It’s been just over a year since COVID-19 shut down most of the world, including the United States and Philadelphia. The value of libraries and funding them has always been a hot topic, but with libraries shuttering their doors during the early days of the pandemic, it is even more obvious just how much our communities rely on libraries. In my eyes, there is no disputing the value of public and school libraries (see Further reading at the end for some great articles, including one written by Neil Gaiman!) – they do so much more than “just” lending out books.

A recent article published in the Philadelphia Inquirer, “Free Library is understaffed, undervalued and budget cuts won’t help”, discusses the issues that many libraries have faced over time: lack of staff, lack of funding, and lack of support. The Free Library of Philadelphia is a valuable resource to all of the neighborhoods and communities it serves, including the scholarly community which makes use of the main branch’s Rare Book Department. The Rare Book Department serves as an example of special collections libraries – which may not be as familiar as public libraries, but face the same problems of lack of resources. So what are special collections libraries?

Special collections libraries can be part of universities, colleges, public libraries, or non-profit organizations like The College of Physicians of Philadelphia. These libraries have materials that are rare and often unique (existing only in one place), often have extra security, and require researchers to make appointments to use their collections. Usually, a special collections library will focus on one or very few subjects – at the Historical Medical Library (HML), our collection focuses on the history of medicine.

Many special collections libraries, like the HML, have “closed stacks,” meaning only library staff can browse the shelves and pull materials for use. This is because the materials are rare or unique, sometimes very fragile, and require a cool, dark space in order to stay preserved. Generally, books and other materials found in special collections libraries can’t be checked out – they have to be used in the library’s reading room.

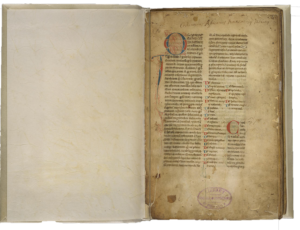

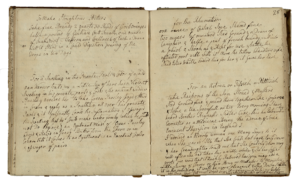

Materials in special collections libraries may include rare books, medieval manuscripts, photographs, lantern (glass) slides, film reels, video cassettes, audio cassettes, diaries, manuscript (handwritten) recipe books, lecture notes, correspondence, scrapbooks, and other papers.

The HML’s collection includes all of these types of materials, and our oldest book dates to the early 13th century. The HML was established in 1788, just a year after The College itself was founded in 1787. In December 1788, John Morgan — a founder of both the College and of the first medical school in the United States (now the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine) — donated sixteen volumes. Other Fellows soon followed Morgan’s example and before long the College allocated funds to purchase books, bind them, and erect a bookcase to hold them.

Today, the HML holds about 2,300 linear feet of manuscript collections and College archives; over 375,000 volumes of journals, books, and rare books, including over 400 incunabula (books printed before 1501), and the largest collection of confirmed anthropodermic books (books bound in human skin) in the country. HML staff work with over 550 researchers a year (combined in-person and via email or phone), and our researchers range from humanities students, independent scholars, professors, scientists, physicians, medical students, artists, and writers. We curate digital and physical exhibits, working closely with the Mütter Museum and the Center for Education; host pop-up exhibits for special College events or local university classes; offer internships to students in graduate-level library science programs; participate in consortia grant-funded projects, like For the Health of the New Nation… – and that’s all in addition to preserving, cataloguing, and rehousing our books, pamphlets, and manuscripts so that researchers now and in the future can discover and make use of our collections.

But what value do all these old books and manuscripts have? Why is it important to care for them and make them accessible for people to use?

These resources help us understand the present by understanding the past. They helps us connect events, people, and cultural traditions that came before us to the world in which we currently live. For the HML’s collection specifically, the history of medicine helps us gain a deeper understanding of our society.

Ads for prescription medicine in medical journals during the early second half of the 20th century give us insight into the way women and women’s healthcare were viewed. A longitudinal study of Civil War soldiers who had a leg or an arm amputated allow us to see the long term effects of war wounds and amputations on the human body and mind. Letters written by doctors who served in France during World War I detail the devastation the fighting had on the civilian population as well as those working behind the lines caring for the soldiers. Lecture notes and recipe books on the use of herbal remedies help us trace the advancement of medicine.

