– by Wood Institute travel grantee Sharlene Walbaum, Ph.D.*

Imagine this: it is 1750. You work a farm near Philadelphia. Your child, now a young adult, hears disturbing voices, is suspicious and fearful, and sometimes lashes out violently. It is terrible and sad. You feel the weight of responsibility to your child and to others. What are your choices? There are no emergency rooms, mental health care clinics, psychotherapists, or antipsychotic medications.

Families and communities were responsible for someone experiencing mental illness, although the ways in which that obligation was met seem cruel today. If the person was dangerous to self or others, he or she might live chained in a shed or a hole dug in the earthen floor of the kitchen that was covered with a grating. Or, he or she might face a potentially worse fate – jail or the almshouse. If danger was not a concern, he or she might be left to wander out of doors and depend on the kindness of neighbors. Confinement, incarceration, homelessness – how different are options today?

By mid-18th century, doctors were developing new ideas about how to respond when someone was “deprived of reason.” In 1733, for example, Dr. George Cheyne wrote in The English Malady: or a Treatise of Nervous Diseases of all Kinds that air, sun, and exercise is the best treatment. In his view,

“There is not any one Thing more approv’d and recommended by all Physicians, and the Experience of all those who have suffer’d under Nervous Distempers, … than Exercise of one Kind or another… But certainly the best of all is, where Amusement or Entertainment of the Mind is joined with Bodily Labour and constant Change of Air.”

Dr. Willian Cullen, writing in Edinburgh in 1764, offered this prescription for someone living with “nervous ailments”:

I think it absolutely necessary for Mr. Scrimgeour to enter upon a long journey as soon as possible … upon a Road that affords good accommodation & will at the same time present some variety of entertaining objects & amusements…it will be of great service to him to have a Companion that can rouse his attention & direct his Resolution & keep both his Body and mind in motion. (RCPE, 2018)

[Doctor Who, anyone?]

In 1752, scientific advances aligned with religious values and a new option opened in Philadelphia – Pennsylvania Hospital. In 1671, George Fox, founder of the Society of Friends, had written about the “inner light of God” existing in every person (Cadbury, 1948). One’s primary goal is to live a life illuminated by that light, but being “distracted or troubled in mind” impedes one’s access to it. Therefore, others must be compassionate and provide refuge until the afflicted person can again be guided by that light. According to Clark (1951), the Philadelphia Meeting started lobbying in 1707 for a hospital to provide protection and care for citizens suffering from physical or mental afflictions. But it wasn’t until Quaker Dr. Thomas Bond began raising money in 1750 that success became possible. He appealed to his influential friend Benjamin Franklin to help garner support. As a result, George II signed “An Act to encourage the establishment of an Hospital for the Relief of the Sick Poor of this Province, and for the Reception and Cure of Lunaticks” in 1751.

