– by Patrick Magee, Visitor Services/Gallery Associate

Welcome to another edition of Medieval Medicine Monday! On Mondays, I highlight information found through the Digital Image Library and draw connections between the world of the early teen centuries and the world we have come to know since! Using a mixture of primary sources of original content, alongside more modern academic writing, Medieval Medicine Mondays are a peek into the shared knowledge of the past through the applied knowledge of the present.

In the medieval and early modern eras, treatment of the plague was very touch-and-go due to a relatively limited amount of medical knowledge about both the condition and the immune system in general. In prior issues, we have discussed how medical superstitions came into play during times like these, although there is some evidence that more modern medical techniques were already starting to come into play towards the tail end of the medieval era. Enter prophylaxis.

Prophylaxis is defined as “action taken to prevent disease,” which is understood and applied on both macro- and micro- levels during modern times, although the concept was certainly only coming into its own during the 14th through 17th centuries. What we can now do with pills or intravenous administration used to be more complicated and less successful, but it was the years of trial-and-error dating back to the aforementioned eras that allowed for the science to develop in a meaningful and applicable way (What Is the Definition of Prophylaxis?).

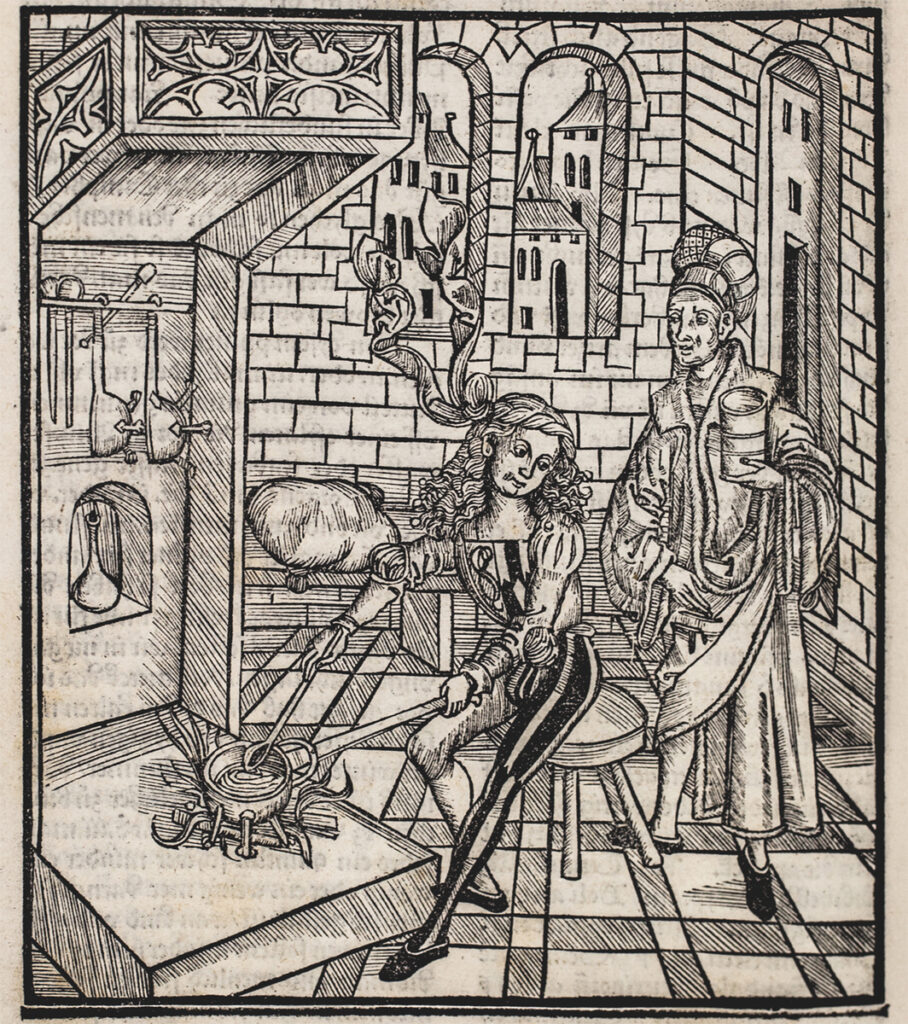

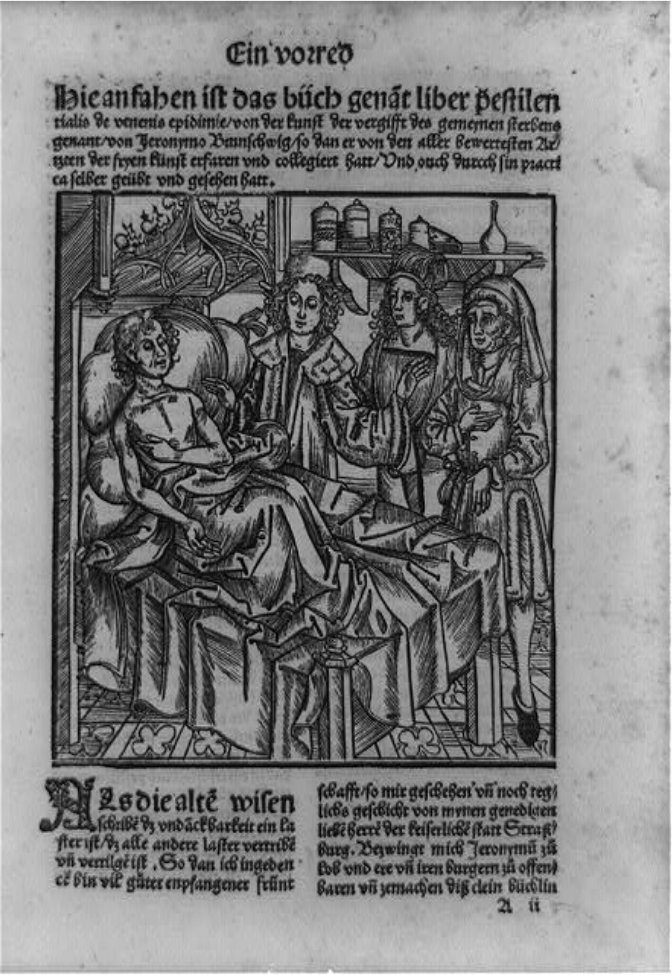

To understand plague prevention, let us first be reminded of the early approach to plague treatment, in order to gain perspective on the common approaches of the era: “Physicians relied on crude and unsophisticated techniques such as bloodletting and boil-lancing (practices that were dangerous as well as unsanitary) and superstitious practices such as burning aromatic herbs and bathing in rosewater or vinegar.” (History.com Editors).

A set of beliefs known as humoral theory often associated with the period (though developed by Greek philosophers) was given additional prominence by figures like William Shakespeare. Humoral theory suggested that interactions between the four humors (black bile, phlegm, yellow bile, and blood) played roles in health history, temperament, aging, and lifestyle. It also supposed that certain geographical residents were more likely to share traits due to shared experiences and environmental factors like temperatures. (“Four Humors – And There’s the Humor of It: Shakespeare and the Four Humors.”) Humoral theory saw real-world application in the form of purgatives and enemas, and became part of the groundwork for medical practice at the time. In practice, this meant attributing the plague to factors like a personal imbalance of the humors, which we now know to be ignorant of the contagious nature of the disease (Mellinger).

It was only the richest of the rich who could even scratch the surface of a modern approach that separates faith and the observable, as explained by Yon Jin Hong and Sam Hun Park’s research on Medieval Paris: “[the Compendium de epidemia prescription written by the Masters of the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Paris in the mid-14th century during the Black Death] seems to have been written primarily for the royal family and nobles who ordered them when looking at prescription-related technologies. At the same time, under the influence of Islamic-Arabic academia, it clearly distinguishes the world of faith and the world of academia (intelligence), explaining the pathogenesis and infection pathways based on causality.” (Hong, Yong Jin, and Sam Hun Park).