So maybe now you’re convinced that these historical materials are useful and valuable to us today. But why not just digitize them all? After all, it’s the information they contain that we’re interested in, right? Maybe in a few cases sometimes, but for the sentimental types, there’s no replacing the feel of 16th-century rag paper; the smoothness of parchment bindings; indentations and raised letters caused by early printing methods; or that homey old book smell. But there are many important things these old materials have to tell us that cannot be translated to the digital realm: the chemical composition of inks or a stain on a page; the DNA of the animal used to make the parchment page or leather binding; the bacteria or viruses left behind by an earlier reader; and past bookbinding techniques – to name a few. (Who knew?! Well, librarians, archivists, curators, historians, scientists…)

While all of the above statements are true, it’s also true that without people using these materials – reading stories to escape the world, performing scientific analysis, or going through historical records to inform the future – these materials lose their sense of purpose. I can talk about the value of books, photographs, and papers until I’m blue in the face, but you don’t have to take my word for it:

“I’m creating a small exhibition on the visit by Marie Curie to the College in 1921, 100 years ago. It was extraordinary to be able to go into the archives and read all the correspondence between the folks trying to organize the details of the visit. She brought a gift to the College of the Piezo-electric apparatus that was made by her husband Pierre. Much of the discussion was around transporting this very valuable object. I even found this little sketch that described the dimensions of the object so that a suitable carrying case could be constructed.” – Jacqui Bowman, Director, Center for Education; Acting Co-Director, Mütter Museum; Co-Director, Living Exhibits

“The history of American medicine simply couldn’t be written without the College of Physicians of Philadelphia or its Historical Medical Library. Its medical manuscript collections are some of the most important and robust in the country, and illuminate topics ranging from vaccinations to doctors, therapeutics, hospitals, minority groups in medicine, and anything and everything in between. I’m writing a history of opioid addiction in 19th century America, and there’s no way I could have even launched this project without first consulting the archives at the College of Physicians, from which I was able to access extremely rare Civil War-era hospital records. The Library’s resources are invaluable to how we understand the past of American medicine, and its future.” – Jonathan Jones, Postdoctoral Scholar, George and Ann Richards Civil War Era Center, Penn State University

“I advanced to candidacy for my PhD during COVID, so all of my research has been affected by the pandemic. Since I can’t go to archives, I have had to find unique ways to get materials for my research. The Archivist at the College of Physicians of Philadelphia has been particularly helpful. Not only was she attentive and quick with her responses, but she found materials for me that are going to be extremely useful for my research. This is not how I initially envisioned doing research when I started my PhD studies, but everyone at CPP has been so helpful. I now have more material than I know what to do with, which is not a position I thought I would be in, but thanks to CPP it is a good position to be in.” – Miriam Lipton, Ph.D. Candidate, History and Philosophy of Science, Oregon State University

“Fortunately, I was able to visit the Historical Medical Library last October as I was beginning research on one of my dissertation chapters. In particular, I was eager to learn more about the Mütter’s collections of anatomical models. In the archives, I was able to examine committee reports, correspondence, and invoices related to their acquisition, care, and uses. Discovering the paper trail of the models in the Mütter’s collection has helped me better understand how anatomical models were integrated into medical collections and, more broadly, how they were valued in the nineteenth century. The entire staff at the Library have been extremely welcoming and helpful throughout my research. In particular, after COVID forced the Library to close, the Archivist was able to provide me with photographs and scans from the collection that were critical to the completion of my chapter. I look forward to returning to the Historical Medical Library in the near future!” – Kristen Nassif, Ph.D. Candidate, Department of Art History, University of Delaware

“When I began my postdoctoral fellowship this fall I had a very clear vision of what my academic year would look like: Each morning I would walk to the train station very close to my new apartment, which I had rented specifically to make my daily commute to the archives as easy as possible. I would use the short trip to 30th Street to wake up, gather my thoughts, and mentally plan out my day of primary source research. Then, admiring the Schuylkill along the way, I’d stroll over to the Historical Medical Library at the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, and dig in. Then repeat, for weeks or months on end, or however long it took before I exhausted their materials and moved on to other area archives.

