– by Charlie Dawson, Visitor Services/Gallery Associate

In 1789, King George III of England began experiencing signs of mental distress, including rambling speech, insomnia, and sexually inappropriate behavior. His behavior became so troublesome that doctors would confine the king to a straitjacket for hours at a time. During this period, Parliament considered deposing the ailing king in favor of his son, the prince of Wales. These events would eventually be known as the Regency Crisis.

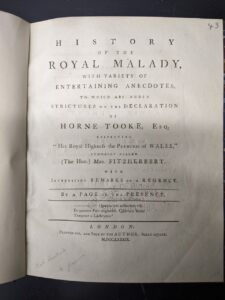

An interesting artifact of this period resides in the Historical Medical Library (HML). It’s a pamphlet written by Philip Withers, a former chaplain and courtier in the household of George III. Its over long title can be summarized History of the Royal Malady. It came to the library thanks to the Fund for Rare Books sometime between 1910 and 1912.

History of the Royal Malady features accounts of conversations supposedly overheard by Withers in the palace. It takes a particular stick to the eye of the prince of Wales, the would-be regent, and his semi-secret wife, Maria Fitzherbert.

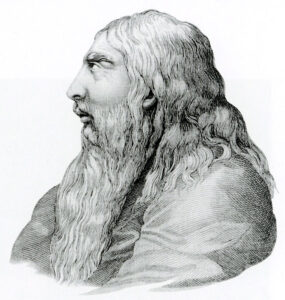

George III was a fairly popular king, give or take the loss of some American colonies. After this loss, the king turned more to domestic affairs and left decisions of state to his prime minister, William Pitt the Younger. The king earned the affectionate nickname “Farmer George” for his interest in the minutia of his agricultural nation. He kept height charts for all fifteen of his children and never took a mistress. In other words, there was a certain Teutonic orderliness that led his court to be nicknamed the “Palace of Piety.”

In such a situation, the king’s son could only respond with extravagance. The prince of Wales was in many ways the quintessential spoiled rich kid – accruing gambling debts, debts to clothiers, continually appealing to Parliament for a raise in his allowance. But he was also known as a quick wit, a talented mimic, and a lively conversationalist in opposition to his somewhat dour father. He also believed, rightly or wrongly, that his father disliked him and had since childhood.

Thus disposed, the prince of Wales started hanging out with Charles Fox, leader of the Whig party that was largely opposed to everything the king did. Like the young prince, Fox liked to party.

We have on one side the Tory party, as represented by Pitt the Younger, advocating the supremacy of the Church of England and the king’s prerogative to do pretty much what he wanted. On the other side, the Whig Party, led by Charles Fox, were standard bearers of Enlightenment-influenced ideas of rule with consent of the governed. These are the broad outlines. In reality, George III cared deeply about a monarchy beholden to its subjects and wrote essays on how to avoid becoming a despot.

When the Regency Crisis arrived, the Whigs advocated that, as the heir to the throne, their creature, the prince of Wales, be automatically named regent. The Tories countered that, sure, the prince of Wales could be named regent, or it could be literally anybody else, and the decision is up to Parliament alone. Here is a seeming reversal, with the Whigs advocating the royal prerogative and the Tories pushing for Parliament’s supremacy.

Now, although George III was a conscientious bridegroom, his brothers were not. They married unsuitable women – Catholics and divorcees and commoners. This led to the Royal Marriage Act of 1772, whereby members of the royal family could marry only with the approval of the king. It was especially important to keep them from marrying Catholics because the 1701 Act of Settlement, which united England and Scotland, barred Catholics from the throne (this included queens). For perspective, it was only in 1778 that the Papist Acts allowed Catholics to buy property and serve in the military.

What’s a young prince to do when he’s run out of middle fingers to hurl at his father? Marry a Catholic widow in secret of course. That’s what the prince of Wales did with one Maria Fitzherbert, which seems to be what raised the hackles of our pamphleteer, the former Anglican chaplain Philip Withers.

Withers describes himself as “Senior Page of the Presence” with rooms adjoining those of the royal family. Much of the pamphlet consists of conversations overheard through latticed spyholes like in a licentious costume drama. Normally, Withers assures us, he wouldn’t listen in on such private conversations, but he has done so for the good of the nation during this crisis of the king’s mental health.

In the first section, Withers relates a story, which he claims to have witness firsthand, wherein the king addresses a tree as though it were the King of Prussia, vigorously shaking the tree’s branches as if it were a person’s hand. Even in delusion, Withers stresses the king’s piety:

“His majesty, though under a momentary dereliction of reason, evinced the most cordial attachment to freedom and the protestant faith.”

