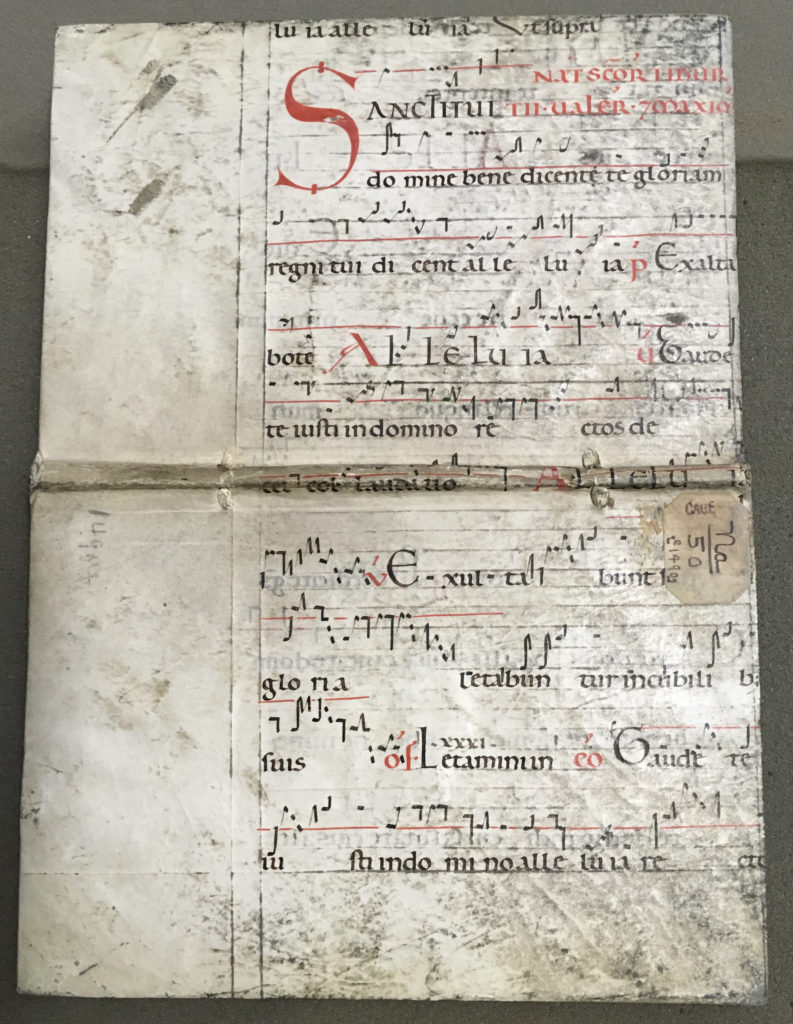

Medieval monks were expected memorize all 150 psalms, and they were commonly sung as part of Mass and the Divine Offices. The music on this binding appears to be part of Psalm 56: “Misit de c[a]elo et liber[avit]…”.

Medieval monks were expected memorize all 150 psalms, and they were commonly sung as part of Mass and the Divine Offices. The music on this binding appears to be part of Psalm 56: “Misit de c[a]elo et liber[avit]…”.

