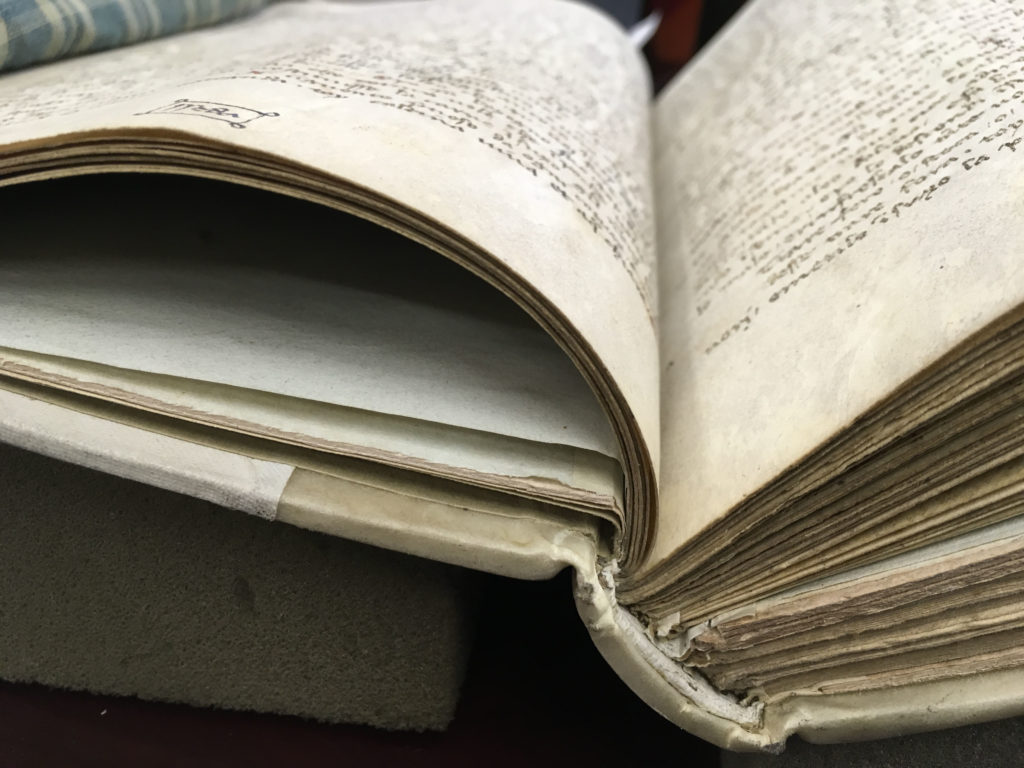

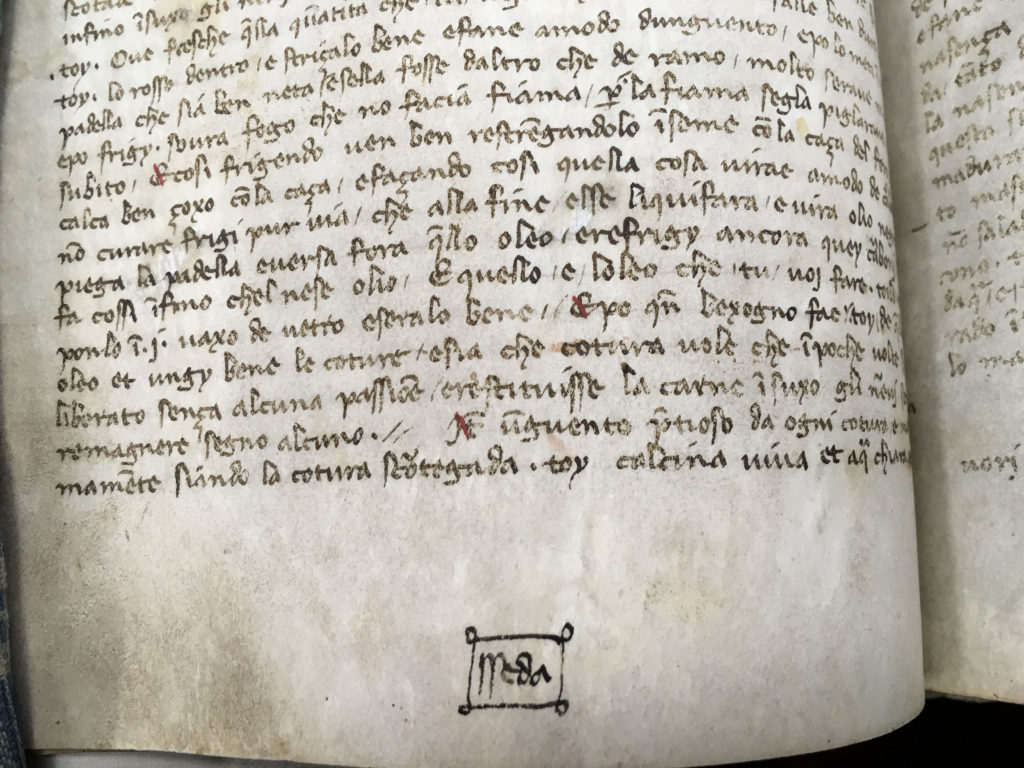

Yes, Virginia, there is such a thing as ‘manuscript waste.’ To us, several hundred years later, it seems a horrible thing. However, it was common practice for early bookbinders to cut up and use pages from unwanted manuscripts as binding material. These pages were sturdy and were used for paste-downs, wrappers (covers), spine-linings, or gathering reinforcements. Not only did the practice essentially recycle texts that were outdated, damaged, or for some other reason, no longer used, it also gives us an opportunity to get a glimpse into the history of a specific text’s use. If we think about it, it’s not too much different than how we treat old newspapers today: as decoupage, potty-training mats for puppies, packing material, etc., etc., etc.

Read more