Withers relates another story where the king is riding in a coach with his daughters when he turns to the Princess Charlotte, and says, “Will you give me leave to *******?” with the implication of masturbation. Later, our pamphleteer is himself attacked when he is slow to answer the king’s questions. The king grabs Withers by the collar and punches him in the face.

There is something here about the cultural relativism of mental illness. Were a Roman Emperor to behave sexually badly and beat up his servants, would that register as mental illness? But, that era’s expectation of good manner, even on the part of the king, may be the point, as one of the king’s physicians observed:

“If a patient of consummate chastity, like the King, pronounce aloud, what I blush to repeat even in a whisper, we have reason to dread the result.”

It’s the king’s physicians who come in for the worst of it. The king tells his physicians to dance. They decline. The king then thrusts his dinner knife at them and says:

“’Here is my sceptre… and by G-d the man, who presumes to oppose my Will, shall be instantly – instantly impaled alive…’ And then the King called for his Flute… and thus ended the Sabbath day.”

Withers has a good wit if you reduce him to ellipticals.

The most memorable story in Withers’ pamphlet requires some background. A cloaca is a bird’s all-purpose orifice for reproduction and excrement. The Cloaca Maxima was the terminus of the Roman sewer system, overseen by the goddess Cloacina. In George’s day, to worship at the shrine of Cloacina became a euphemism for using the privy.

One day, Withers writes, when “His majesty has lately propitiated the Goddess by a copious sacrifice,” the king gave his physicians a good clock to the face, fetched his overflowing chamber pot, and dumped the contents on the poor physician’s head. This was a knighting of sorts, as the king intoned, “Arise, Sir George, knight of the most antient [sic], most puissant, and most honorable order of Cloacina, Goddess of the Golden Soil.” The king then laughed himself to sleep.

Withers’ account of the king’s derangement makes it far more severe than other sources. Yet his intention was not to paint the king as an invalid and so argue for a regency. It was to depict Charles Fox and Maria Fitzherbert as schemers, taking advantage of the king’s illness to impose themselves into power. If decorum prevents Withers gathering intelligence on this matter, then decorum be damned.

One night, after bidding the royal family good night, Withers writes, “I withdraw to my apartment. Curiosity, however, urged me to the screen, that from a slight aperture I might view her ladyship…The Prince again enfolded her Ladyship and claimed an intercourse of wedded rights. And I withdrew.”

Yet Withers’ recollection of this conversations continues past this withdrawal. The prince mentions that Lady Fitzherbert has been offered a stipend if she will withdraw to a convent. The Lady is adamant that although raised Catholic she is now a practicing Protestant. This is no matter to Withers, who despises her still as a schemer, a conniver, and a *****.

In addition to these conversations, the pamphlet includes one Withers supposedly overheard between the Bishop of Canterbury and someone identified as Lord Cynic. Of the king’s illness, the Bishop says, “The truth is, the King was never greatly burdened with sense, and therefore some slight derangement has overset him.”

This is a pretty sick burn, but Withers’ intention here is to depict the two participants in this conversation as the Bad Guys. You can tell because they say Bad Guy things like, “I am determined to eat, drink, and whore as long as I can,” as well as, ironically in Withers’ telling, “As to the People, we must besiege them with Pamphlets and Inflammatory Hand-bills.”

Withers’ own inflammatory handbill soon landed him in hot water. The pamphlet was supposed to be published by Jared Ridgway, known as a Whig partisan. Although not all partisan publishers were in direct contact with, or in the pay of, the party itself, many of them were. Withers may have thought that Ridgway’s loyalty was to the idea of freedom of the press beyond the particulars of party politics, but, at least in this case, it was not.

In a later pamphlet, Withers tells the story of being summoned to a meeting with Ridgway and the mysterious D., sometimes thought to be Maria Fitzherbert, sometimes the prince of Wales himself. The mysterious D. offers Withers a reward if he will withdraw his pamphlet. Withers refuses and demands their return, but Ridgway refuses.

Without Ridgway’s cooperation, History of the Royal Malady saw very little distribution. The suppressed pamphlet was a available at the author’s house – and nowhere else. However, the story of Withers’ imprisonment for libel was followed closely by Tory newspaper The World. In prison, where Withers wrote [—], his rhetoric grew more pointed. To the prince of Wales, he says, “Your highness has no better claim than a highwayman to the distinctions of a man of honor.”

