It’s been just over a year since COVID-19 shut down most of the world, including the United States and Philadelphia. The value of libraries and funding them has always been a hot topic, but with libraries shuttering their doors during the early days of the pandemic, it is even more obvious just how much our communities rely on libraries. In my eyes, there is no disputing the value of public and school libraries (see Further reading at the end for some great articles, including one written by Neil Gaiman!) – they do so much more than “just” lending out books.

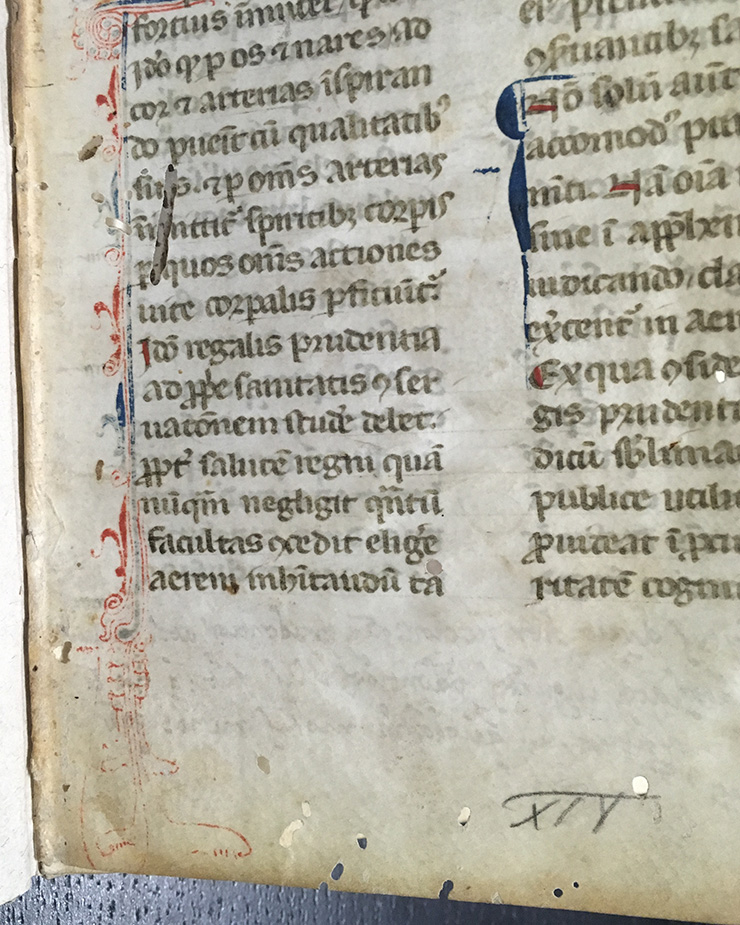

A recent article published in the Philadelphia Inquirer, “Free Library is understaffed, undervalued and budget cuts won’t help”, discusses the issues that many libraries have faced over time: lack of staff, lack of funding, and lack of support. The Free Library of Philadelphia is a valuable resource to all of the neighborhoods and communities it serves, including the scholarly community which makes use of the main branch’s Rare Book Department. The Rare Book Department serves as an example of special collections libraries – which may not be as familiar as public libraries, but face the same problems of lack of resources. So what are special collections libraries?