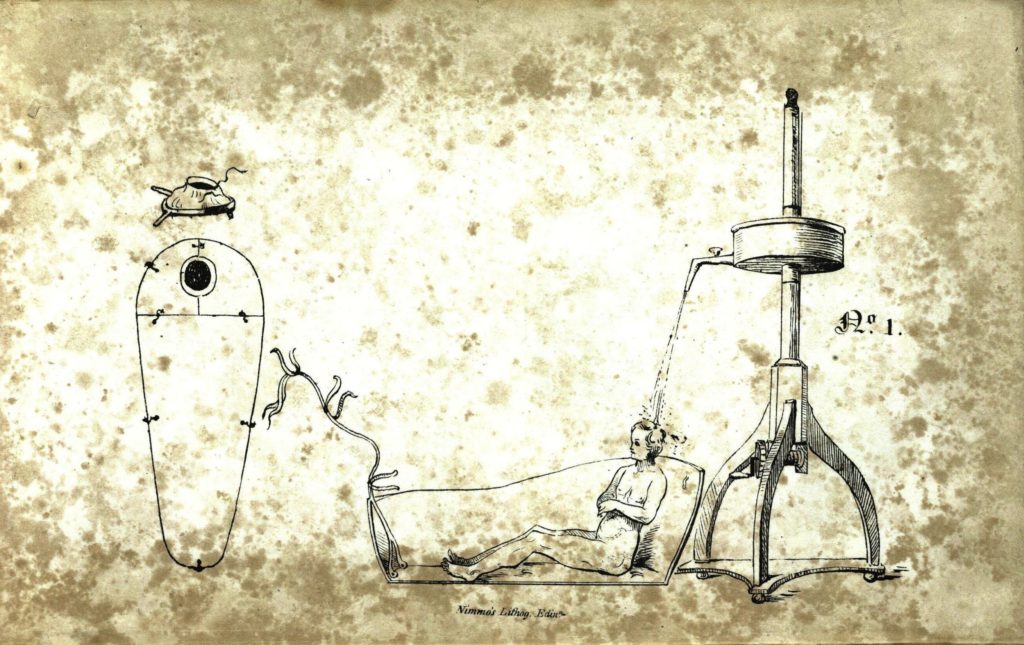

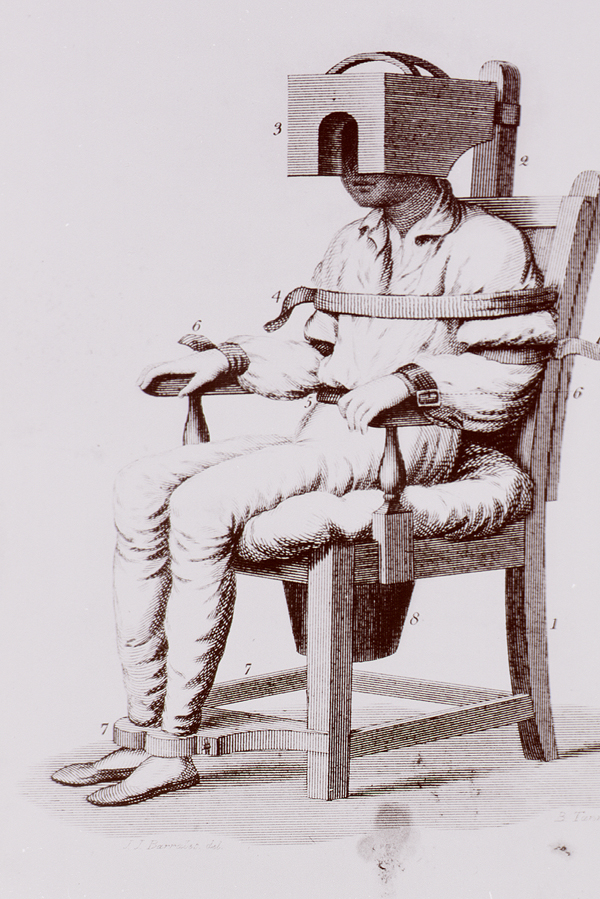

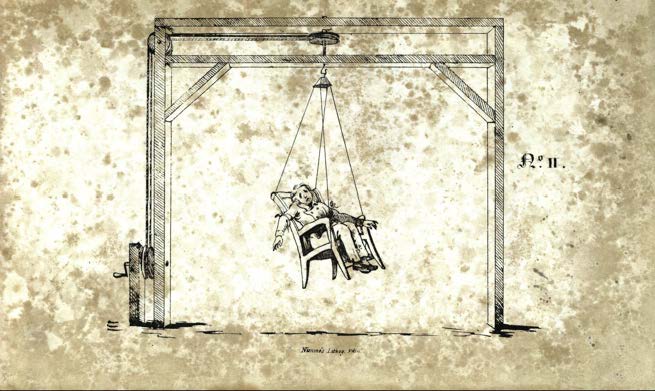

Pennsylvania Hospital became the first teaching hospital in the colonies. Doctors explored various ideas about the causes of mental illness. One, rooted in ancient Greek medicine, was that it was the result of physiology going awry or being out of balance. If a treatment could set it right, the mental illness would go away. Many treatments were based on this premise, but three stand out: the Bath of Surprise, Benjamin Rush’s Tranquilizing Chair, and William Hallaran’s Circulating Swing. Through a sensory shock, sensory deprivation, or centrifugal force, the person’s body could be righted, regain its equilibrium. They were popular treatments during the early years of psychiatry.