Withers claims not to mind that the prince of Wales is married to a Catholic, but that parliament does mind very much, and Withers cares what parliament thinks. This is rather unconvincing. Nor is it convincing when he writes, “I hope Parliament will avail themselves of the opportunity of expelling those unworthy members, who affirmed that Her Royal Highness was a *****.”

Though his rhetoric toward the prince of Wales grew more direct, still Withers cannot bring himself to blame the prince more than those who corrupted him. Afterall, “to reproach a man for being an idiot is an insult to Almighty God.”

Withers was fined fifty pounds for libel and sentenced to a year in Newgate prison, but he died before the year was up.

While parliament was arguing who had the authority to appoint a regent, the king recovered. This may be owing to the work of Dr. Wallis, whose slightly more modern approach to mental health was depicted by Ian Holm in The Madness of George III. Or it may be owing simply to the cyclical nature of the condition, which can come and go throughout a person’s life, as it did for George III.

1789 also saw the outbreak of the French Revolution. There is speculation by historians that, if the Regency Crisis occurred a few years later, George III would have been replaced promptly by a regent. Afterall, if France was getting rid of perfectly healthy kings, why would the British tolerate an incapacitated one?

The whole brouhaha permanently stained the reputation of the prince of Wales and Charles Fox, who were seen as taking advantage of the king’s illness in order to seize power for themselves. The prince of Wales stopped being seen in public with Maria Fitzherbert after 1790. He eventually married someone more suitable after his father promised to intercede on behalf of the prince’s debts if he would do so. The prince treated this more suitable bride abominably and periodically took back up with Lady Fitzherbert.

George ruled for another twenty years after the Regency Crisis with some relapses. In 1810 [?] his mental acuity deteriorated to the point where the prince of Wales was declared regent. There is speculation that the king’s final illness was prompted by the death of his beloved daughter, Amelia. The cloistering of the king’s daughters, the way the Queen seemed to respond to her husband’s illness by suffocating her daughters and refusing to allow them to marry, is worthy of a Sophia Coppola investigation itself.

As George’s mental condition grew worse, he went blind due to cataracts. The image of the king’s last few years is a dark one, and a stark reminder of the equality of all mortals under nature. When George III died in 1820], the prince of Wales, though he had been de facto monarch for nearly a decade, officially became George IV.

You have scarcely seen a Wikipedia page so full of condemnation and contempt as that of George IV. In an era of rising republican sentiment, George spent lavishly and ostentatiously. He grew very fat and dependent on laudanum for gout. He was given to flights of fancy like claiming to have disguised himself in order to fight in the Napoleonic wars, although unlike his father, these tales were regarded not as delusions of grandeur but merely as lies.

George IV died without legitimate children. He was succeeded by his brother and eventually his niece, Victoria. By relying so heavily on their ministers, George III and George IV accelerated the monarchy’s transition into a more or less innocuous figurehead, which has allowed it to survive into the present day.

Bibliography

The Badness of King George IV. Directed by Tim Kirby. Flashback Television, 2004.

Catania, Steven, “Brandy Nan and Farmer George: Public Perceptions of Royal Health and the Demystification of English Monarchy During the Long Eighteenth Century.” 2014. Loyola University Chicago, PhD dissertation.

Gronbeck, Bruce E. “Rhetorical invention in the regency crisis pamphlets.” Quarterly Journal of Speech 58.4 (1972): 418-430.

Kass, Joshua. “A Royal Disappointment: The Private Scandals of George IV, 1785–1820.” 2007. Bryn Mawr College, PhD dissertation.

The Madness of King George. Directed by Nicholas Hytner. Film4 Productions and the Samuel Goldwyn Company, 1994.

Robinson, Peter. “Henry Delahay Symonds and James Ridgway’s Conversion from Whig Pamphleteers to Doyens of the Radical Press, 1788–1793.” The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America 108, no. 1 (2014): 61–90.

Withers, Philip. Alfred Or A Narrative of the Daring and Illegal Measures to Suppress a Pamphlet Intituled, Strictures on the Declaration of Horne Tooke, Esq. Respecting” Her Royal Highness the Princess of Wales,” Commonly Called Mrs. Fitzherbert: With Interesting Remarks on a Regency; Proving, on Principles of Law and Common Sense, that a Certain Illustrious Personage is Not Eligible to the Important Trust…. London, 1789.

Withers, Philip. History of the royal malady of George III: with variety of entertaining anecdotes, to which are added strictures on the declaration of Horne Tooke, Esq. respecting “Her Royal Highness the Princess of Wales,” commonly called (The Hon.) Mrs. Fitzherbert. With interesting remarks on a Regency. London, 1789.