– by Josh Bicker, Visitor Services Floor Supervisor

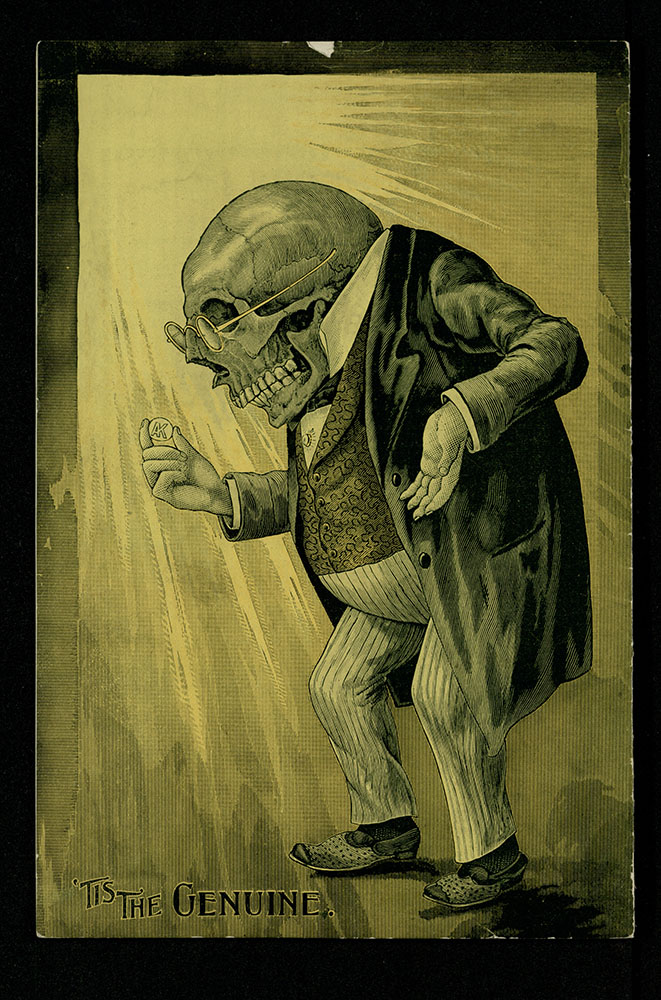

Among the College of Physicians Medical Library’s collection, we have a number of advertisements for the Antikamnia Chemical Company. Within these, a curious image can be found in an advertising pamphlet of the time, portraying a stout man, dressed in a suit, with an enormous skull atop his neck. With spectacles perched at the bridge of his nose, he closely inspects a round tablet with the letters “AK” monogrammed on it. Rays of light shower over him, and at the bottom of the page we see the phrase “Tis The Genuine”. It is as if he has received some divine inspiration.

The divine inspiration he appears to have discovered is an Antikamnia pill, and not just a cheap knockoff, but the real thing. In advertisements for the Antikamnia Chemical Company, the medicine they prescribed were indeed shown as heavenly products, able to cure a number of common illnesses and annoyances of the day.

The Antikamnia Chemical Company was one of many burgeoning drug companies that emerged in the second half of the 19th century. Antikamnia’s biggest ingredient in all their medicines was acetanilid. This white, sparkling powder, derived from coal tar, was discovered in Strasburg in 1886 by two physicians, Cahn and Hepp. In an attempt to destroy a patient’s intestinal worms, they accidently utilized acetanilid instead of the more potent naphthalene. Rather than killing the intestinal worms, the substance instead lowered the patient’s fever. However, its success as a fever reducer intrigued drug producers and physicians, and soon acetanilid was being used to create medications.

In the United States, the substance soon became of interest to two drug store owners in St. Louis. Their names were Louis E. Frost and Frank A Ruf, and although they owned a drug store, there is no proof that they were licensed pharmacists. In 1890, they established the Antikamnia Chemical Company. Antikamnia translates to “opposed to pain” in Greek, and with the help of acetanilid, they attempted to cure everyone’s aches and pains.

Pills were made to combat toothaches, the flu, and headaches, as well as more serious illnesses such as typhoid and meningitis. They were frequently mixed with other substances such as codeine, quinine, heroin, and laxatives to make them more effective. In an ad from the time, they recommended taking a pill before doing anything headache inducing, such as shopping, light exercise or even going outside.

