– by Jessica Sara Sternbach*

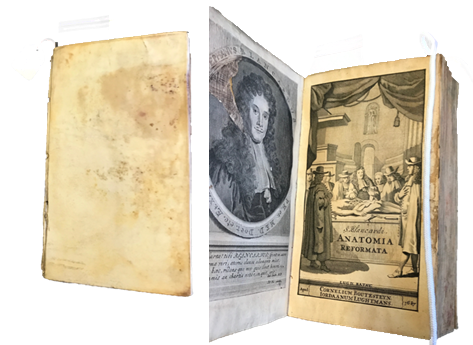

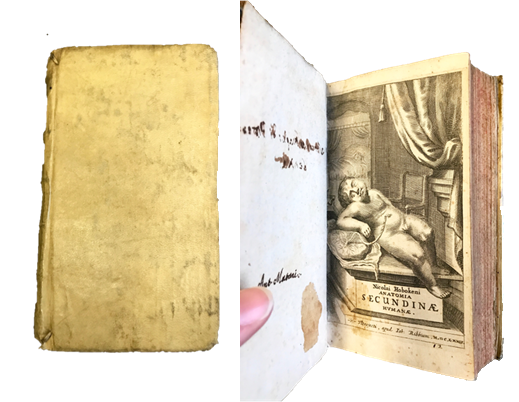

The frontispieces and title pages of early anatomical texts served as teasers for many Early Modern readers, offering the primary information necessary to engage with the text. Once the spine was cracked opened, the viewer would encounter these new medical ideas for the first time, whether it be the authority of a post-Vesalian anatomist as in the Anatomia reformata by Steven Blankaart (1695), the philosophical prowess and artistic pride of William Cheselden and Gerard van der Gucht’s Anatomy of the Human Body (1740), or the sublime awe of the embryology of Nicolaas Hoboken’s Anatomia secundinae (1675). The illustrations in these books drew upon existing visual language in order to decrypt the unfamiliar medical subject matter. Mastery was needed from both the artist and the anatomist, who were trying to comprehend and clarify what it meant to be human.

The three books noted above, from the collections of the Historical Medical Library, all contain frontispieces or title pages with a shared artistic motif: a curtain hanging from the top and tucked just out of frame (figs. 1-3). This motif introduces the notion of revelation, visually linking the stripping of the skin of a cadaver to the opening of the book. In the act of opening the page, the viewer has simultaneously pulled back the curtain and agreed to be a part of the scientific endeavor. Two of the examples, Anatomia reformata and Anatomia secundinae, reinforce this point because both books are bound in a light, flesh-colored, vellum. This makes the act of peeling open the covers analogous with the act of dissection itself. The curtain also creates ties to the anatomy theater where the dissection displayed in Anatomia reformata is occurring.

W. Cheselden. The anatomy of the human body, The XIIth edition. London, 1784. Call no. Gross Ac 4k.

Beginning in the late thirteenth century, human dissection occurred within temporary wooden structures consisting of four steps of circular benches centered around a table, all of which were dismantled at the end of a course.[1] The University at Padua built its permanent theater in 1594, and the University of Leiden followed shortly thereafter in 1597 under the supervision of then professor of anatomy Peter Pauw, who modeled it closely after its predecessor.[2] These permanent structures kept curved rows of seats as “serrated ranks.”[3] This structure not only supported the academic hierarchy, affording the best views to the highest-ranking academicians, but also regulated behavior and helped to keep order at events where the public could attend in large numbers.[4] The first cadavers were usually “unveiled” during carnival season. The reasoning behind this schedule, Andrea Carlino postulates, was three-fold: firstly, it was the coldest time of the year which would ensure the best preservation of the cadaver; secondly, members of the university, including students and professors, were not in coursework and could be in attendance; finally, there was a certain tolerance during carnival given to those activities generally considered transgressive.[5] The veiling of the cadaver before the start of the procedure makes another act of revealing possible. The anatomist pulled off the veil and peeled back the skin. In a simultaneous act, the artist of the frontispiece metaphorically pulled back a curtain as the reader peeled open the cover. Sensory details like these give the illustrations an experiential quality and the reader a sense of authority normally reserved for the anatomist.

The central position of the anatomy professor within the anatomy theater gives him substantial gravitational pull and visually reinforces his authority.[6] The title page of Anatomia reformata visualizes a more intimate dissection, with only a few gentlemen in attendance. However, artists would have been more familiar with the large-scale spectacles held in anatomy theaters. A more chaotic scene around human dissection occurs on the title page of one of the most famous illustrated anatomical books, Andreas Vesalius’ De humani corporis fabrica (1543) (fig. 4). In this book, Vesalius took it upon himself to correct the mistakes of the ancient writer Galen, who based his knowledge of human anatomy mostly on animal dissection, while Vesalius studied human anatomy based on human dissection.[7] The artists of both Anatomia reformata and De fabrica built their scenes around the structural hierarchy of the anatomy theater. The anatomist stands at the center of both compositions with a commanding presence, as if they are instructing the viewer from the page.

Though the curtains hanging above the frontispieces of Anatomy of the human body and the title page of Anatomia secundinae do not reveal scenes of human dissection, the engravers drew upon the visual language of the anatomy theater to give their individual illustrations a connection to the source from which their knowledge was derived. All four images referenced above present a bisected scene with an elevated table where the body is laid out. The higher position of these tables recalls the eminence of ancient sacrificial altars. The inscriptions carved into the stones liken the authors of these books to the ancient deities awaiting to partake of the sacrifices offered on their table. The artists of these frontispieces and title pages have borrowed the spectacle of the anatomy theater through the use of the billowing curtain tucked out of frame and the ancient sanctity of the sacrificial altar to focus their viewers on the body that will be visually dissected in the following pages.

Sources:

[1]Kusukawa, Picturing the Book of Nature. 195; Saunders and O’Malley, The Illustrations from the Works of Andreas Vesalius of Brussels. 42. French, “Berengario Da Carpi and the Use of Commentary in Anatomical Teaching.” 43

[2] Sawday, “The Fate of Marsyas: Dissecting the Renaissance Body.” 130-31

[3] Petherbridge et al., The Quick and the Dead. 38

[4] Cynthia, “Civility, Comportment, and the Anatomy Theater.” 457, 448

[5]Andrea Carlino, Books of the Body: Anatomical Ritual and Renaissance Learning (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999). 81

[6] ibid. 457

[7] Laurenza, Art and Anatomy in Renaissance Italy. 22

*Jessica Sara Sternbach is a Ph.D. student in Art History at Temple University’s Tyler School of Art.