On September 7, 1918, 300 sailors arrived in Philadelphia from Boston, where, two weeks earlier, soldiers and sailors began to be hospitalized with a disease characterized as pneumonia, meningitis, or influenza. The sailors were stationed at the Philadelphia Naval Yard.

On September 11, 19 sailors reported to sickbay with symptoms of “influenza.” By September 15, more than 600 servicemen required hospitalization.

Physicians and other public health workers in Philadelphia first met on September 18 with city officials to discuss what they perceived as a growing threat. Public health officials demanded that the city be quarantined – all public spaces, including schools, churches, parks, any place people could congregate, should be closed. City officials did not want to create panic. They were more concerned that local support for President Wilson’s efforts in World War I should not be disturbed. Anything that would damage morale – or the city’s ability to raise the millions in Liberty Loans required by federal quota – was unacceptable.

The Board of Health declared influenza a reportable disease on September 21, which required physicians to report any cases they treated to health officials. The Board advised residents to stay warm and keep their feet dry and their bowels open. The Board also suggested that people avoid crowds.

Against the calls for quarantine, the city hosted a Liberty Loan parade on September 28. The two-mile route south on Broad Street was complete with marching bands, Boy Scouts, women’s auxiliary groups, soldiers, sailors, flags, and patriotic fervor. It is estimated that more 200,000 people attended the parade.

Within 72 hours of the parade, every bed in Philadelphia’s 31 hospitals was full.

We are saturated with information today. We not only consume it, but we create it through social media posts, YouTube videos, blogs, and so on. A May 2018 article in Forbes magazine notes a terrifying thought (at least for a librarian): “Over the last two years alone 90 percent of the data in the world was generated.” Few public events today escape immediate documentation.

Researchers who are examining the 1918 influenza pandemic expect to find rich sets of primary sources at the Historical Medical Library. Unfortunately, their expectations are met with disappointment.

A simple search on the term “influenza” in the Library’s OPAC (online public access catalog) shows 688 hits across both Library and Mütter Museum collections regardless of publication or creation date. Library collections, while greater in number, are mostly secondary sources, with only a small number (19) published in the years between 1918 and 1925.