The level of wealth and class disparity during the Middle Ages certainly skewed the effectiveness of information and publications like the Compendium. The science was starting to form recognizable patterns, though: diseases were understood to be derived from an environmental factor rather than an act of god; therefore, it could be inferred that diseases could be prevented by adjusting or removing environmental factors or behavior. This is the basis that we use to prevent getting ill in general now, and the most relevant modern example comes to mind in the form of a medical mask. In its essence, this is a form of prophylaxis, just as the same would have been true for a plague doctor (despite the stylistic differences).

One of the other most notable examples of prophylaxis in modern medical science is found in Pre-exposure Prophylaxis, a type of medication that can be used to prevent HIV. Though a cure for HIV has still not been found, treatments are available, and PrEP represents the culmination of years of medical research and applied science. Pre-exposure prophylaxis offers at-risk people around the world another line of defense that they can add to their routine. According to the center for disease control, “Studies have shown that PrEP reduces the risk of getting HIV from sex by about 99% when taken daily.” (“Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP)”).

Once again, history shows us that applied medical science is a matter of building on discoveries and observations over time, rather than seeking otherworldly explanations for worldly occurrences. Diseases can be defeated in part by keeping an eye on the past and repeating what worked, while also accommodating for new information that prevents failures in the future.

Works Cited

“Four Humors – And There’s the Humor of It: Shakespeare and the Four Humors.” U.S. National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health, 19 Sept. 2013, www.nlm.nih.gov/exhibition/shakespeare/fourhumors.html.

History.com Editors. “Black Death.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 17 Sept. 2010, www.history.com/topics/middle-ages/black-death#section_5.

Hong, Yong Jin, and Sam Hun Park. “Medical Care or Disciplinary Discourses? Preventive Measures against the Black Death in Late Medieval Paris: A Brief Review.” Iranian Journal of Public Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Mar. 2017, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5395523/.

Mellinger, Jessica. “Fourteenth-Century England, Medical Ethics, and the Plague.” Journal of Ethics | American Medical Association, American Medical Association, 1 Apr. 2006, journalofethics.ama-assn.org/article/fourteenth-century-england-medical-ethics-and-plague/2006-04.

“Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP).” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 13 May 2020, www.cdc.gov/hiv/risk/prep/index.html.

What Is the Definition of Prophylaxis? www.webmd.com/heart-disease/heart-failure/qa/what-is-the-definition-of-prophylaxis.