freedom as well as “spurious Self-love.”

It can be a blessing, then, to have weak nerves and thus be saved from the temptation to overindulge available to the robust and healthy. One is reminded here of Cheyne’s estimation of his own constitution:

“As for myself, I have been all my Life of a Spongy, flabby, relax’d Habit, of weak Nerves originally, easily ruffled, surprised and hurried.”

If concern for one’s body is not enough to take diet seriously, Cheyne points to the “obtuse intellectual organs of those who consume recklessly,” which end in that most unfortunate figure, the “Mediocria Ingenia.”

For those like himself, who approach middle age regretting a youth of overindulgence, Cheyne recommends periodic fasting, though never, thankfully, for more than three or four days. He points to his colleague Isaac Newton, who made his greatest breakthroughs while confining himself to only bread and water. Cheyne instructs us to treat our body like a domestic animal: with a disciplined diet and a focus on cleanliness and exercise.

Cheyne is not above resorting to purges – of blood and other substances. But he insists on the primacy of diet, averring that his total milk and seed diet:

“Would sooner, more pleasantly, and more durably, cure and extirpate all kinds of Mania, Phrensies, and Madness, (which are so shamefully frequent in Britain) than the common one of treating them with tearing Emetics, and scraping Cathartics.”

After focusing for so long on the body’s delicate pipes and fibers, Cheyne closes The English Malady by zooming out to leave us with some perennial good advice, writing:

“Nothing will more contribute towards the Felicity of Green Old Age, than innocent and entertaining Amusements, engaging and light Studies, and rational Diversions in a chearful and affectionat Society.”

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Shapin, Steven. Trusting George Cheyne: Scientific Expertise, Common Sense, and Moral Authority in Early Eighteenth-Century Dietetic Medicine. Bulletin of the History of Medicine 77:2. 2003

Cheyne, George. The Natural Method of Cureing the Diseases of the Body and the Disorders of the Mind, Depending on the Body. George Strahan and John and Paul Knapton, 1742.

Cheyne, George. The English Malady: Or a Treatise of nervous diseases of all kinds; as spleen, vapours, lowness of spirits, hypochondriacal, and hysterical distempers, etc. S. Powell, 1734.