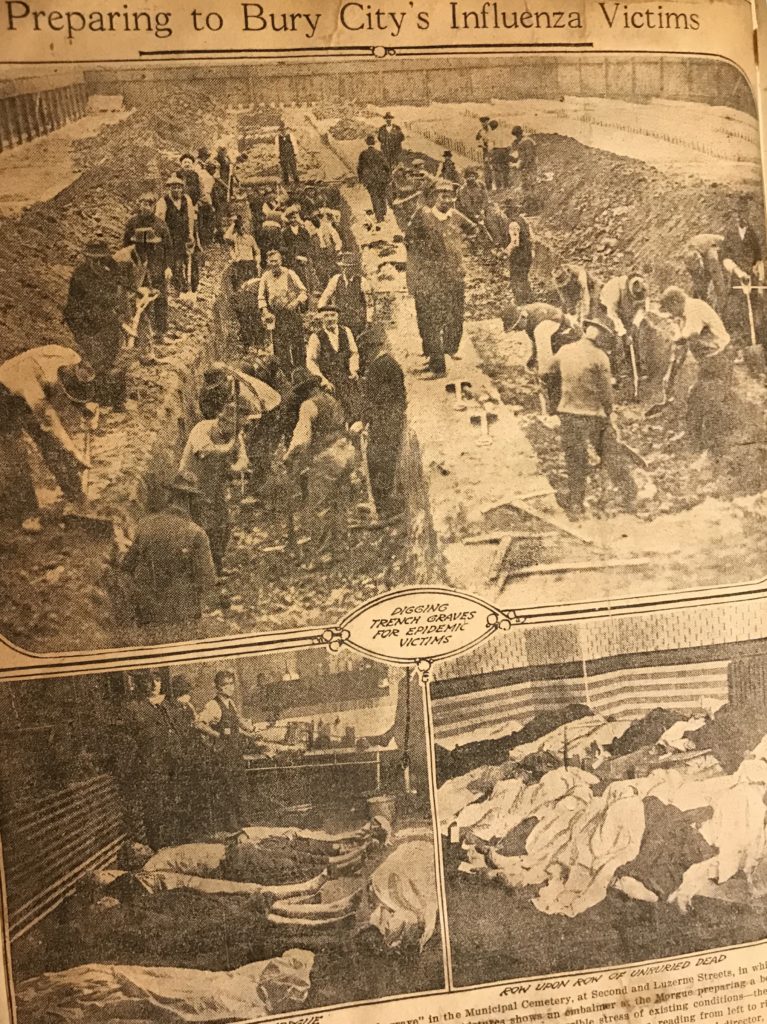

The most significant primary source in the collection of the Historical Medical Library is a scrapbook of newspaper clippings contemporary to the pandemic in Philadelphia. The majority of the clippings are not dated. A small number have enough of the masthead visible to safely assume that some, if not all, of the clippings were taken from the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin. The clippings are pasted edge to edge, roughly clipped, and assumed to be in date order. There is no provenance available to determine who created the scrapbook – it was acquired by the Library on October 19, 1919, through the Medical Library Association’s Exchange program, which encouraged medical libraries throughout the United States to swap items outside of their own collecting scope.

Why, then, are there so few extant primary sources about the influenza pandemic in the collections of The College of Physicians of Philadelphia?

The Historical Medical Library was founded in 1788, one year after the founding of The College of Physicians, which is the oldest medical fellowship in the United States. The Library was developed mostly through donations of books, manuscripts, and archival collections, but also through small acquisition funds and, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the aforementioned Exchange program. The collection reflects the interests of the Fellows of the College at any particular time in the history of the College. The evolution of medical specialization is particularly evident in the subject of books acquired; the development of the manuscript collections reflects the interests and work of those Fellows most closely affiliated with the College.

The College offered Fellows the opportunity to publish works in the Transactions & Studies of The College of Physicians of Philadelphia, which was issued between 1793 and 2002. Again, the Transactions reflect contemporary medical practice and concerns, as well as the research and teaching of Fellows.

The College was prominent in public health in Philadelphia since its founding. In November 1787, a month after the founding of the College, Benjamin Rush composed what was called a “memorial” to the Pennsylvania State Assembly promoting temperance as a measure of public health. In 1848, the College acted to mitigate urban overcrowding, intemperance, tainted food and water, poor sanitary conditions, and the solitary confinement of prisoners in city jails. After the Civil War, the College addressed issues related to industrialization, street cleaning, and the creation of public sewers and indoor plumbing. In 1883, a report was submitted to the state legislature stating “Philadelphia is now recognized as the worst-paved and worst-cleaned city in the civilized world.”

In 1912, the College created the Committee on Public Health and Preventive Medicine, one of a number of official committees that had promoted public health issues over the years. This Committee addressed long working hours for women and children, the use of night soil as a fertilizer, keeping hogs within the city borders, compulsory vaccination against smallpox – and clean streets.

One would assume that an institution committed to an active public health role within one of the country’s largest cities would have a prominent response to the 1918 influenza pandemic. Instead, between 1917 and 1925 the words flu, influenza and epidemic appear only infrequently in any College records and College publications. (Transactions published in fall 1918 and early 1919 mention a symposium that occurred at the College on complications of influenza in the “current epidemic” and lament the nursing shortages that plagued hospitals during the epidemic). It is almost as though the pandemic never happened.

