by Wood Institute travel grantee Bryce Evans

Many people dislike airline food, but that was what brought me to the College of Physicians as a Wood Institute scholar (‘Woodie’)! In the literal sense, the airline food on the American Airlines flight over from London wasn’t bad … I’ve certainly had worse. But the reason for my trip was to further research the scientific history of airline food – certainly a niche topic, but one which is pretty universal and always sure to elicit strong opinions.

My time at the library was spent researching diet and nutrition in the early age of aviation. In ensuring the comfort and wellbeing of passengers and crew, much attention was paid to suitable foodstuffs to consume while airborne. I gained a fascinating glimpse of how theories developed around how the human body copes with altitude, air pressure, turbulence, lack of oxygen, and airsickness and specific thoughts on the gastro-intestinal processes attached to these.

One has to remember that flying is a very recent human experience. Although most people these days have been in an airplane at least once, until recently flying was once the sole preserve of an elite (largely white male) few. Scientists longed for more detail on the short and long term effects on the body, how palatable food could be served in the air, and what the effect was of eating a meal at such altitude.

Of course, much of the material in the library concerns an earlier period, and there were some interesting bits and pieces on those ‘mariners of the upper atmosphere’, the 18th and 19th century balloonists who pioneered understanding of what happened to the body when headed for the clouds.

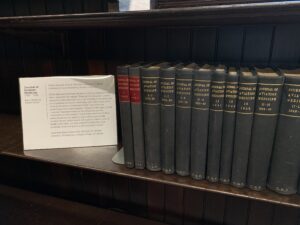

However, the most valuable resource was the complete set of The Journal of Aviation Medicine, spanning the 1920s to the 1960s. This was a treasure trove, with numerous articles relating to my topic. For example, authors explored themes such as the effect of altitude and oxygen upon primary taste perception, learning how the taste perception of sweet, salt, sour and bitter changes at 25,000 feet. These pioneering studies helped the major airlines to innovate around airline food, working with culinary professionals to develop suitable menus. Although many people deride airline food, the production of half-way appetizing food in the circumstances was, if not quite miraculous, underpinned by hard science.

These were the early days of aviation and much of the material is ‘of its time’: writings on the topic were heavily gendered and racialized and often geared towards the strategic priorities of the US Air Force as the USA headed towards entry into the Second World War and post-war global dominance. Similarly, much of the early experiments into diet and digestion in the air would not meet ethical standards of research today. Nonetheless, it is interesting to chart the development of scientific insight around diet, nutrition and flying. These discoveries were of great use later on as the space race developed during the Cold War and astronauts’ diet assumed great importance. Space food owes a huge debt to airline food.

What’s clear from the material is that, in many ways, aircraft in the early days were flying laboratories where the endurance of the human body was put to the test. Airlines were keen to maintain the physical and physiological efficiency of their crew. At the same time, early aviators were very much the ‘guinea pigs’ when it came to research into airborne diet.

Gastrointestinal considerations were integral to the new science of aviation medicine, which examined phenomena such as pressure breathing, cardiovascular and respiratory dynamics, body temperature responses and – in terms of preventive medicine – longer term disease factors precipitated by the new phenomenon, and career choice, of global air transportation.

To research in such august surroundings was a pleasure. I spent many contented hours in the Gross Library and the Norris Library and the behind-the-scenes glimpse at The Stacks was about as fun as it gets for a professional historian. I’d like to express my sincere thanks to Kristen, Shirley, Mary and Heidi: they were always helpful and always good company, and I’m proud to have worn the yellow lanyard and to have been a ‘Woodie’ for the week!

“Influenza and Epidemic Pneumonitis” from Medical Council

“Influenza and Epidemic Pneumonitis” from Medical Council History of United States Army Base Hospital No. 20

History of United States Army Base Hospital No. 20