This cure-all medicine was heavily boosted by efficient and creative marketing. The Antikamnia Chemical Company’s main buyers were drug stores, rather than personal customers. In order to interest them, they sent out numerous mailed advertisements to both drug stores and physicians, who could both prescribe their medicine. In this, they are recognized as early innovators in the “junk mail” field. These advertisements contained many perks, including postcards, illustrated medical charts as well as calendars.

Among the most famous calendars are the ones created by Dr. Louis Crusius. His work is where we get our main image from. Crosius was born in 1862 in St. Louis, and he was the oldest of nine children. He became an apprentice printer under his father, who published the Pioneer Press Daily. Leaving behind his printmaking routes, he instead studied pharmacy, and after receiving his degree, he started a drug store with his brother, Gustav H. Scheel, known as Scheel & Crosius.

Even while working as a pharmacist, Crosius still pursued his artistic interests. He created a number of satirical drawings of professional men with the well-known skull heads, and he exhibited them in the windows of his drug store. These images were meant as a light-hearted, satirical look at the medical profession, with images of skull-headed medical professionals treating patients, mixing drugs, and diagnosing illnesses. They served as a macabre but amusing reminder of the permanence of death despite anyone’s attempts to thwart it. Crosius’s illustrations went on to portray a number of people in different walks of life, from babies to cowboys, all with the ever present, but lighthearted reminder of death around the corner.

In 1893, he published “Funny Bone”, a collection of 150 illustrations and various jokes. Soon after, he went on to sell a number of his illustrations to the Antikamnia Chemical Company. They went on to create calendars with his images, and from 1897-1901, they included these in the mailings they sent to physicians and drug stores.

The Antikamnia Chemical Company went on to be successful until 1906, when the Pure Food and Drug Act was passed. Acetanilide, the company’s magic ingredient, had before this been found to be poisonous and habit forming. However, ingredients of their pills had not been revealed to the public. With the Act of 1906, their ingredients were exposed, and the company quickly disintegrated.

Despite the collapse of the Antikamnia Chemical Company, the advertisements, postcards and calendars are still collected and appreciated to this day, in particular those of Louis Crosius. His weird, charming illustrations, with their skull-headed physicians, are not only interesting to look at, but may have also unwittingly foretold of the long-term poisonous nature of the Antikamnia Chemical Company’s medicines. They divulge to us the fine line that existed between quackery and medical science in the 19th century.

Sources:

Adams, Samuel Hopkins. “The Great American Fraud: Articles on the Nostrum Evil and Quacks, Reprinted from Collier’s Weekly” American Medical Association, 1907. https://archive.org/details/greatamericanfr02adamgoog/page/n46/mode/2up.

“Acetanilide”. Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/science/acetanilide.

Angelone, Caitlin & Dahn, Tristan. “Bad Medicine: Drug Manufacturers, Advertising, and the Push to Sell” Historical Medical Library of The College of Physicians of Philadelphia: Digital Library. https://www.cppdigitallibrary.org/exhibits/show/bad-medicine/.

“The Antikamnia Calendar for 1900” Deborah Colthman Rare Books. https://www.dcrb.co.uk/book/3268/patent-medicine-antikamnia-chemical/the-antikamnia-calendar-for-1900/ Accessed 11 Jan. 2020.

Brune, Kay & Hinz, Burkhard. “The discovery and development of antiinflammatory drugs” Arthritis & Rheumatism, Vol. 50, No. 8, 5 Aug. 2004. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/art.20424.

Graves, W. H. “The Dangers of Acetanilid” JAMA Network Vol XLV, No. 4, 22 July 1905. http://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1905.02510040024010.

Johnson, Russel. 1908=2020. UCLA Library: Library Special Collections Blog. 6 Jan. 2020, https://www.library.ucla.edu/blog/special/2020/01/06/1908–2020.

Schatzki, Stefan. “The Diagnosis”. American Journal of Roentgenology, Vol. 182, no. 3, March 2004. https://www.ajronline.org/doi/pdf/10.2214/ajr.182.3.1820616.

Straight, David L. “Against Pain”. The Confluence, 2009. https://www.lindenwood.edu/files/resources/the-confluence-fall-2009-straight.pdf.