We have all heard the phrase “an eye for an eye.” The full passage, from The Code of Hammurabi, 2250 B.C.E., reads, “If a man destroy the eye of another man, they shall destroy his eye.” Less well known are the other ocular codes, including, “If a physician open an abscess (in the eye) of a man with a bronze lancet and destroy the man’s eye, they shall cut off his fingers.”

Ophthalmology, in a way, thus existed in ancient Babylon, meaning that the field is over 4,000 years old. Indeed, the ancient Egyptians detailed the treatment of cataracts and trachoma in papyri dating to 1650 B.C.E.

Hippocrates, the father of all medicine who lived in Greece in 5th century B.C.E., knew of the optic nerve, though he did not understand its function. He described many treatments for maladies of the eye, including restricted diets, hot footbaths and even cutting incisions into the scalp to excise the “morbid humors” of the eye. Galen, whose influence on Western medicine through the 18th century cannot be overstated, wrote two volumes related to ophthalmology, both of which are lost to history. However, his Anatomy and Physiology of the Eye exists to this day and prevailed for nearly 1,500 years after his death in 210 C.E.

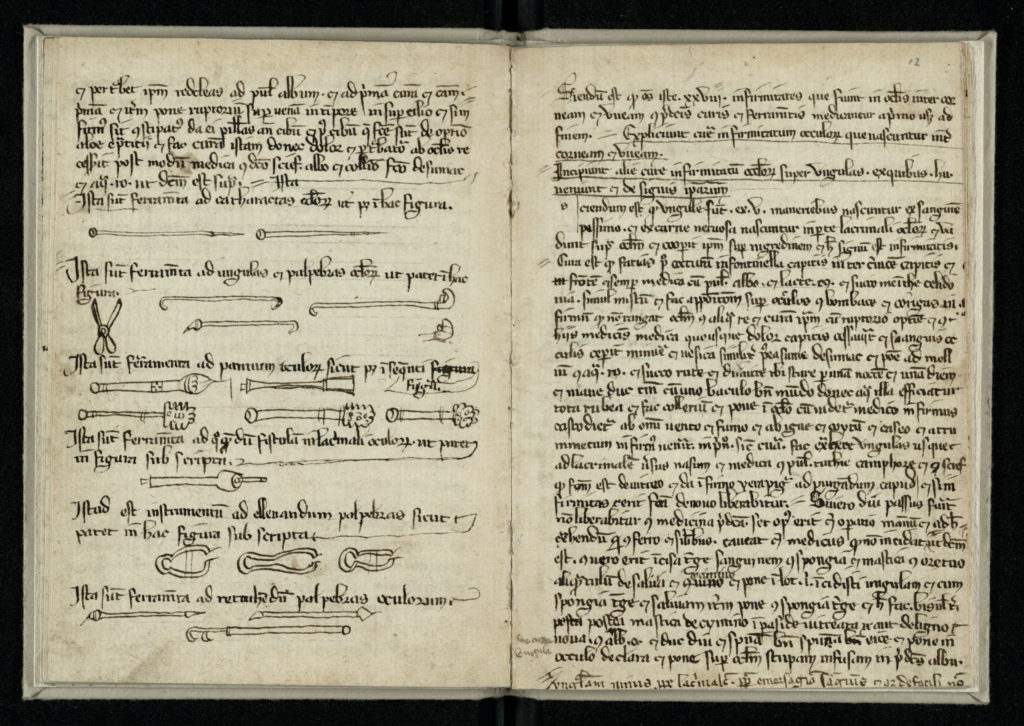

Many of the major ophthalmic discoveries of the Middles Ages belong to the Arabic physicians. Rhazes, born in 850 C.E., first described the reaction of the pupil to light. Ammar Ibn Ali Al-Mosuli, born between 950 and 1000, invented the suction method of cataract removal. Ali Ibn Isa, who lived in Baghdad during the 11th century, was the author of the earliest surviving textbook on the eye, The Memorandum Book for Occulists, which is notable as well for providing the first reference in medical literature to the use of anesthesia in surgery. At the same time, many mathematical discoveries were also occurring in the Arab world, including the first accurate descriptions of light reflection and refraction by Ibn al-Haytham, now considered the father of modern optics.

It was through the translations made by Constantinus Africanus (whose manuscript Viaticum is in the collection of The Historical Medical Library) that many of these works became known in Latin, and therefore available to Western physicians. He even coined the word “cataract,” the meaning of which referred to the contemporary belief that the lens of the eye was filled with a liquid that flowed down into it from above.

The 16th century saw many great leaps. Giacomo Berengario first accurately described the conjunctiva, or the mucous membrane that covers our eyes and the inside of the eyelids. Andreas Vesalius, whose magnum opus De humani corporis fabrica helped advance anatomy beyond the era of Galen (copies of which are also held here at The Historical Medical Library), discovered that the lens of the eye, when removed, acts like a convex lens of glass.