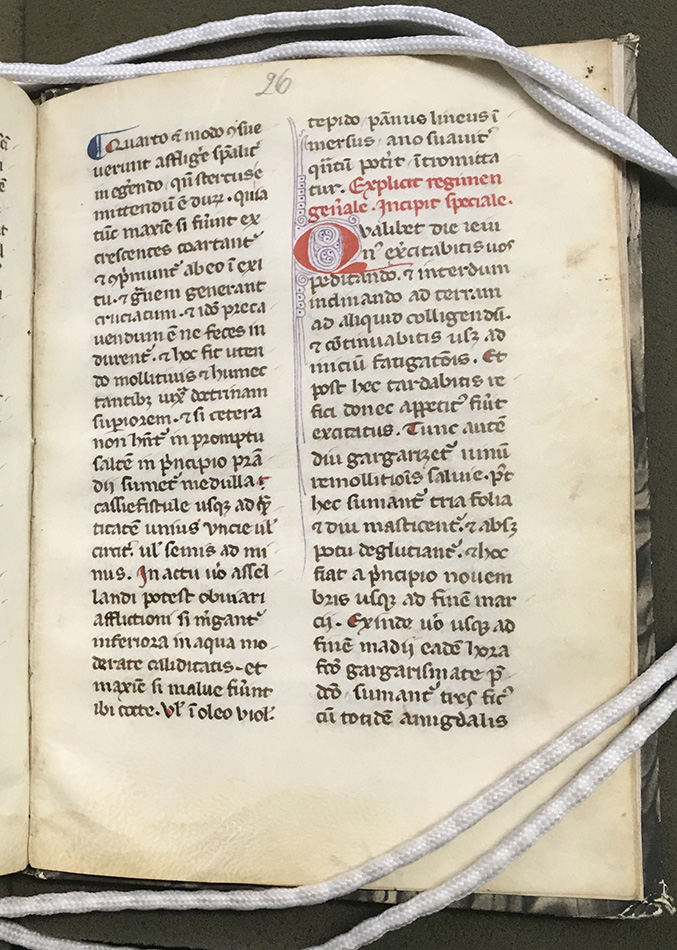

This manuscript dates to circa 14th century, based on the script (a Gothic book-hand), and the composition of the actual text.

The volume was catalogued in our system with the note “Bound in a leaf from a medieval Latin ms. (paragraph marks supplied in alternating red and blue, and capital strokes supplied in red) of a religious text on purgatory; over paper boards.” Even without the acknowledging the script, a text referring to purgatory gives us a place to start, as the word purgatorium is believed to have first appeared in the 12th century.

It’s hard not to have favorites when working in a special collections setting. While searching through our incunabula, I found one bound in a manuscript that I had not seen previously. This particular wrapper has now become one of my favorite items in the collection, and one that I intend to continue researching when time and other duties allow.

Remember all the way back in January – the first #MedievalMonday post – when we met Z10 76 (Constantinus Africanus’ Viaticum), and that I mentioned it was the oldest thing in our collection until a few weeks ago? Well, this week, we will meet the oldest thing in our collection. It’s a binding.

The College holds just 10 medieval manuscripts (or those created before 1500), and we’ve explored many features of ALL of them over the past 10 months. In the next few weeks, I’ll be showing off some of our incunabula (books printed before 1500) that were bound in manuscript waste. Yes, not only were ‘old’ manuscripts used as binding support material (see this earlier post), but they were also used as covers.

It was common practice for early bookbinders to cut up and use pages from outdated or unwanted manuscripts as binding material. This practice lasted until the 17th century, when unwanted manuscripts became more difficult to find.

The College holds at least 4 incunabula bound in music manuscripts, and several others bound in text manuscripts. The next few weeks we’ll be looking at some of them.

As part of its partnership with the Medical Heritage Library, the Historical Medical Library (HML) of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia has completed a National Endowment for the Humanities-funded initiative Medicine at Ground Level: State Medical Societies, State Medical Journals, and the Development of American Medicine, 1900-2000.

The Medical Heritage Library has released 3,907 state medical society journal volumes free of charge for nearly 50 state medical societies, including those for the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico, through the Internet Archive (http://www.medicalheritage.org/content/state-medical-society-journals/). The journals – collectively held and digitized by Medical Heritage Library founders and principal contributors The College of Physicians of Philadelphia; the Center for the History of Medicine, Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine; The New York Academy of Medicine Library; the Library and Center for Knowledge Management at the University of California at San Francisco; the National Library of Medicine of the National Institutes of Health; the Augustus C. Long Health Sciences Library at Columbia University and Columbia University Libraries; and content contributor the Health Sciences and Human Services Library, University of Maryland, Founding Campus, with supplemental journal content provided by the Brown University Library, the Health Sciences Library of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, the University of Pittsburgh Health Sciences Library System, and UT Southwestern Medical Center Health Sciences Digital Library and Learning Center – consist of almost three million pages that can be searched online and downloaded in a variety of formats.

As I mentioned in “A kingly rule of health,” Arnald included a chapter specially for James II on hemorrhoids, which the king suffered from. Arnald advised the king to follow a moderate and healthy diet, staying away from foods that were too salty or sweet, since those foods could cause flare-ups.