I only made this journey twice before Covid restrictions closed local archives to visitors and threw a very annoying wrench into my fellowship plans. While I have made liberal use of digital and off-site services that archivists have heroically adapted to offer patrons during this time, nothing replaces working on-site with historical materials first-hand.

In fact, the nature of my research project requires it. I won this fellowship to conduct research for a book project on the history of physicians’ wives in American medicine. As you might expect, their contributions to their husbands’ careers—though undeniable—are not always easy to discern and are far from self-evident. Their presence is both everywhere and nowhere in the archive. To locate these women in the historical record requires carefully sifting through dozens upon dozens of boxes of materials to find largely uncatalogued and overlooked hints. I cannot simply request photocopies of pre-determined pages in specific folders; I have to go seek something that has not yet been found.

Back in the fall, when I made my appointment and wore my mask to conduct research in-person responsibly following public health guidelines, I started with the low-hanging fruit first: the records of the College of Physicians Women’s Committee. This long-lived group of primarily Fellows’ wives dedicated enormous energy towards the maintenance and revitalization of College facilities, in addition to serving as a sort of social club. Reading their committee minutes and correspondence provided a fascinating look into their important activities, which arguably made today’s College resources possible.

But what about those countless collections of physicians’ personal papers that the Historical Medical Library houses? And the collections dealing with the College’s history beyond the Women’s Committee? My fellowship is coming to an end soon, but I am still waiting patiently for my opportunity to hop on the train and finally see what they have waiting for me to discover. Thankfully, this history will still be there.” – Kelly O’Donnell, Consortium for Science, History, Technology, and Medicine NEH Postdoctoral Fellow

“The Historical Medical Library at the College of Physicians fosters a delightful research community, and their resources in the history of medicine are second to none. For my work, their records of medical educators and students have been integral to illustrating how racial science and the politics of slavery were national rather than sectional. For example, correspondence between Penn Professor Joseph Leidy and Southern doctors in the months immediately before and after the Civil War revealed how physicians’ professional relationships transcended the secession crisis. In short, for scholars like myself, the resources at the College of Physicians of Philadelphia have been essential for writing the history of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century medicine.” – Christopher D.E. Willoughby, Junior Visiting Fellow, Center for Humanities & Information, The Pennsylvania State University

I think it’s safe to say that all libraries are integral to their communities, should be valued as such, and are most definitely here to stay. And that’s good news for book lovers everywhere.

Further reading

“Libraries Are a Refuge in Times of Crisis.” Blog, Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS), 2020, www.imls.gov/blog/2020/03/libraries-are-refuge-times-crisis.

“Rights and Restrictions: Are Library Values Being Respected During COVID-19?” Library Policy and Advocacy Blog, International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA), 14 May 2020, www.blogs.ifla.org/lpa/2020/05/14/rights-and-restrictions-are-library-values-being-respected-during-covid-19/.

Ashworth, Boone. “The Coronavirus’ Impact on Libraries Goes Beyond Books.” Wired, Conde Nast, 25 Mar. 2020, www.wired.com/story/covid-19-libraries-impact-goes-beyond-books/.

Gaiman, Neil. “Neil Gaiman: Why Our Future Depends on Libraries, Reading and Daydreaming.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 15 Oct. 2013, www.theguardian.com/books/2013/oct/15/neil-gaiman-future-libraries-reading-daydreaming.

Harvey, Gillian. “It Took COVID Closures to Reveal Just How Much Libraries Do Beyond Lending Books.” Observer, Observer, 24 Sept. 2020, www.observer.com/2020/09/public-libraries-adapt-to-future-ebooks-digital-community-outreach/.

Hoopes, Erin, and Judith Everitt. “Free Library Is Understaffed, Undervalued and Budget Cuts Won’t Help: Opinion.” https://www.inquirer.com, The Philadelphia Inquirer, 8 Mar. 2021, www.inquirer.com/opinion/commentary/free-library-philadelphia-budget-cuts-mayor-kenney-20210308.html.

Hursh, Angela. “Lessons Learned from Libraries in a Pandemic: EBSCOpost.” EBSCOpost, EBSCO Information Services, Inc., 18 Dec. 2020, www.ebsco.com/blogs/ebscopost/lessons-learned-libraries-pandemic.