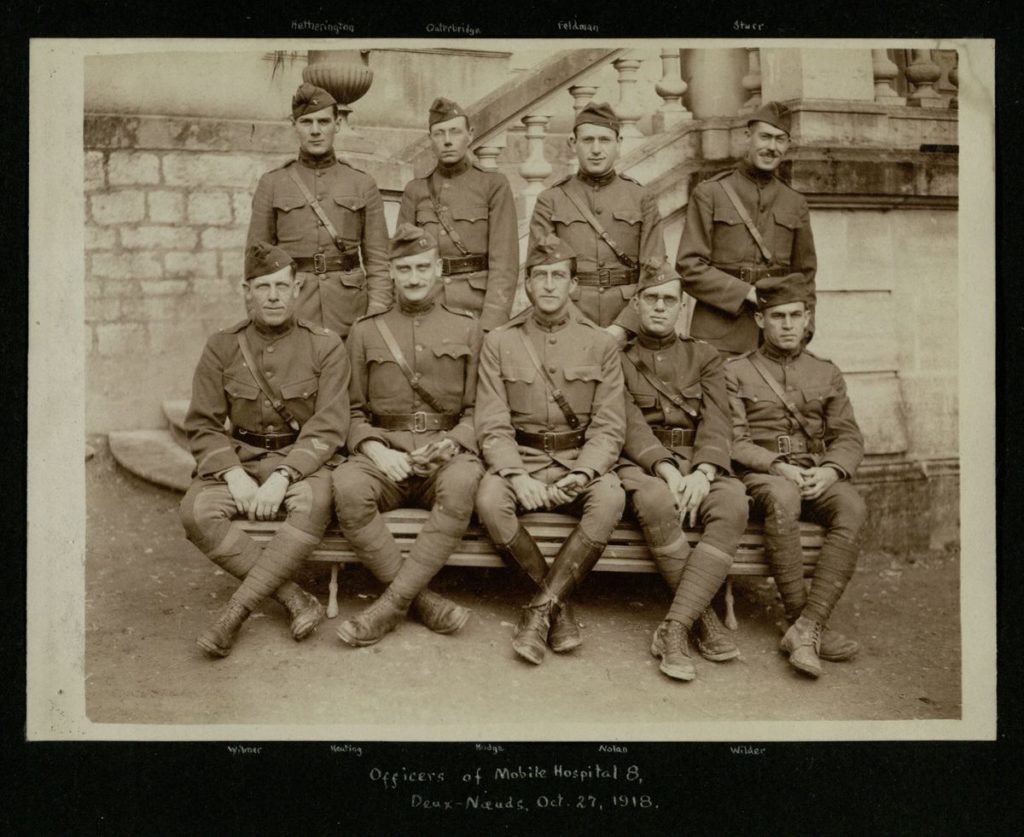

There is no pat answer as to why the pandemic did not merit much official attention of the College. Perhaps it was because of World War I –three-quarters of Philadelphia’s medical staff, physicians and nurses, were already serving in hospitals in France and England by the fall of 1918.

Perhaps this lack of primary sources that we would typically find around an event – the letters, images, and diaries that would document individual or even corporate response to something like the pandemic – is symbolic of a sudden, overwhelming loss of structure, both familial and societal. Five days after the Liberty Loan parade, city leaders in Philadelphia shut down all public institutions and meeting places, even public funerals. Isolation and ignorance combined with rising rates of illness and death, filling Philadelphia residents with a pervasive sense of fear and dread. This shock left people in stasis, unable to process – or document – what was happening at the moment, leaving death certificates as the largest, most complete set of primary sources about the pandemic.

This lack of documentation may also be due to that lack of trained medical staff available in Philadelphia at the time – if you are scrambling for support, medicine, food, and water in the hope of forestalling death, are you going to stop to take a picture, or write a letter?

On September 29, the College will commemorate the 100th anniversary of the pandemic with a day of reflection in the Mütter Museum. In the fall of 2019, the Mütter Museum will debut Spit Spreads Death a permanent exhibit that will highlight that most complete set of extant sources: death certificates. About 20,000 Philadelphia death certificates from 1918-19 will be compiled in a searchable database, available to visitors in a touch map capable of bringing the impact of the past outbreak to present locations (and residents). This dataset will be joined with extant objects and photos, remembrances, public programming, and historical and public health information to form a cohesive chaos that will let visitors explore the fear, loss, and confusion that defined a city in the autumn of 1918. In so doing, the College will create a new material history of the influenza pandemic.

*You can also find this blog post on the College’s History of Vaccines website here.