By the dawn of the 19th century, Philadelphia Friends were unhappy with Pennsylvania Hospital. It had become large and overcrowded, no longer meeting their goal of helping those who were “distracted in mind” regain access to their inner light. Deciding to establish an asylum based on Quaker values, they patterned their approach on that pioneered in 1797 by William Tuke for York Retreat in England:

“The plan of combining mild restraint and moral discipline with the suitable employment and judicious medical treatment in diseases of the mind may, under Divine Blessing, render those afflicting maladies, not only manageable, but removed …”

So the Asylum for Persons Deprived of the Use of Their Reason was established in Frankford. Isaac Bonsall, the first Superintendent, his wife Ann, and their three children arrived on March 3, 1817. Bonsall immediately began recording details of daily life. For the next six years, he tracked the weather, functioning of the kitchen, laundry, dairy, and farm, and meticulously noted details about all “members of the family.” The result was a twelve volume Day Book. It included, for example, the observation about a patient who was depressed and wanted to lie down in the woods to die. He talked her out of it. Other entries show that Ann Bonsall was part of the action. For example, she once created a placebo made of bread and allspice for a patient who complained about not getting medicine. Bonsall’s practice of keeping Day Books provided a valuable window into daily life during the early years.

In 1833, Quaker Thomas Story Kirkbride embarked on his long career in asylum management when he became Resident Physician at Friends. The experience prepared him to design and run an ideal asylum as Medical Supervisor for Pennsylvania Hospital’s new Institute for the Insane. Built to Kirkbride’s specifications on 113 acres between 44th and 46th on Market, it was completed in 1841. The design maximized the flow of fresh air and natural light, featuring corridors lined with generous windows, mirroring elements of Friends Asylum. The grounds were spacious and beautiful, promoting an atmosphere of freedom and peace. Therapeutic practices emphasized intellectual pursuits and healthy activities rather than punishing treatments such as bleeding, Bath of Surprise, or cupping. Kirkbride supervised the institute for 43 years and founded of the Association of Medical Supervisors of American Institutions for the Insane, the forerunner of the American Psychiatric Association. His approach to asylum structure and care represented the gold standard during the asylum era.

From the earliest days of Philadelphia, the Society of Friends worked to provide comfort and aid to those experiencing mental illness. They urged the city to step to the forefront, resulting in the first hospital in the North American colonies in the mid-18th century. In 1817, they were first to establish a Quaker retreat in the United State. Kirkbride’s experience at the retreat guided him to become a powerhouse in the new field of asylum science in the mid-19th century. It was clearly Quakers all the way down.

Sources

Bonsall, I. Superintendent’s Daybook. vol. I, 1817-1820. http://triptych.brynmawr.edu/cdm/ref/collection/HC_DigReq/id/15151

Cadbury, H.J. (1948). George Fox’s Book of Miracles. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cheyne, G. (1733). The English Malady; or, A Treatise of Nervous Diseases of All Kinds, as Spleen, Vapours, Lowness of Spirits, Hypochondriacal and Hysterical Distempers. London: Strahan.

Clark, S.P. (1951). Pennsylvania Hospital since May 11, 1751: Two Hundred Years in Philadelphia. The Newcomen Society: New York.

Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh. The Cullen Project: digitizing medical history; accessed (7 Feb. 2018) at: https://www.rcpe.ac.uk/heritage/cullen-project-digitising-medical-history

Tuke, S.H. (1813) Description of the Retreat, an Institution near York, for Insane Persons of the Society of Friends. York: W Alexander.

*Sharlene Walbaum is at Quinnipiac University. She received an F.C. Wood Institute Travel Grant from the College of Physicians of Philadelphia in June 2019.