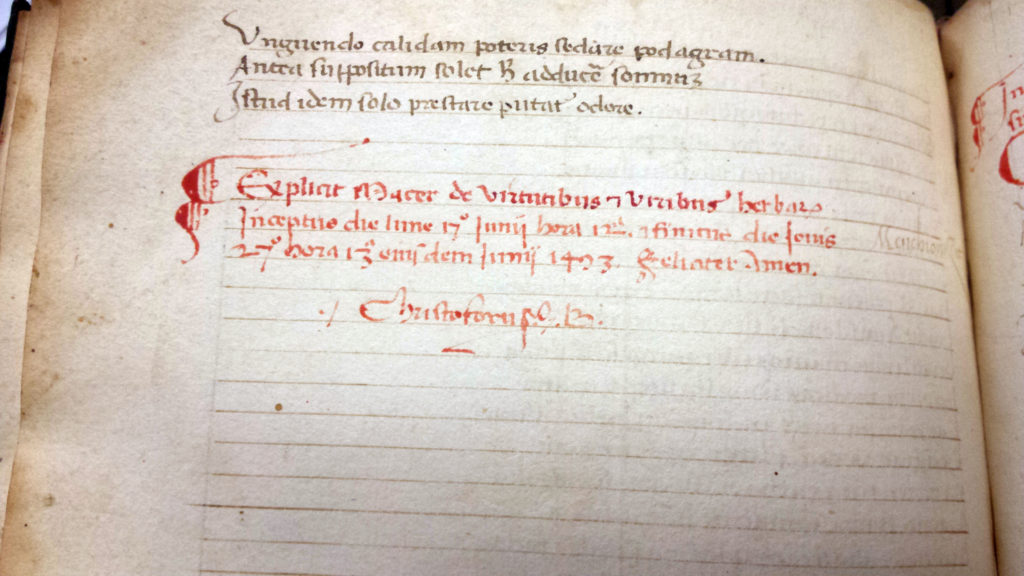

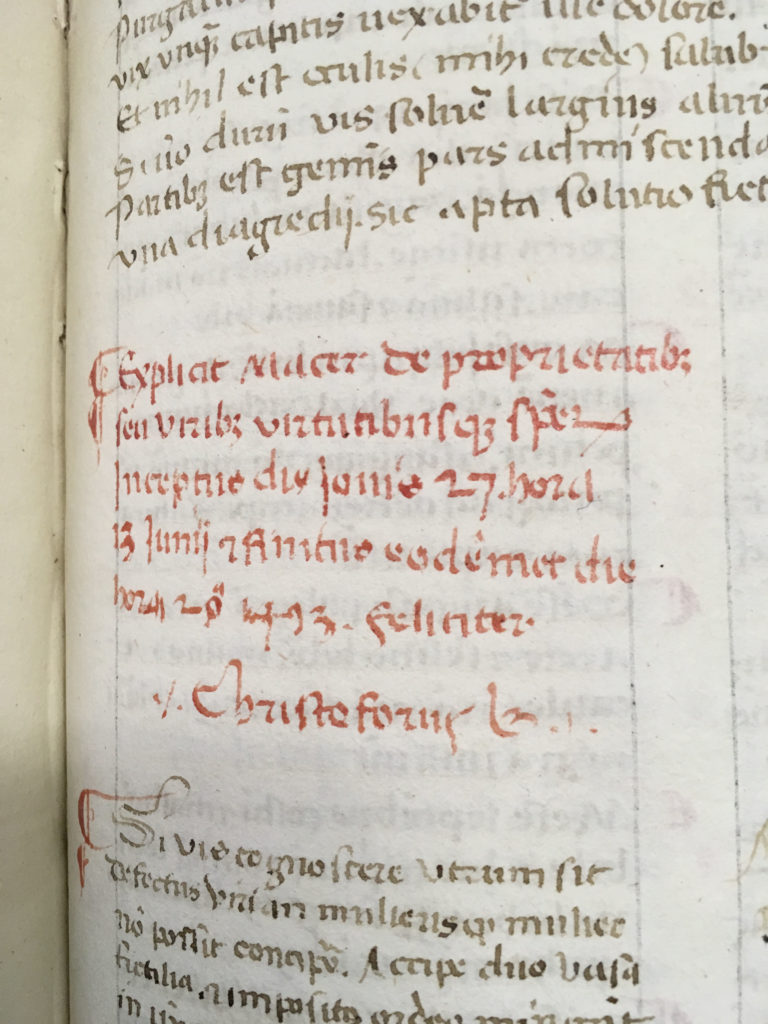

Dating medieval manuscripts can be tricky, as many of them aren’t dated by the scribe, nor do we know who the scribes were. However, 10a 159, Macer Floridus’ De Virtutibus Herbarum, has both a date and a name. We even know approximately how long it took our scribe to complete each section!

#MedievalMonday

“Neither the rose nor the lily may overpass the violet”

Just in time for spring, we’re having a look this week at a medieval herbal and exploring the medicinal properties of the violet. 10a 159 is 15th century Italian manuscript and contains Macer Floridus’ De virtutibus herbarum, among other texts.

A bull in a book

Although 10a 215 was produced in England, the scribes made use of imported paper for Parts II and III. How do we know? From the watermark that is visible on the pages. Below is what the watermark would have looked like before the sheet of paper was folded.

“Her begynnyth the wyse boke of maystyr peers of Salerne”

So begins the last part of 10a 215. The Wyse Boke of Maystyr Peers of Salerne is a 14th-century English medical text, and includes sections on the four humors, signs of deaths, herbs, and recipes. According to a 1993 article by Carol F. Heffernan, the book is attributed to a Peter de Barulo, who lived England in and around 1387. By all accounts, it seems to have been a popular and well-known book, so it’s not surprising that a copy of it ended up in 10a 215.

Manuscripts used as WHAT?!

Yes, Virginia, there is such a thing as ‘manuscript waste.’ To us, several hundred years later, it seems a horrible thing. However, it was common practice for early bookbinders to cut up and use pages from unwanted manuscripts as binding material. These pages were sturdy and were used for paste-downs, wrappers (covers), spine-linings, or gathering reinforcements. Not only did the practice essentially recycle texts that were outdated, damaged, or for some other reason, no longer used, it also gives us an opportunity to get a glimpse into the history of a specific text’s use. If we think about it, it’s not too much different than how we treat old newspapers today: as decoupage, potty-training mats for puppies, packing material, etc., etc., etc.

There’s beauty in limp vellum covers*

“Can you give this a look-over?”

Just like modern-day scholars have trouble reading some texts in medieval manuscripts because the handwriting is poor or sloppy; water-damaged, flaking, or torn; in a difficult dialect; or highly abbreviated, so too did medieval scribes. Texts were copied from an exemplar, and it was not uncommon for slight changes to exist among copies from the same manuscript. This could be due to line-skipping, the inability to read a word, or numerous other reasons.