– by Wood Institute travel grantee Molly Nebiolo*

Samuel Preston Moore was a physician in Philadelphia in the mid-eighteenth century whose surviving letters reveal some of the deep connections physicians had within the Pennsylvania colony. In these letters, we can visualize the networks urban physicians had with more rural areas of the colony. Moore, who later became the provincial treasurer from 1754 to 1768 and was the treasurer of the Pennsylvania Hospital in 1767-1768, is a good example of this because of the rich detail he includes in some of the letters housed at the Historical Medical Library at the College of Physicians of Philadelphia (HML).[1]

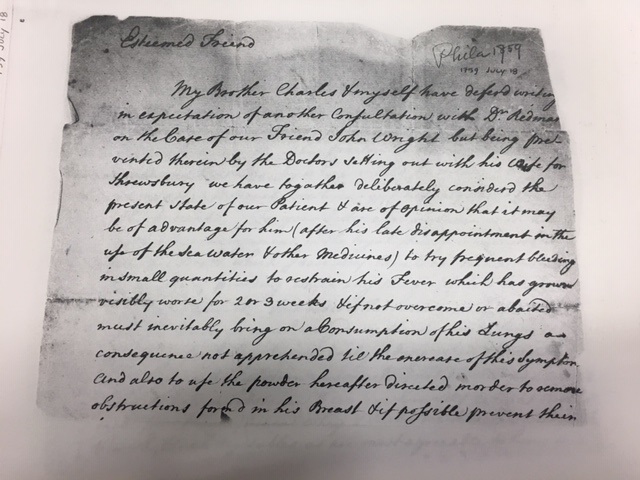

The letters themselves, only a few full-length pieces and a couple of remnants from previous letters, hold a treasure-trove of information about bringing urban medicine to rural populations in the 1750s. One key example of this is from one of his longer letters at the HML, written July 18, 1759, to an “Esteemed Friend” asking for medical advice for his brother, John Wright. In it, Moore is following up with the writer, who seems to have brought his ill brother in for Moore to diagnose, but to no avail. The letter outlines, over the course of several pages, the other doctors he has been in conversation with, deliberating the next steps for trying to heal poor John:

“My Brother & myself deferred writing in expectation of another Consultation with Dr. Redma[n] on the Case of our Friend John Wright, but being prevented therein by the Doctor’s setting out with his chaise for Shrewsbury, we have together deliberately considered the present state of our Patient & are of opinion that it may be of advantage for him (after his late disappointment in the use of the sea water & other medicines) to try frequent bleeding in small quantities to constrain his fever which has grown visibly worse.”[2]

Here we see how interconnected the medical work was in eighteenth century Philadelphia: Moore notes at least two people, Dr. Redman and his brother, who were asked how the patient should be treated.

The letter continues, with an elaborate explanation to the receiver of the letter of why John Wright should take to bleeding to be relieved of his weeks-long fever.

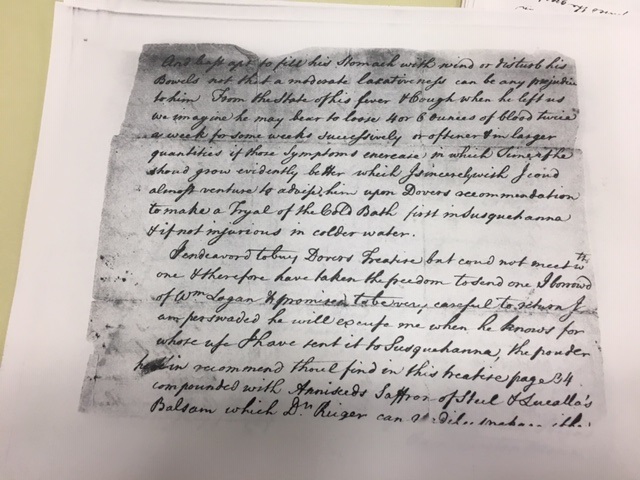

“This method may perhaps appear new but dangerous diseases require powerful remedies and notwithstanding its singularity was used & recommended by Doctor Dover a man of great [note] in his day and well from the success as novelty of his practice in Consumptive & other dangerous Diseases by which indeed he earned the [..] of some of his Medical Brethren yet happily saved the lives of his patients. For your better acquaintance with his method & encouragement in the toil these of I herewith send you his Book which I dare say thou’ll not think much of the trouble of perusing while anything useful & is likely to be collected from it.”[3]

From this quote, we see that Moore even decides to send along a copy of Dr. Dover’s book, to aid in the recipient’s understanding of what he should do to help his brother, but also to explain to his friend why this “novel” method should be attempted on Wright. Interestingly, the book he sent over is not his own copy, but one he borrowed from his friend, William Logan, whose library was vast and his collection of medical and scientific texts nearly complete for the early modern period. “I endeavored to buy Dover’s Treatise but could not meet with one & therefore have taken the freedom to send one I borrowed of William Logan and promised to be very careful to return. I am persuaded he will excuse me when he knows for whose use I have sent it to Susquehanna.” Moore’s letter illustrates not only the connections he has as a doctor, through his casual attitude toward lending out someone else’s book, but also his attempt at trying to educate the letter recipient so they can heal their brother. While physicians in eighteenth century Philadelphia were quite mobile themselves, moving within the city to the immediate countryside to visit their lands or the farms of patients, it was a stark reality that anyone living farther away from Philadelphia would need to rely on home remedies and the knowledge of their wives, servants, or slaves, if anyone became ill. The improvement of postal services allowed for physicians in the city, like Dr. Moore, to gain employment farther outside of the city, but also to build up connections and provide medical advice to those who were in rural areas.

The rest of the letter explains more of what John’s day-to-day life should be until he is completely rid of the fever, including the consumption of broths and snails, taking to the waters in Susquehanna, and going out for a ride if the weather is fair.

Through the detailed examination of this rich letter by Samuel Preston Moore, we get a closer glimpse at what organic relationships between doctor and patient, as well as urban and rural medical communities, might have been like in 1750s Pennsylvania. Not only was medicine a very social practice, with Moore citing four other doctors’ ideas, suggestions, and writings, but it was one that extended outside of the borders of Philadelphia proper. This letter is just one example of the way personal letters of physicians can shine a light on the practices of early colonial medicine. This collection of letters at the Historical Medical Library, among others, provide some of the richest materials for medical humanists to use to better understand the past on a social, cultural, and even economic level.

Sources

[1] The History of the Pennsylvania Hospital, 1751–1895 (Phila., 1895), p. 486; PMHB, xxi (1897), 499; Charles P. Keith, The Provincial Councillors of Pennsylvania (Phila., 1883), p. 74. Sources collected from https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-04-02-0101#BNFN-01-04-02-0101-fn-0001-ptr

[2] Moore, Samuel Preston. Philadelphia, Pa., to “Esteemed Friend.”, 18 July 1759. MSS 2/293

[3] Moore, Samuel Preston. Philadelphia, Pa., to “Esteemed Friend.”, 18 July 1759. MSS 2/293

*Molly Nebiolo is a Ph.D. Candidate at Northeastern University. She received an F.C. Wood Institute Travel Grant from the College of Physicians of Philadelphia in November 2019.