– by Patrick Magee, Visitor Services/Gallery Associate

Welcome to #MedievalMedicineMonday! On Mondays, Patrick Magee, Visitor Services/Gallery Associate, will be exploring the depths of medieval botanical medicine as depicted by woodcuts found in our early printed books.

Although commonly held beliefs over medicine change quite a bit over time, one thing that’s certain is the ceaseless documentation of every turn of events within the medical world, from plague to poison. Medicinal science involves a lot of trial and error, and sometimes what seems like an inscrutable idea at first can become the backbone of treatment. In this series of posts on medically significant plants, we wanted to beg several questions – which plants do we still use? Which ended up being effectively snake oil? What was for health, and what was for fun? All of these questions and more will be addressed over time, starting in this case with a fungus.

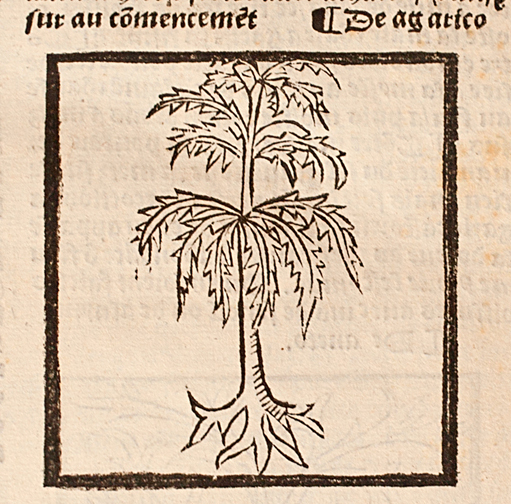

Pictured above from the Historical Medical Library of The College of Physicians of Philadelphia (Library) is a woodcut of “De Agarico (Laricifomes officinalis)” or the agaric, a wood-grown fungus known for its bitter taste and decay-inducing properties on hosts. Beyond its basic characteristics, however, Agarico was also notable because of its unique ability to treat sweat related symptoms associated with tuberculosis (at the time of this illustration known as “consumption”).

Agaric was typically distributed in the form of a lozenge, itself made by combining ginger, a gum and the agaric fungus. Although the woodcut illustration provided in the Library collection depicts the fungus alongside a midsized plant, it can actually be found in many forms and colors, as the “agaric” term itself is intended for a broader use than, say, “Amanita muscaria.” Like most mushrooms, it’s typically found at the base of trees, although there are always exceptions when it comes to fungus.

The particular woodcut illustration of the agaric fungus present in the Library collection is from approximately the late 1400s-early 1500s, and other historical record indicates that the fungus was being used for medical purposes by as early as the 1700s (“Agarico. Trociscato”). Tuberculosis had done quite some damage on the world prior to the periods of breakthroughs powered by modern medicine, and it was not until the late 1800s that the disease was even identified as contagious. Prior to the discovery of potential treatments, many patients with the disease would either waste away or face a lifetime of difficult relapses.

Agaric fungus was medically useful in the tuberculosis outbreak because “the Agaricus polysaccharide fraction (ingredient inside the mushroom) [had] significant immune activation power” (“Agaricus / Agaricus Muscarius / Amanita Muscaria / Fly Agaric”). It was believed that exposure to several doses of agaric over the course of time would help aide the immune system with the difficult work of taking on TB. Tuberculosis was often treated with lozenges derived from agaric fungus, as exhibited in the Smithsonian National Museum of American History by this container specifically for agaric (“Agarico. Trociscato”).

The number of yearly tuberculosis cases and deaths has gone down considerably over time with between the older innovations of solutions like agaric, improved testing, awareness campaigns, and all of the other great hallmarks that come with great pandemic management. As of 2015, the rate of tuberculosis cases per an average population of 100,000 people dipped below five percent overall (“Surveillance Slides | 2015 | Surveillance Report | Data & Statistics | TB| CDC”).

It turns out that modern medicine had a place for agaric fungus as well. The agaric fungus varieties classified as non-poisonous over time are now known to “[…] strengthen the immune system, fight tumor development, and work as an antioxidant,” particularly in people with cancer (https://www.webmd.com/vitamins/ai/ingredientmono-1165/agaricus-mushroom). Although this is obviously a different set of ailments and conditions, this does highlight the legitimacy and validity of agaric as a form of medical treatment over time.

There is always a slight ebb and flow to trends in world health – as time passes, medical circumstances change, public knowledge adjusts and takes in new information, new habits are adapted and eventually entire standards of living are created around both the diseases we can easily fight off (with vaccines) and the ones we have much to learn about still (those of a yet-to-be-cured and/or chronic nature). What we can learn from this is that what starts off as unusual – in this case, attempting to find medical value in a type of natural life that’s been known to come in poisonous forms – can end up proving extremely medically substantial.

Sources:

“Agarico. Trociscato.” National Museum of American History, americanhistory.si.edu/collections/search/object/nmah_993475. Accessed 18 Dec. 2020.

“Agaricus / Agaricus Muscarius / Amanita Muscaria / Fly Agaric.” Www.Herbalremedies.com, www.herbalremedies.com/agaricus-information.html. Accessed 18 Dec. 2020.

“Agaricus Mushroom: Uses, Side Effects, Interactions, Dosage, and Warning.” Www.Webmd.com, wwww.webmd.com/vitamins/ai/ingredientmono-1165/agaricus-mushroom. Accessed 18 Dec. 2020.

“Surveillance Slides | 2015 | Surveillance Report | Data & Statistics | TB| CDC.” Www.Cdc.Gov, 12 Dec. 2018, www.cdc.gov/tb/statistics/surv/surv2015/default.htm. Accessed 18 Dec. 2020.