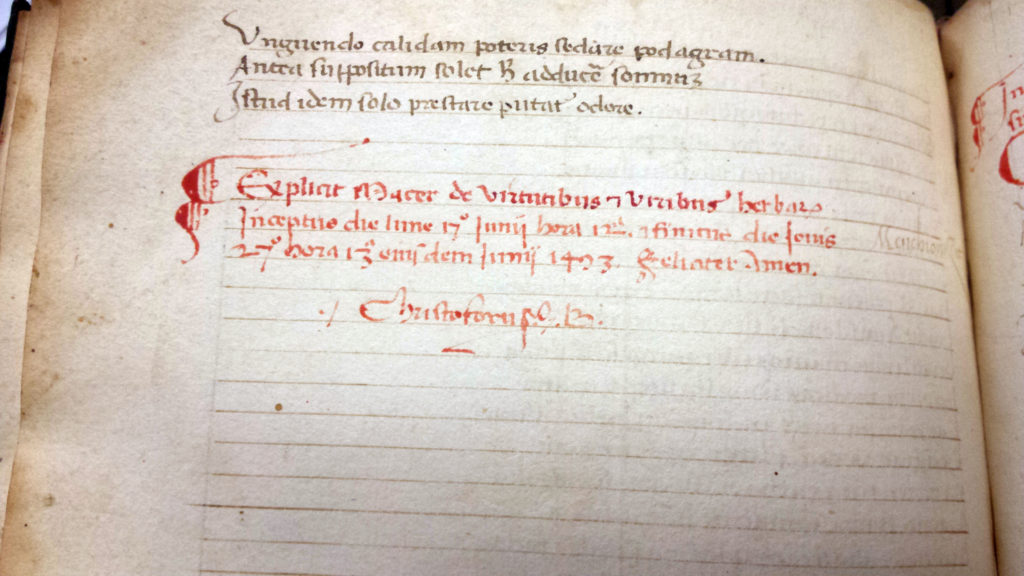

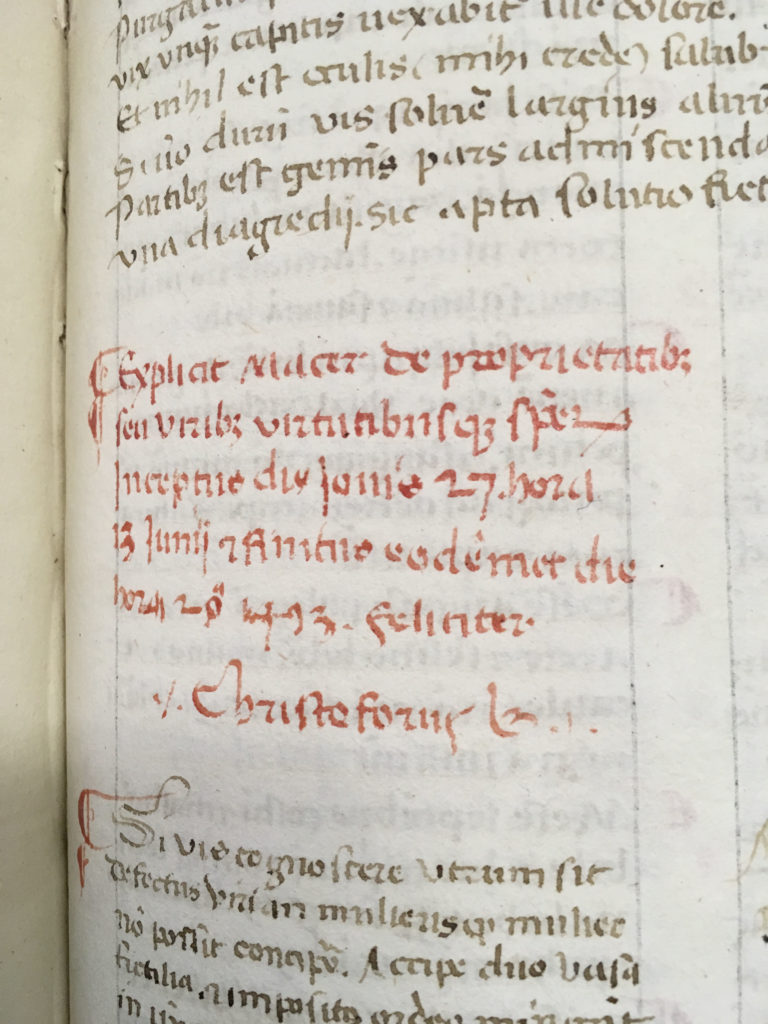

Dating medieval manuscripts can be tricky, as many of them aren’t dated by the scribe, nor do we know who the scribes were. However, 10a 159, Macer Floridus’ De Virtutibus Herbarum, has both a date and a name. We even know approximately how long it took our scribe to complete each section!

Paleography

“Can you give this a look-over?”

Just like modern-day scholars have trouble reading some texts in medieval manuscripts because the handwriting is poor or sloppy; water-damaged, flaking, or torn; in a difficult dialect; or highly abbreviated, so too did medieval scribes. Texts were copied from an exemplar, and it was not uncommon for slight changes to exist among copies from the same manuscript. This could be due to line-skipping, the inability to read a word, or numerous other reasons.

Not an inch of wasted space

Take a close look at line 20. Anything look off to you? While reading semi-gothic cursive script (and in Latin, at that) is not always easy, the last half of line 20 is seemingly completely illegible. That’s because it’s not words at all – the pen-work here is simply to fill in the rest of the line for aesthetic reasons. You’ll also see this kind of pen-work when the scribe tested the flow of ink from the quill.

“The binder ate my homework!”

This manuscript may be the earliest surviving copy of the works included. The works were previously attributed to Arnald of Villanova (and others), but now is thought to have been composed by unnamed people, likely in the area surrounding the University of Montpellier during the early 14th century. The first text relates how to care for (and perhaps cure?) a woman’s infertility, while the second and third texts discuss how to cure diseases of the eye. The texts are written on paper, rather than parchment.

The pages of the manuscript were trimmed at some point. On some pages, the text and not just the margins have been sliced off. Trimming manuscripts was not uncommon, especially if they were rebound in later centuries into ‘more fashionable’ bindings.

Folio 6 verso shows a later reader’s notes – or the original scribe’s demarcations – with the first bits of the phrases cut off.

Making the Medieval Digital

“If [medieval] culture is regarded as a response to the environment then the elements in that environment to which it responded most vigorously were manuscripts.”

– C. S. Lewis, The Discarded Image: An Introduction to Medieval and Renaissance Literature

The Historical Medical Library, as part of the Philadelphia Area Consortium of Special Collections Libraries (PACSCL), is participating in a CLIR grant to digitize Western medieval and early modern manuscripts held by libraries in the greater Philadelphia area. The Library is lending thirteen medical manuscripts dating from c. 1220 to 1600 to this project, called Bibliotheca Philadelphiensis (BiblioPhilly). Our manuscripts will be digitized at the University of Pennsylvania’s Schoenberg Center for Electronic Text and Images (SCETI) and the digital images hosted through the University of Pennyslvania’s OPenn manuscript portal and dark-archived at Lehigh University.