Possibly the greatest contribution of this era, however, was the publication of Ophthalmodouleia das ist Augendienst, by Georg Batisch in 1583. Considered by some the precursor to the modern textbook, it was the first ophthalmic textbook in the German language. In addition to creating this highly influential work, Batisch was also the first optic surgeon to remove completely an eye from a living patient.

Though Fabricius of Aquapadente demonstrated the true position of the eye’s lens behind the pupil around 1600, his discovery was largely disregarded at the time. Michel Brisseau confirmed Fabricius’ discovery in the 18th century, and described it in his 1709 Traité de la cataracte et du glaucoma. Again, this discovery did not make a splash until Maitre-Jan, considered the father of ophthalmology in France, began to energetically support and spread this concept. Around the same time in 1722, St. Yves in France performed the first full removal of a cataract in a living patient.

Though lenses existed in the Egyptian and Mesopotamian worlds, and the Greeks and Romans had theories on light and vision, it was not until the 14th century that lenses were used as spectacles for improving eyesight. Though the first inventor is unknown, the Italian Alexander de Spina re-invented them in 1313, and they were in general use by the middle of the century. It would not be until the 18th century that Benjamin Franklin would invent the bi-focal, and even later in the 19th century, when the fitting of glasses and the measuring of visual acuity would become the domain of the ophthalmologist.

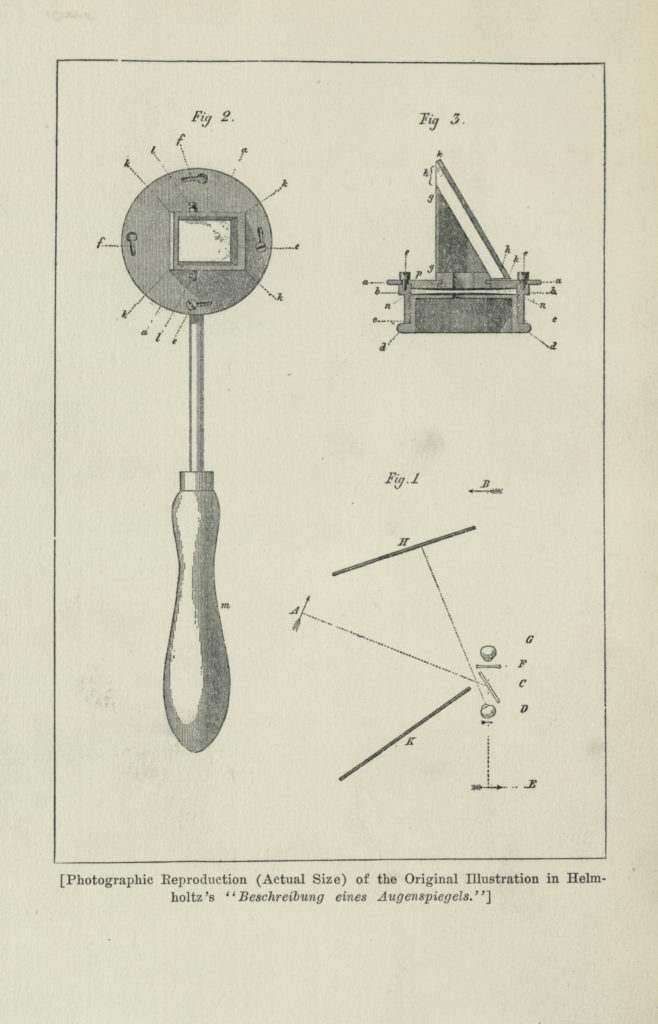

The 19th century saw one of the biggest milestones in the field, the invention of the ophthalmoscope, which allowed physicians for the first time to see into the eyeball in order to diagnose and treat pathological abnormalities. Though the mathematician Charles Babbage independently invented a similar instrument some seven years earlier, credit for this momentous discovery is given to the Hermann von Helmholtz, who published the groundbreaking Description of the Ophthalmoscope in 1851, thus encouraging use of the device to spread rapidly through the medical world. The 19th century also saw the beginning of the professionalization of the field, with the creation of many professional societies and journals.

Since most of the 20th and 21st centuries are out of scope for our collections, this brief history will end here, but stay tuned to our Twitter account, @CPPHistMedLib, where we will be posting “eye-popping” (sorry, I had to) images from our collection related to the history of ophthalmology. As the ophthalmoscope let physicians see into the eye itself, this Twitter series will let you see into various texts and ideas discussed in this post. I hope you enjoy them.

Sources:

Gorin, George. History of Ophthalmology. Publish or Perish Inc., 1982. Historical Medical Library of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, WW 11.1 G669h 1982

Shastid, Thomas H. An Outline History of Ophthalmology. American Optical Company, 1927. Historical Medical Library of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, Kx 4